Originally posted June 2011

Jeanette and I walked into the Executive Leadership Center at Morehouse College, after a brief battle between her GPS and the traffic gates that blocked our intended entry to the visitors’ parking lot. The disadvantage of hosting the Istanbul Center’s Southeastern Art and Essay Contest Awards Ceremony at Morehouse is the traffic, but that issue is hard to avoid anywhere within the busy Atlanta Metro area in the late afternoon. Morehouse traffic officials had been very helpful in directing us back toward the official entry to the college, where we were at once greeted by a gatesman who mapped out the rest of our route to the Leadership Center. We came to this event on March 25, 2011, to celebrate with the winning students, teachers, sponsors and Istanbul Center representatives. These ceremony participants represent over 2,500 entries from schools in the Southeast who participated in the art and essay contest this year.

Once inside the building we knew we were in the right place. The smell of Turkish spices in the air immediately awakened our senses. After signing in, we were invited to visit a make-shift exhibition hall adjacent to the center’s lobby, where the winning art and essay works were mounted on mattboards and set up on easels around the room. Since the welcoming reception had not officially started yet, we wandered into the “gallery” area and enjoyed looking at and reading the display. We equally enjoyed seeing the students and their families posing for photos near their work, with smiles stretching across their beaming faces.

Once inside the building we knew we were in the right place. The smell of Turkish spices in the air immediately awakened our senses. After signing in, we were invited to visit a make-shift exhibition hall adjacent to the center’s lobby, where the winning art and essay works were mounted on mattboards and set up on easels around the room. Since the welcoming reception had not officially started yet, we wandered into the “gallery” area and enjoyed looking at and reading the display. We equally enjoyed seeing the students and their families posing for photos near their work, with smiles stretching across their beaming faces.

Once the reception started, we all made a beeline toward the tables of food. There were fruits and sandwiches in the center tables; and along both sides of the lobby were several tables of Turkish pastries. Several IC volunteers were serving the food and drinks while chatting with the various attendees. Several people had come from outside of Atlanta (from various points in Georgia, Florida, Alabama, South Carolina and even some sponsors all the way from Turkey). So, the spread of food was a very welcoming way to begin this celebration. The lobby was full of chatter, as people freely introduced themselves in the warm environment that the Istanbul Center created for this day.

After about an hour of eating and “schmoozing,” Sedat Memnun (Director of Educational Programs and Tarik’s left hand for this event) started corralling the audience into the auditorium. Debi West was serving as the “Emcee” of the ceremony — a logical choice for such a position due to her effervescent personality, as well as her students’ experience in the competition. The adjudication has always been a blind process at all levels and judges are only aware of a number for each entry. Debi’s students typically win awards, including honorable mention, third, second and first place. The first year her student won a trip to Turkey, Debi got hooked into the “life-changing” outcomes of this program. Now when her students gain those coveted awards, she hands off the teacher’s trip to one of her colleagues at North Gwinnett High School.

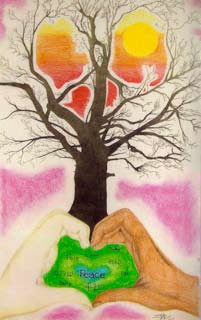

Following a speeches by Tarik Celik and some of the other program co-sponsors, the awards were presented to the students. As the winners’ names were called, the students and teachers came to the stage to receive their certificates and monetary awards. The Emcee asked some of the winners to quickly deliver a prepared description of their winning piece. Michelle Partogi, the second place winner for the Georgia high school art contest and third place winner for the Southeast high school art contest reinforced the importance of this year’s theme, “Empathy: Walking in Another’s Shoes,” particularly in consideration of her own nerves as she quickly critiqued her own winning graphic design in this public setting. Other students, such as Gowan Moise of Trickum Middle School in Georgia, seemed to be ready to start his stump speech for a future election. All in all, the spirit of the students’ work set a tone of hope and promise for a new day, toward what Fethullah Gulen describes as “an island of peace.”

Following a speeches by Tarik Celik and some of the other program co-sponsors, the awards were presented to the students. As the winners’ names were called, the students and teachers came to the stage to receive their certificates and monetary awards. The Emcee asked some of the winners to quickly deliver a prepared description of their winning piece. Michelle Partogi, the second place winner for the Georgia high school art contest and third place winner for the Southeast high school art contest reinforced the importance of this year’s theme, “Empathy: Walking in Another’s Shoes,” particularly in consideration of her own nerves as she quickly critiqued her own winning graphic design in this public setting. Other students, such as Gowan Moise of Trickum Middle School in Georgia, seemed to be ready to start his stump speech for a future election. All in all, the spirit of the students’ work set a tone of hope and promise for a new day, toward what Fethullah Gulen describes as “an island of peace.”

The first time I heard the expression,“creating an island of peace,” I was astounded by its poignant simplicity. It was shared at an Istanbul Center “Dialogue Dinner” led by Kemal Korucu (2005), who cited the “heaven-bent” messages of Gulen toward building authentic spaces where tolerance and understanding may grow.1 “If we build an island of peace, even if it is a small space, we can connect it to another small island of peace and thus create a region of peace. Our next step is to connect this region of peace to another region of peace, and in doing so we create a state of peace.[1] Following the original intention, we then connect one state of peace to other states of peace and thereby we have a peaceful nation. Finally, we connect the peaceful nations together and (eh voila!), we have a peaceful world.” Talk about peace is easy to do, but actually working toward it requires small steps that gradually bear fruit. Dalia Mogahed, member of the US Whitehouse Advisory Council on Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships, has recognized the Gulen movement as “a model and inspiration for all those working for the good of the society” largely because of his emphasis on education and altruism. [2]

The first time I heard the expression,“creating an island of peace,” I was astounded by its poignant simplicity. It was shared at an Istanbul Center “Dialogue Dinner” led by Kemal Korucu (2005), who cited the “heaven-bent” messages of Gulen toward building authentic spaces where tolerance and understanding may grow.1 “If we build an island of peace, even if it is a small space, we can connect it to another small island of peace and thus create a region of peace. Our next step is to connect this region of peace to another region of peace, and in doing so we create a state of peace.[1] Following the original intention, we then connect one state of peace to other states of peace and thereby we have a peaceful nation. Finally, we connect the peaceful nations together and (eh voila!), we have a peaceful world.” Talk about peace is easy to do, but actually working toward it requires small steps that gradually bear fruit. Dalia Mogahed, member of the US Whitehouse Advisory Council on Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships, has recognized the Gulen movement as “a model and inspiration for all those working for the good of the society” largely because of his emphasis on education and altruism. [2]

As we complete the fifth year of this contest, we now have a better idea of how the contest can positively impact our communities at precisely this level. For each of the individuals who have written about their experiences in this monograph, we see commitments to learning that lead well beyond the comfortable boundaries of ordinary experience, whether it is searching for ones’ roots, establishing new roots in a new land, or comparing different cultures at multiple levels and transforming that corrupting agent of fear into a willingness to give unselfishly. Each written experience echoes the importance of synergy — to create something together that is much better than what the individual can produce alone. College students, secondary students, teachers, administrators and parents meet new cultures in an authentic way and learn to accept people’s differences as a “spice of life” rather than an invading force. In the process of discovery, they discern that the differences between their culture of origin and the new cultures (they come in contact with during the course of the contest) have a valuable place in the definition of our collective humanness. The arts, both visual and literary, are the most perfect vehicles for this.

As we complete the fifth year of this contest, we now have a better idea of how the contest can positively impact our communities at precisely this level. For each of the individuals who have written about their experiences in this monograph, we see commitments to learning that lead well beyond the comfortable boundaries of ordinary experience, whether it is searching for ones’ roots, establishing new roots in a new land, or comparing different cultures at multiple levels and transforming that corrupting agent of fear into a willingness to give unselfishly. Each written experience echoes the importance of synergy — to create something together that is much better than what the individual can produce alone. College students, secondary students, teachers, administrators and parents meet new cultures in an authentic way and learn to accept people’s differences as a “spice of life” rather than an invading force. In the process of discovery, they discern that the differences between their culture of origin and the new cultures (they come in contact with during the course of the contest) have a valuable place in the definition of our collective humanness. The arts, both visual and literary, are the most perfect vehicles for this.

The broader implications for developing respect for “the other” through habits of thorough examination are reflected in many religious and philosophical systems around the world:

In Buddism we speak of the world of phenomena (dharmalakshana). You, me the trees, the birds, the squirrels, the creek, the air, the stars are all phenomena. There is a relationship between one phenomenon and another. If we observe things deeply, we will discover that one thing contains all things. If you look deeply into a tree, you will discover that a tree is not only a tree. It is also a person. It is a cloud. It is sunshine. It is the Earth. It is the animals and the minerals. The practice of looking deeply reveals to us that one thing is made up of all other things. One thing contains the whole cosmos.[3]

In many of the writings of Thich Nhat Hanh, this Buddhist Master refers to habits of “looking deeply,” involving a natural recourse to compassion and empathy, as a kind of horizontal consciousness. Master of American Buddhism, Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, labels the development of these habits as the practice of “universal loving friendliness.”[4] The Christian theological term, “agape” (selfless love), also conforms to Gunaratana’s sense of loving friendliness — a love that is distinct from romantic or erotic emotional feelings. Agape also refers to the sharing of a ritual meal, such as the “love feast” practiced within early Christian settings. The ancient agape meal was probably similar to the Jewish Passover meal and became the foundation for the Eucharist in Christian churches. A pre-cursor to the American “pot-luck dinner,” all members were expected to bring something to the charity supper and share in the readings or testimonies associated with the event. The tradition was dismissed by the Catholic Church in 393 C.E., but the Founding Father of Methodism, John Wesley, tried to revive the practice of the “love feast” in the 18th century. The practice unfortunately died out in the 19th century.

In many of the writings of Thich Nhat Hanh, this Buddhist Master refers to habits of “looking deeply,” involving a natural recourse to compassion and empathy, as a kind of horizontal consciousness. Master of American Buddhism, Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, labels the development of these habits as the practice of “universal loving friendliness.”[4] The Christian theological term, “agape” (selfless love), also conforms to Gunaratana’s sense of loving friendliness — a love that is distinct from romantic or erotic emotional feelings. Agape also refers to the sharing of a ritual meal, such as the “love feast” practiced within early Christian settings. The ancient agape meal was probably similar to the Jewish Passover meal and became the foundation for the Eucharist in Christian churches. A pre-cursor to the American “pot-luck dinner,” all members were expected to bring something to the charity supper and share in the readings or testimonies associated with the event. The tradition was dismissed by the Catholic Church in 393 C.E., but the Founding Father of Methodism, John Wesley, tried to revive the practice of the “love feast” in the 18th century. The practice unfortunately died out in the 19th century.

It is a very sad for me to see the intentional limitations that some “religious people” cling to in our contemporary world. The angry response that Muslims have received in Murfreesburo, Tennessee (or even New York City, or Lilburn, Georgia) as they try to build an Islamic Center to serve the area’s Muslim community is voiced by the cry of an angry Protestant on national television, “I didn’t say we hate them … we just don’t want them here!”55 It is clear that this person has not met the true nature of Islam. The Islam I know is a religion of tolerance, compassion, and peace. It is also the Islam that students and teachers meet as they explore the themes of this contest. The lovely people who host them during their winning trip to Turkey provide a clear example of the kindness and gentleness that is generally associated with the Muslim practitioner.

It is a very sad for me to see the intentional limitations that some “religious people” cling to in our contemporary world. The angry response that Muslims have received in Murfreesburo, Tennessee (or even New York City, or Lilburn, Georgia) as they try to build an Islamic Center to serve the area’s Muslim community is voiced by the cry of an angry Protestant on national television, “I didn’t say we hate them … we just don’t want them here!”55 It is clear that this person has not met the true nature of Islam. The Islam I know is a religion of tolerance, compassion, and peace. It is also the Islam that students and teachers meet as they explore the themes of this contest. The lovely people who host them during their winning trip to Turkey provide a clear example of the kindness and gentleness that is generally associated with the Muslim practitioner.

I hope that the goal of teaching universal “loving friendliness” or “agape” will continue to find ways into our educational venues and can eventually overcome the well-worn corrupted views of “the other,” especially concerning differing religions and philosophies. Our children will need this expansive attitude, this horizontal wisdom, to survive the 21st century. And it will require the synergy of multiple organizations’ professionals working together to nurture the development of our humanness in the educational process.

1. For more information on the Gulen Movement, see: http://allaboutgulenmovement.blogspot.com/

2. http://en.fgulen.com/press-room/news/3355-gulen-movement-an-inspiration-for-all-says-obamas-muslim-advisor-mogahed.html

3. Hahn, T.N. (1999) Going home: Jesus and Buddha as brothers. New York: The Berkley Publishing Group. pp.4-5.

4. Gunaratana, B.H. (2002). Afterward, in Mindfullness in plain English. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications. Pp. 321-324. Gunaratana comments on the role that metta or “loving kindness”, or as Gunaratana prefers “loving friendliness”, plays in the building of positive relationships.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.