There can be a democratic, de facto Palestinian state by 2011, according to Salam Fayyad, the Prime Minister of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The goal was outlined in an eloquent two-year plan entitled “Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State,”[1] published in August 2009, which called for the formation of the institutional foundations of statehood prior to, and independent of, an agreement with Israel.

The so-called “August plan” is breathlessly ambitious. It envisions the building of a Palestine International Airport in the Jordan Valley, the reconstruction of Gaza Port, and a passage connecting Hamas’ battered province with the West Bank. Over 20 ministries and ten regional government agencies would be formed and a unified tax and social security system implemented. In places, the plan looks cuddly, promising the planting of five million trees. Elsewhere, it is rather more combative. Much physical infrastructure — as well as a few of the trees, no doubt — is projected for hotly contested West Bank land that Israel shows no sign of surrendering.

The PA’s push for statehood is not only concerned with power lines and labor laws within the Palestinian Territories. It is also taking the PA deeper into key international institutions to drum up international support. In November, Palestinian chief negotiator Saeb Erekat confirmed discussions with United Nations (UN) Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and European Union policy chief Javier Solana regarding a UN Security Council resolution recognizing the independence of Palestine.

Two months earlier, the PA had been in talks with the World Trade Organization (WTO) about the prospect of preliminary membership in the body, which regulates virtually all international trade. In September, former Minister of National Economy Basim Khoury told the UN that the PA “dreams of full accession to the WTO,” which he described as “an engine for reform and an engine of state-building.”[2] The Palestinian Territories could secure “observer” status initially, allowing them to follow developments in trade regulation relevant to Palestinian interests and begin a lengthy process of adjustment to the WTO framework (covering tariffs, duties, rules of origin, product standards, etc.). They could achieve full membership in five years even without statehood (Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao are all members). Khoury discussed the bid with WTO Chief Pascal Lamy, Chair of the WTO General Council Mario Matus, and diplomats from over 50 countries, all of whom supported it.

Israel rejected the WTO bid, as did the US (even though it was the Bush Administration that first promised membership to the PA at a WTO ministerial convention in Hong Kong in 2005). Israel’s response to the WTO bid was indicative of its overall response to the perceived unilateralism of the August plan.[3] “This is contrary to all the agreements signed between the sides,” said Yuval Steinitz, the Finance Minister of Israel’s conservative Likud Party.[4] Steinitz refers in particular to the Oslo agreement — to which the PA owes its existence — which prohibits changing the “status” of the West Bank and Gaza prior to a permanent agreement. “There is no place for unilateralism, no place for threats, and of course, there will be no Palestinian state at all without ensuring Israel’s security,” Steinitz said.

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s response was similar: “Any unilateral path will only unravel the framework of agreements between us and will only bring unilateral steps from Israel’s side.”[5] Dan Diker and Pinhas Inbari, senior foreign policy analysts at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, offered a similarly ominous prediction: “The Fayyad plan would transform the diplomatic paradigm between the PA and the State of Israel from a legally-sanctioned, negotiated process to a unilateral Palestinian initiative that has far-reaching and even troubling legal, political, and security implications for Israel.”[6]

Such responses appear to miss the point. The “legally sanctioned, negotiated process” constructed in the Oslo Accords is not delivering anything meaningful to the Palestinians — the deadline set for the peace process at Oslo passed over a decade ago. But how reasonable is Israel’s defensive reaction to the perceived “unilateralism” of the current PA strategy? On close inspection, the Palestinian push for statehood, and “Fayyadism”[7] more generally, are encouragingly benign.

Take the WTO bid for example. While not an explicit part of the August plan, it is indicative of the PA’s current strategy. At the practical level, preliminary membership in the WTO would strengthen the capacity of Palestinian bureaucrats, thereby enhancing the PA’s capacity to govern. And since WTO membership creates a legally stable trade framework — because disputes between members are resolved within the WTO itself — membership might encourage investment in the region, which is sorely needed. In Gaza 57% of those in the 20-24-year-old age bracket are out of work. In the West Bank, the figure is 29%, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

At the symbolic level, the benefits of a WTO relationship, even a preliminary one, are more numerous. First, the WTO bid shows that the PA envisions Palestine as a free market economy integrated into a Geneva-based institution. Other Arab nations in the WTO (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan) have comparatively stable relations with Western countries and Israel compared to the likes of Iran, WTO outsiders. Saudi Arabia had to drop boycotts on some Israeli goods as a condition for achieving membership, and was restricted from boycotting Danish goods during the Muhammad “cartoon” controversies. With Israel’s trade relations under increasing pressure from an international boycott movement (albeit mostly at the civil society level) the WTO offers important protection.

The ability to pursue diplomatic relationships with institutions like the WTO, and of course the UN, also sends a message to the Palestinians that the PA can operate autonomously at the international level. This perception is crucial if popular support for the PA’s diplomatic track, so ardently upheld by Mahmud ‘Abbas, is to be maintained with so little to show for it. The Palestinians lack trust in Israel as a serious negotiating partner, so diplomacy needs to be conducted on numerous fronts if it is to be meaningful; and institutional relationships are a part of that multi-pronged effort. And importantly, the WTO bid, like Fayyadism generally, shows Israel that the PA is forward-looking, focused on state-building rather than only seeking redress for past wrongs. “This (WTO bid) would send a clear message to the Israelis that a two state solution is considered viable,”[8] said Saeb Bamya to Al Jazeera.

While the August plan covers much of the institutional apparatus necessary for state-building, the nuts and bolts of economic development appear to be of paramount importance. The WTO bid is a part of that, but so are infrastructure, labor laws, and regional integration, which are all given priority. Fayyad — himself a US-trained economist — sees economic growth at the heart of his “build it first” strategy. And to the PA’s credit, the West Bank economy has shown signs of economic revival. This is largely due to the improved security situation, as PA security forces cracked down on Hamas after the 2006 post-election clashes. But in addition to improved security, Israel has moderately relieved some checkpoints as part of a wider policy of “economic peace” whereby improving security is continually met by the loosening of military checkpoints, which further frees up the movement of labor and goods, generating employment and giving the Palestinians a stake in peace.

Such a virtuous circle sounds intuitive, but can the process be sustained? This Policy Brief takes a closer look at the West Bank economy in order to explore that question.[9] It presents the major shifts over recent months in terms of the checkpoints, partly in conversation with Palestinian business people from a variety of sectors, to see if changes are being felt on the ground and whether they can be sustained. Then, the report looks at the Hamas-Fatah split, discussing some of the ways in which that division hinders economic growth. Finally, the report outlines the ultimate bankruptcy of economic peace as a workable idea in light of the geographical constraints of the West Bank.

Recent Shifts in the West Bank Economy

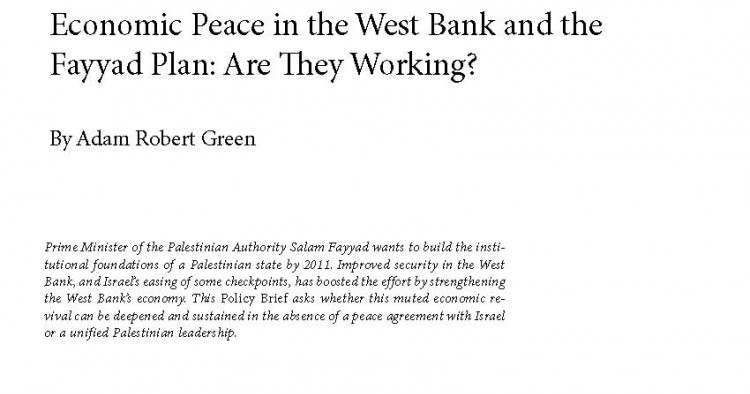

The Palestinians have few (and, with the zigzagging incursions of the security wall, ever-declining) natural resources and in terms of exports, depend largely on the sale of relatively low value goods and services to Israel, its dominant trading partner. The private sector, composition of which is shown in Figure 1, comprises services (tourism and finance), commerce (restaurants and hotels), transport, storage and communications, agriculture and foodstuffs (including flowers, olives, citrus, vegetables, beef, and dairy products), construction and some industrial output (ceramics, marble, stone and cement).

Figure 1

Source: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, http://www.pcbs.gov.ps

Since the Second (al-Aqsa) Intifada in 2000, the West Bank has seen the installation of several hundred military checkpoints, intended to block the entry of suicide bombers into Israeli towns and cities.[10] From a security standpoint, the checkpoints have been successful. Violent acts against Israeli citizens, conducted from the West Bank, have dropped remarkably. Yet problematically, the presence of Jewish settlements in the West Bank (that is to say, on land exceeding the 1967 borders) means that most checkpoints actually exist within the West Bank itself, rather than around it.

This had the effect of disrupting the movement of Palestinians within the West Bank. For goods-trading businesses to pass checkpoints, products, often stored in wooden pallets, are transferred to an Israeli vehicle by forklift truck before undergoing manual, electronic, and sometimes canine inspection. Truckloads can take anything from 20 minutes to four hours to pass through each checkpoint, and many have to pass several per day, raising per-kilometer labor costs by anything from 34% (the Hebron-Jenin route average) to 78% (the Ramallah-Jerusalem route average).[11] According to a World Bank study in 2008, checkpoint-related delays can raise transport times on the Ramallah-Jerusalem route by up to 366%.[12]

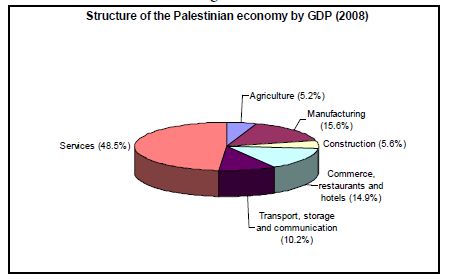

Figure 2

Source: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, http://www.pcbs.gov.ps

“The checkpoints are a disaster for our beer business,” says Nadim Khoury, managing director of Taybeh Brewing Co., a Palestinian brewery based in Ramallah. “Our beer is a natural, high quality beer, and cannot face six to eight hours under the sunlight and heat. Sometimes we return to the brewery rather than wait, and sometimes we are forced to stay because if we decide to go back the soldiers will shoot at us thinking we have something suspicious in our trucks.”[13] Uncertainties about waiting times at checkpoints and their opening hours, flying checkpoints, and non-transparent and unpredictable changes in the permit systems all negatively impact labor mobility, says Martin Oelz, Legal Officer at the International Labor Organization (ILO).[14]

A company’s working day is limited by the hours during which the checkpoints are open. Nassar Stone Investment Company — a stone and marble producer that exports to the US, Europe, and Asia — only can gain access to some of its quarries during certain times, a fate it shares with other Palestinian producers such as Suhail & Saheb for Stone & Marble Ltd. and Al-Anan Company for Marble & Stone.

Following the split between Hamas and Fatah after the 2006 elections, the latter were able to crack down on militants in the West Bank, leading to a period of peace. “Improved security is one of the best things that ever happened to any private business, and Fayyad should be proud of this,” said Ammar Aker, CEO of Palestine Cellular Communications Co. Ltd., or Jawwal, the main Palestinian mobile telecom company.[15] “Better internal security throughout the West Bank means people are going out more, and spending more,” says Bashar Masri, a Palestinian entrepreneur with businesses spanning financial services, IT, and real estate, who noted that areas like Nablus are in a relative boom.[16]

Binyamin Netanyahu responded to the improved security with talk of an “economic peace” whereby Israel “would lend growth to the moderate parts of the Palestinian economy,” as outlined in his foreign policy speech to the nation in June 2009. This has seen checkpoint opening times extended at Nablus, Ramallah, Qalqiliya, and Jericho, with some checkpoints decommissioned. For Masri, journeys between Nablus and Ramallah now usually take around 45 minutes instead of the previous four hours. In Nablus, trade has improved, according to Omar Hashem of the Nablus Chamber of Commerce.[17] In Ramallah, tourism is on the rise, and two new hotels are under construction. This fragile improvement has been noted by Palestinians that had emigrated elsewhere. Bashar Masri says he has recently been able to employ émigrés, despite their falling pay. “In the Gulf, they earned $10,000 a month. Here they earn $3,000-$5,000. But they are home.”

Masri goes on to say, though, that the shift is both limited and reversible. Some of the checkpoints decommissioned as part of the “economic peace” plan, for instance, are still manned by soldiers: “The structures have come down, but often there are soldiers by the road sides. This gives you a feeling they are still here, so it’s a very shaky opening. And as a businessman, this uncertainty is a problem.”

Many other areas have felt no benefits from the checkpoint relief. In Jenin, checkpoint improvements have not served to increase trade volume, according to Talal Jarrar of the Jenin Chamber of Commerce.[18] Hebron has shown no economic growth, according to Maher al-Haymoni, director of the Hebron Chamber of Commerce.[19] And there has been no overall increase in jobs over the last year anywhere in the region, according to the ILO’s Oelz.[20]

Israel also has been slow to make technical improvements in existing checkpoints which could minimize their obstruction to daily life, especially for trading companies. Cooling facilities to protect perishable goods, such as Taybeh’s beers, could be installed at checkpoints, but there are no such facilities at West Bank commercial crossings or at the Allenby Bridge. Israel’s justification is that there is no need for cooling facilities since goods should be processed during an average time of 45 minutes, according to Ranan al-Muthaffar, Private Sector Specialist at the World Bank.[21] Israel also has been advised to invest in more laser and X-ray scanning technologies so that goods such as furniture and glass can be checked in situ because they are frequently damaged when unloaded for inspection, according to Salah Awdi, Director-General of the Ramallah-al-Bireh Chamber of Commerce. Moreover, trucks cannot always travel at full capacity.[22] Nassar Stone Investment Company, for instance, has to leave space in its container vehicles to allow access to sniffer dogs, reducing the quantity of cargo it can transport per trip.

There is one scanner at each West Bank commercial crossing but better scanning technologies would allow companies to transport more goods per trip. Nadim Khoury at Taybeh Brewery can only export through Tarquima checkpoint — not the nearest — because it is the only one with lasers capable of scanning the inside of the stainless steel kegs in which the beer is stored, creating a detour which significantly lengthens his journey. At Allenby, a new scanner was installed in April 2008. Though it is larger than the previous scanner, it is still built to scan pallets and thus cannot scan trucks.

Finally, an accessible online or telephone service informing Palestinians of any relevant changes to checkpoints could be made available in order to alleviate trading uncertainty. However, Israel is not prepared to make available such information “for security reasons,” according to Al-Muthaffar at the World Bank — though it is not clear what the risks are.[23]

So the improvement to the checkpoints is fragile and limited. Many existing checkpoints could be greatly improved. Of course, the improvements that have occurred should be recognized. The combination of improved security and economic peace has generated, as Masri said, “a relative boom” in towns like Nablus. The question is, can it be deepened and sustained? Here, the prospects look bleak. The proper liberation of the Palestinian economy requires a continuous decommissioning of checkpoints in response to ever-improving security. But Israel is committed to controlling “Area C”[24] (the land mass covering the settlements, the Jordan Valley, and the high ground around Jerusalem and overlooking Israeli cities along the Mediterranean coast). This drastically limits the sustainability of “economic peace” because a large number of core checkpoints that directly protect settlements are unlikely to be considered for decommissioning. Once the low-hanging fruit is picked (e.g., lengthening opening times), economic peace will reach its limit — Israel will not remove the military protection of its actual settlements and towns (which are growing in number). And even if the decommissioning goes further than we might think, it takes just a single attack for an overnight reversal, or even an escalation. The PA forces are adept, but not superhuman.

What does this mean for the Palestinian economy? Modest improvements have benefited small-scale trading activities, as well as tourism in the larger towns and boosted local markets. But for significant growth in the Palestinian economy, large companies and large enterprises, such as infrastructure and public works, need to emerge. And the ambiguous status of Area C is profoundly undermining such a process. Two examples are illustrative.

Bashar Masri is spearheading a major real estate project, a new town called Rawabi, nine kilometers from Ramallah. Rawabi will house 50,000 people and has secured $500 million in funding from the Qatari sovereign wealth fund. “This is the largest project undertaken in Palestine’s history,” says Masri. But Rawabi — which is to be built from scratch — needs a road connecting it to Ramallah, a key selling point to the properties there, and that road crosses Area C land. Eighteen months ago, Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak agreed to let Masri begin the planning. “We received all the necessary approvals, environmental, geological and the rest. But until today, we still have no final word from Israel about it. We lobby, through the PA, and we’ve been promised it will happen, but for six months — nothing.” The delay is preventing 1,600 new jobs, he estimates. “We could be at the height of construction now.”[25]

Ammer Akker of Jawwal faces similar infrastructure constraints. Jawwal cannot build communications towers — vital to securing network coverage — on Area C land. This means Jawwal cannot provide mobile phone coverage to many major roads such as those connecting Ramallah, Nablus, Jericho, and Hebron, on which thousands of Palestinians travel. Also, because of import restrictions on certain technologies imposed by the Israeli authorities in 2005, Jawwal’s switchers — the main orchestrating infrastructure of mobile network providers — are located on another continent (in London). Such constraints ultimately restrict the growth of the Palestinian economy, since economic “takeoff” depends very much on the emergence of large-scale infrastructure projects and big companies. At present, 90% of Palestinian industrial companies have an average of four employees, according to Medibtikar, an EU research group.[26] Unable to exploit economies of scope or scale, such enterprises have little hope of competing internationally. A nation does not need to be large to grow rich — take Singapore, for example — but it certainly needs to know what its territory is before it can hold its own in a fiercely competitive global economy. Large companies play a big role in the development of exports, and they are struggling to emerge in the Palestinian Territories.

The Palestinian Leadership

Economic development in the West Bank is not only constrained by Israel’s military presence. The Hamas-Fatah divide also undermines economic development. The split also deepened after the December 2008-January 2009 conflict in Gaza, with Hamas claiming that Fatah had provided intelligence to the Israeli Defence Force (IDF). The parties’ dispute prevents the Palestinian government speaking with one voice on even the most basic political goals — such as whether to recognize Israel, or to endorse armed resistance — let alone the intricacies of economic policy. It also entrenches the economic separation of the West Bank and Gaza, fragmenting an already small Palestinian market.

In October, Egypt brought Hamas and Fatah together to work towards a hybrid government, one of several such attempts over the course of 2009. But while both sides claim to desire Palestinian unity, a workable arrangement seems as distant now as it was when power-sharing discussions began in the early 1990s (and Egypt is hardly the appropriate negotiator, given Hamas’ relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood, the leading opposition force in Egypt). More worryingly, if power-sharing is successful, it will likely undermine the recent progress in the West Bank. Hamas wants to return there, inevitably provoking the reinforcement of checkpoints and jeopardizing trade between the West Bank and Israel (which increased 17% in 2008).[27] Hamas wants representation in the security forces, crushing any hope of a hand-over of security in the West Bank from Israeli to US-trained PA security forces. And most problematically, Western donors may cease their aid to the PA if Hamas is formally incorporated. Such a move would be disastrous for the entire Palestinian economy, including in the West Bank, which is still largely aid-dependent.

Besides the negative impact that Hamas could have on economic development were it to form part of the Palestinian government, there is also the issue of whether Hamas and Fatah would be able to devise a unified economic policy. This looks unlikely. “Hamas want to build trade links with the Arab and Islamic world and de-link the Palestinian and Israeli economies,”[28] argues Nathan Brown, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at George Washington University. Such trade discrimination would be impracticable in the WTO framework that the Fatah PA favors (the WTO’s raison d’être is to act against trade discrimination). Hamas also might oppose formal trade relations with Husni Mubarak’s Egypt given the bitter relationship that currently exists between the two. Iran’s failure to join the WTO, the wider trade sanctions it faces in regards to the West, and its increasingly geopolitical as opposed to economic trade strategy, is also relevant given its relationship with Hamas.

Hamas has not advanced any sophisticated framework for the Palestinian economy,[29] but it is clear that what signals have been made are quite different to those of Fayyad and his associates. The direction that “Palestine” might take in terms of its trade policy (i.e., open and WTO-compliant or parochial and pan-Arab) will completely shift how the economy functions and where foreign investment will come from. Therefore those wishing to invest in major projects in Palestine, especially international investors, are unlikely to move until the Palestinian leadership is established and the future strategy becomes apparent. And while such investment waits, development stalls. “Without a basic formula for unity between the West Bank PA and Hamas, there is little chance for sustainable Palestinian economic development,”[30] says Haim Malka, Deputy Director of the Middle East Program at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Professor Brown does not believe that the Hamas-Fatah division will be permanent. He said: “The ethos of national identity among inhabitants of the Palestinian territories remains extremely strong and no political arrangements enshrining the division will be accepted as legitimate.” But Brown admits there is “no realistic path toward healing the rift any time soon.”[31]

The coming year will be decisive in defining how the division evolves. Elections for the leadership of the PA are planned for 2010, probably in the summer. But there remains much confusion about whether the election will take place and who will stand. Hamas has not committed to take part, after their last electoral victory was quashed by Fatah. ‘Abbas recently ruled himself out of contention, exasperated by Israel’s intransigence and the failure of the US to act. “It’s time for you to find another donkey,” he said.[32]

Should the election take place, polls so far have indicated that Fatah would come out on top. A June 2009 poll by the Palestinian Jerusalem Media and Communications Center, and spanning both the West Bank and Gaza, found support for Hamas dropped steeply following the ruination of Gaza.[33] Over 23% of respondents thought Hamas responsible for the failure of dialogue, against 15.5% who blame Fatah (the majority, 26.5%, blame Israel). In September 2009, a survey carried out by pollsters Charney and the International Peace Institute (IPI) gave Fatah 45% of the parliamentary vote and 24% to Hamas.[34]

However, this is a more fragile lead than it appears. In a head-to-head election, ‘Abbas would have defeated head of the discharged government Isma‘il Haniyya by just 52%. And since that poll, ‘Abbas has faced much criticism following his delay of a vote over the UN Goldstone report. Fayyad, meanwhile, was never even voted for (although he’s on something of a campaign trail at the moment). It also should be noted that Fatah itself is suffering profound divisions, making the confusion over the Palestinian leadership yet more acute.[35]

Along with the fragility of this lead, wider trends since those polls are harming Fatah. Israel’s continuation of ‘business as usual’ in regards to the settlements is particularly damaging. Israel persistently refused to freeze settlement expansion as a precondition for the resumption of peace talks. It also failed to crack down on the construction of new settlements that were illegal under Israeli law, or to curb the activities of extremist settlers who have taken to sawing down Palestinian olive trees and attacking mosques. Eventually, Netanyahu announced a ten-month settlement freeze, but it did not apply to East Jerusalem or to building work already underway in the West Bank. Moreover, all building work would resume after ten months even if productive talks were underway.[36] For Palestinians to support a diplomatic engagement with such a partner would be nothing short of miraculous. This plays perfectly into the hands of Hamas. Indeed, some analysts opine that Hamas is content to lay low and postpone elections for the time being in the knowledge that Israel is effectively destroying ‘Abbas and the diplomatic track, lending strength to Hamas.[37] Adept at running local hospitals and charitable organizations, and poor compared with many of Fatah’s wealthier leaders, Hamas has a profound emotional appeal for Palestinians confronting Israel’s intransigence and the inability of the international community to assist them. Support for Hamas actually has increased among some West Bank Palestinians who see them as continuing the resistance, despite the events in Gaza.[38]

So an election, if held, could deliver results for Hamas. There are certainly situational parallels with the conditions preceding Hamas’ 2006 victory; namely, a perception among Palestinians that Israel’s “peace process” is basically a smokescreen, a mirage intended to make the Palestinians look unwilling to negotiate by offering interim gestures that Israel knows the PA cannot accept (such as a partial settlement freeze in this instance).

The one markedly different factor now as opposed to 2006 is, it was hoped, the presence of a new US administration that actively courted the Arab world and that appeared to strongly endorse a Palestinian state. But President Barack Obama, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and Middle East envoy George Mitchell — despite much initial hope and fanfare — have been powerless to comprehensively freeze settlements, instead achieving only the ten-month, partial pause.

“We were hopeful when the Obama Administration started,” said Akker of Jawwal. “Unfortunately this hope is evaporating because of the pressure being put on the Palestinian side and not on the Israeli side. Look at how long the settlement freeze is taking. If the US is not willing to pressure Israel on something minor like freezing settlements, before we even get to big issues like Jerusalem, return of refugees, withdrawal of Israeli troops from the West Bank and so on, then people will lose hope.” Settlements certainly look to be the primary issue for the Palestinians at present. In the IPI poll, a plurality of Palestinian respondents (28%) said the evacuation of Israeli settlements and outposts constitutes the “primary confidence-building shift” in the peace process.

That frustration could in turn lead to a new intifada. Such talk reached a particularly shrill pitch following settler violence on mosques in East Jerusalem, Palestine’s intended capital, last September. Bassam Abu Sharif, a former ‘Arafat aide, claimed at a September press conference in Ramallah that “the Palestinians are preparing themselves for an intifada.”[39] Professor Moshe Maoz of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University said: “another intifada is quite possible.”[40]

Such a prospect is of grave concern to some. Akker at Jawwal said: “I hope, as a businessperson, that this loss of hope will not lead to a return to intifada.” Bashar Masri expressed similar concern. Both figures are major players in the Palestinian private sector, and recognise that a new intifada would undo the small but not insignificant gains of recent months.

In essence, both figures are adopting a Fayyadist approach (i.e. seeking to build their businesses under the confines of the occupation, rather than overturning the occupation as a precursor to building business). They not only see this as a practical approach. They and others also feel an immediate sense of nation-building. Nadim Khoury at Taybeh Brewery said: “We are staying. We want Palestinians to be proud of their country’s products.” Akker said Jawwal is a source of great pride among Palestinians. Operating under great constraints, it has taken an 80% market share from Israel since the late 1990s, and has 900 direct employees, with 30,000 jobs in the Palestinian supply chain. With an average employee age of 29 years old, Jawwal is building a new Palestinian generation, according to Akker. “We hope to make a change in the Palestinian economy and prove to everyone that we deserve to live as a normal society,” he said. When asked how he continues to motivate himself in the midst of a frozen peace process, Bashar Masri said: “It is the duty of every Palestinian to put up with the frustration and build the nation we have always dreamed of building.”

Concluding Remarks

The West Bank economy has benefited from peace on the streets, which encourages economic participation and business confidence. The checkpoint thaw which followed has loosened the noose on daily life to some degree, and that is good for the functioning of the economy, not to mention the dignity of the West Bank’s inhabitants. Combined, these developments have provided a fragile aperture eagerly seized upon by entrepreneurial Palestinians able to maintain and even grow companies under still severe duress. And the potential for foreign investment from the Arab world, which has long rallied around Palestine as a central unifying issue, is worth noting. Masri suggests there is significant funding “waiting on the sidelines” in the Gulf, the Arab world, the West, and the liberal Jewish community, which could transform the economy once there is a wide perception that the Palestinians are the masters of their own fate, in terms of both governance and geography.

As a first step to such autonomy, the challenge now is to turn a short-term period of growth into sustained economic development, which brings jobs and opportunities. That would require an economic peace that could escalate continuously, until the Palestinian economy can function with substantial (if not total) freedom (even allowing for a hard separation between a future Palestine and Israel). In theory, such an arrangement is entirely possible, but in practical terms it is difficult to see how it would work in light of Area C. What the Palestinian economy needs is major infrastructure spanning communications, power, and transport; the emergence of large companies that can compete internationally; and large-scale construction projects that bring jobs and fuel urbanization, which has well-established “agglomeration” effects. But large companies and large-scale projects soon enough set foot on contested land, as we have seen in the case of Rawabi and Jawwal. So the checkpoint thaw might improve personal life, and even improve commercial life for small companies, but it offers little to the bigger players on whose shoulders major development depends. Even if Israel decided to go further in its decommissioning effort, a single act of violence would likely see a reversal. And such violence is made all the more likely by Israel’s baffling approach to settlement expansion.

Indeed, while the right of return for refugees, the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the West Bank, and the Hamas-Fatah leadership rift are all important issues seeking resolution, the expansion of the settlements is the foremost threat to the peace process at the current time, making a mockery of Fayyadism and undermining the PA’s significant achievements in improving security and pursuing the institutions of statehood. Between now and the summer of 2010 — and, it should be noted, the end of the settlement “freeze” — the institution-building approach will come under strain. If Israel does not shift its position on the settlements and make economic peace begin to look like a sustainable prospect — or if the US cannot find a way of influencing Israel along such lines — “Fayyadism” will prove increasingly difficult to sustain.

[1]. Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State, Palestinian National Authority, August 2009, www.miftah.org/Doc/Reports/2009/PNA_EndingTheOccupation.pdf.

[2]. “Palestinians want support for WTO observer status bid,” Agence-France Presse, September 22, 2008.

[3]. Criticisms also were issued by Palestinians. Asked about the Fayyadist strategy, Dr. Adel Zagha, Vice President of the Office of Planning, Development and Quality Assurance at Birzeit University near Ramallah, said: “When a nation has no control over its territorial borders, no contiguity among its regions, where it faces military closures for security reasons and while it lacks national unity, development plans are nothing more than an exercise to solicit funding.” Interview with author, October 14, 2009.

[4]. “Palestinian Leader Maps Out Plan for Workings of Independent State,” The New York Times, August 26, 2009.

[5]. “Netanyahu: If Palestinians act unilaterally, so will Israel,” Haaretz, November 25, 2009.

[6]. Dan Diker and Pinhas Inbari,“Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s Two-Year Path to Palestinian Statehood: Implications for the Palestinian Authority and Israel,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, October 2, 2009, http://www.jcpa.org/JCPA/Templates/ShowPage.asp?DBID=1&LNGID=1&TMID=111….

[7]. The term is Thomas Friedman’s, referring to “the simple but all too rare notion that an Arab leader’s legitimacy should be based not on slogans or rejectionism or personality cults or security services, but on delivering transparent, accountable administration services ... [Fayyad] is an ardent Palestinian nationalist, but his whole strategy is to say: the more we build our state with quality institutions — finance, police, social services — the sooner we will secure our right to independence.” See Thomas Friedman, “Green Shoots in Palestine,” The New York Times, August 4, 2009.

[8]. Alexander Sehmer, “Palestinians eye role on trade body,” Al Jazeera, September 21, 2009, http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/2009/09/200992014841509800….

[9]. The West Bank is the exclusive focus of this report because the Gaza economy is not functioning in any real sense, and the relationship between the Palestinians and Israel is likely to emerge from that which can be built between the West Bank PA and Israel, making the PA model the most logical one to scrutinise.

[10]. Many of the suicide bombers active during the Intifada came from West Bank towns such as Nablus. The security wall is also of significant importance to the Palestinian economy, since it has caused the loss of fertile arable land and limited the movement of Palestinians into and out of Israel. However, this report intends to focus on the checkpoints because they are more disruptive for trade within the territories and also more amenable to decommissioning, as will be discussed.

[11]. Palestine Trade (PALTRADE) Centre Data 2009, http://www.paltrade.org/en/.

[12]. World Bank, West Bank and Gaza, Palestinian Trade: West Bank Routes, December 16, 2008, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWESTBANKGAZA/Resources/PalTradeWB….

[13]. Interview with author, October 28, 2009.

[14]. Interview with author, November 3, 2009.

[15]. Interview with author, November 1, 2009.

[16]. Interview with author, November 8, 2009.

[17]. “Trade revives as Palestinian cities reconnect,” The Independent, August 27, 2009.

[18]. “Trade revives as Palestinian cities reconnect.”

[19]. “Trade revives as Palestinian cities reconnect.”

[20]. Interview with author, October 2, 2009.

[21]. Interview with author, October 14, 2009.

[22]. “Palestinian-Israeli trade looks up,” Asia Times Online, September 10, 2009.

[23]. For an excellent report on other technical improvements that could be made to checkpoints, see “Report on Palestinian Movement and Access,” University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, http://igcc.ucsd.edu/pdf/M&A%20Report%20Final%20-%20April%2015.pdf.

[24]. Netanyahu is committed to Area C for two reasons: He wants a militarily stronger border than that of 1967, and he is committed to the existence and, apparently, expansion of the settlements.

[25]. Interview with author, November 7, 2009.

[26]. General economic profile: Palestine Authority, Medibtikar Project, http://www.medibtikar.eu/1-1-General-economic-profile.html.

[27]. Trade between Israel and the PA rose 17% to $3.9 billion in 2008, according to the Israeli Tax Authority (ITA). In 2007, it was $3.3 billion, and in 2006, $3 billion.

[28]. Interview with author, October 12, 2009.

[29]. Interview with author, October 14, 2009.

[30]. Interview with author, October 2, 2009.

[31]. Interview with author, October 2, 2009. The internal conflict is called waksah among Palestinians, meaning “humiliation.”

[32]. “In a Warning to Obama, Abbas Quits Election,” Time, November 6, 2009.

[33].A public opinion poll conducted by Jerusalem Media & Communications Center, June 2009, http://www.miftah.org/Doc/Polls/PollNo68JMCC.pdf.

[34]. “Palestinians want peace deal but don’t reject Hamas,” Reuters, September 25, 2009.

[35]. Helen Cobban, “Who Speaks For the Palestinians at the Negotiating Table?” Middle East Institute Podcast, September 24, 2009.

[36]. “Israel warns on resuming settlement activity,” Financial Times, December 6 2009.

[37]. Omran al-Risheq, “Where is Hamas in the West Bank?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November, 2009, http://www.carnegieendowment.org/arb/?fa=show&article=24120.

[38]. Al-Risheq, “Where is Hamas in the West Bank?” http://www.carnegieendowment.org/arb/?fa=show&article=24120.

[39]. “Former Arafat aide: Third Intifada on its way,” Ma’an News Agency, September 29, 2009.

[40]. “Riots in Jerusalem as Israeli forces storm mosque may point to third Palestinian uprising,” Palestine News Network, October 1, 2009.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.