As both a candidate and as president, Ebrahim Raisi has repeated a basic mantra: that he will seek to quickly improve relations with Iran’s neighbors, and particularly the Arab Gulf states. In terms of his motivations for this push, two points are undeniably important. First, there is no indication that Raisi’s stance represents a sea change in terms of the mindset of the ruling elite in Tehran, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, regarding Iran’s regional posture. Put simply, Raisi’s foreign policy agenda will, even at its utmost, not represent a strategic shift. What is happening is more about the need to make tactical foreign policy adjustments to accommodate the domestic and economic challenges facing the regime.

This takes us to the second factor, which is to suggest that much of Raisi’s call for détente with neighboring states is rooted in the challenges he faces. The most obvious is in the realm of the economy. Only seven months into office, Raisi’s government is already close to bankruptcy. This has created its own socio-economic pressures in a country that is restless and arguably on a tinderbox.

The fact that Raisi’s first two provincial trips were to the impoverished regions of Khuzestan and Baluchistan underscores what the president’s advisers see as his most acute vulnerabilities. Besides taking pre-emptive steps in the hope of avoiding popular unrest, Raisi also has his own self-centered political motives. The general public attitude is that Ayatollah Khamenei selected Raisi to be president, and that he might even be on the shortlist as Khamenei’s successor. Raisi, to legitimize his presidency and to elevate his stature with the supreme leadership in mind, has to therefore quickly create pockets of goodwill for himself in Iranian society.

This, for example, explains why his economic policies so far have been extremely similar to those offered by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005: populist and aimed at the lower-middle and working classes. Not only does Raisi have to work harder to generate a base for himself than Ahmadinejad did — the latter actually had a base of popular support in society — but he has far fewer financial resources at his disposal to do so. Unlike in 2005, today’s Iran has been hard hit by sanctions and the economy is on life support.

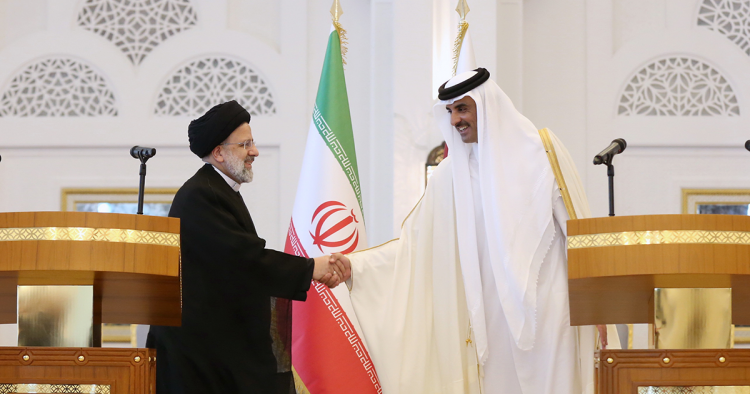

This domestic economic reality is directly linked to Raisi’s call for détente with the Arab states. Raisi needs to lower the cost of Iran’s foreign policy agenda, and he seemingly has the support of Khamenei. At the very least, the regime in Tehran would be putting itself at great risk if it further invested in regional projects at the expense of tackling domestic demands. This is the central impetus behind Raisi’s regional outreach, as stressed by his state visit to Qatar in February 2022. The rest of the regime is doing its part to promote this message and facilitate its acceptance by neighboring Arab states.

The Saudis are the principal audience. The message from Tehran to the Gulf Arabs is plain and overly simplistic: The Americans are untrustworthy, uninterested in the future of the Middle East, and it is time for regional actors to begin the arduous process of compromise-making with the hope of moving the region toward a new security arrangement. That said, neither Raisi, nor his Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian has yet to articulate an original regional security architecture.

The Raisi government has made references to the Hormuz Peace Endeavor (HOPE), but there are two problems with HOPE. First, this initiative was launched by his predecessor, President Hassan Rouhani. Second, the Arab states have so far been very indifferent toward HOPE, so its utility is limited. Only time will tell if the Raisi government can formulate some kind of regional initiative that might be of interest to the Arab Gulf states. There is little sign of it at present though. In the meantime, Tehran is instead likely to push ahead with the process of détente on a bilateral basis with neighboring Arab countries.

Again, Riyadh will remain Tehran’s top focus. Bahrain is too small and essentially inconsequential for it to be a priority for Iran while the UAE is viewed by the Iranians as open to some kind of accommodation, as evidenced by the number of rare high-profile official visits there. With Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman, Iran will maintain a policy of continuity. Where this process of compromise will take place geographically is hard to judge. Syria and Yemen are often mentioned as suitable areas for an Iranian-Gulf understanding, but neither theater offers a straightforward political environment for compromise-making.

Although the diplomatic rewards would be considerable, the likelihood of a compromise over the thorny regional conflict is still somewhat remote. The best that can be hoped for at the moment is for Iran and the Gulf states to identify areas of mutual interest for cooperation. In Syria, for example, Tehran sees benefits in allowing Gulf capital to underwrite reconstruction projects in which Iranian companies hope to secure some of the contracts. What is still unknown, however, is the extent of Tehran’s sway over its key Arab partners — such as the Assad regime or the Houthis — that need to be included in any Iran-Gulf process of détente.

An alternative and much more straightforward proposition is for Iran and the Gulf states to seek détente in areas that are centered on bilateral relations. One such area is maritime security cooperation. The number of incidents involving vessels in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea in recent years — including the seizure of vessels and armed drone attacks on ships — makes this a highly relevant area for possible cooperation between Iran and its Arab neighbors. But for this to happen, Tehran would first need to admit there is a problem.

In early August 2021, Iranian officials at the U.N. in New York complained about “false flag” operations in regional waters carried out by Israel and its allies with the aim of framing Iran. At the same time, Tehran has declared its openness to working with neighboring states regarding maritime security and freedom of navigation. These two positions offer a contrast that poses a policy dilemma.

In essence, the Iranian position of regional cooperation appears at the moment to be pre-conditioned on neighbors not having security and military ties with Israel. This in turn puts the Gulf states, particularly the UAE and Bahrain that have diplomatic relations with Israel, in a tough spot. The challenge for the Gulf states is to press Tehran to decouple possible areas of tactical cooperation, such as maritime security, from the broader strategic foreign policy choices each country makes.

Raisi’s possible plans to institutionalize the “Axis of Resistance”

What is equally worrisome is that the question of Israel remains an inherent ideological component of Tehran’s proclaimed “Axis of Resistance.” Statements by the Raisi government, including from Foreign Minister Amir-Abdollahian, suggest that Tehran intends to “institutionalize” this political-military model. This is at least the rhetoric from the new Iranian government, which creates its own challenges: how to reassure the concerned Gulf states about Iran’s regional ambitions when it openly declares it wants to strengthen the one aspect of Iranian policy they resent the most.

Nevertheless, there is no evidence so far that the idea of “institutionalizing” the “Axis of Resistance” is anything other than posturing by a Raisi government eager to show itself to be different from its predecessor. That said, while Raisi has not yet articulated a specific plan, there are signals about how this “institutionalization” of the “Axis of Resistance” might start to shape up in the near future. For example, in August 2021 the leaders of the pro-Iran Iraqi militias known as the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces or PMF) began to speak about the need to create “an Iraqi Revolutionary Guards.” This is at least what Falih al-Fayyadh, head of Iraq’s PMF, told Hossein Salami, the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards.

Put simply, given Iran’s limited financial resources and its simultaneous pursuit of détente with the Gulf states, the most Tehran can do at the moment on the issue of “institutionalizing” pro-Iran proxy militants is to help such armed actors become permanent political fixtures in the countries where they operate. The main issue for the Gulf states is the following: If they choose to accept Iran’s overtures and the call for regional cooperation, how can they then nudge Tehran away from investing further in the “Axis of Resistance,” which is essentially an anti-status quo model and therefore an incitement for further regional instability?

The Raisi government has proclaimed Iran’s “neighbors” and “Asia” more broadly to be the primary interest of Iranian foreign policy. In this sense, “Asia” here is a continuation of the “Look East” policy, in which Ayatollah Khamenei continues to have great hopes. It centers on the idea of closer relations with China and Russia in particular. That said, this is not the first time a push has been made in this direction.

President Ahmadinejad also had great plans for his “Look East” and “Look East and South” agenda, targeting Asia and Africa and Latin America respectively. In that sense, Raisi’s idea is not an original one. The question is whether he is likely to do better than Ahmadinejad did when it comes to execution. Two factors are important to underscore when assessing this question.

First, it has to be noted that there is a significant degree of policy continuity. Khamenei will continue to micro-manage relations with both Russia and China. The foreign ministry under Raisi will not be given a new mandate but only allowed to facilitate efforts already initiated by Khamenei’s special envoys to those two countries.

There is, however, a second factor that might work to Tehran’s advantage. In 2005 when Ahmadinejad first launched the “Look East” policy, Russia and China both had considerably better relations with Washington. Beijing and Moscow voted with the U.S. at the U.N. against Iran’s nuclear program and for sanctions.

Today, Russia and China are each locked in a fierce contest for global influence with the U.S. Neither has an incentive to see the U.S. policy of “maximum pressure” against Iran succeed. If it does, then it can be replicated elsewhere in the world to the detriment of Russian and Chinese interests. For now, “Look East” will mean policy continuity, but it is unlikely to be the silver bullet Khamenei wants to solve all of Iran’s problems.

Finally, while Khamenei’s “Look East” policy might make some political sense — since it is aimed at cementing ties with two other states that have troubled relations with the U.S. — it is clearly wanting as a means to deal with Tehran’s most immediate trials, which are economic in nature. In Tehran, critics of the “Look East” policy point to the obvious: that neither China or Russia has done more than make promises to Iran. For example, thus far neither country has actually invested in a strategic sense in Iran’s oil and gas industries. Indeed, for now the “Look East” policy continues to be a theoretical aspiration, not a working policy. This is despite the fact that Chinese purchases of Iranian crude oil, against U.S. sanctions, have been a lifesaver for Iran in recent years.

In short, Raisi’s call for détente with the Arab Gulf states is not yet rooted in a deep moment of policy reexamination in Tehran. It is a case of Iran accepting that open-ended or heightened regional tensions pose a risk to its internal stability. The Gulf states can still grasp this moment to nudge Iran toward re-examining its regional policies, however. In fact, if they can identify the most suitable “carrots and sticks” vis-à-vis Iran, it will signal to Tehran that they are interested in dialogue provided Tehran is sincere about changing the policies that so many of its neighbors resent.

Alex Vatanka is the Director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C. His most recent book is “The Battle of the Ayatollahs in Iran: The United States, Foreign Policy and Political Rivalry since 1979.” You can follow him on Twitter @AlexVatanka. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Iranian Presidency/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.