Iraq’s economic and fiscal crises, which came to the forefront this year following the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, were bound to happen at some point. What corona and the ensuing drop in oil prices and declining demand for oil did is accelerate the timing, according to the recently released Iraqi government white paper, a report of the Emergency Cell for Financial Reform. What the paper doesn’t predict is that in the next 6-12 months, and possibly beyond, we could see a worsening of the crisis with both current and future governments trying to adjust oil production and revenues in an effort to contain public discontent.

The Emergency Cell for Financial Reform was set up in May 2020 to, according to the government, manage Iraq’s financial situation in light of the current crisis and develop the necessary solutions to achieve financial reform and improve the performance of financial institutions. Managing the crisis is proving to be an exercise in futility and an additional strain on the state’s financial capacity. Reforming the state financial structures is a long-term exercise that will require more than just the current government’s goodwill.

The white paper pretends to offer a set of reforms and policies that it admits would require harsh and bitter measures to address Iraq’s financial predicament. The paper includes a number of proposed reforms, from introducing changes at the Ministry of Finance to have more control over financial and fiscal policies, to reforming the contracted economic sectors and dysfunctional state administration, to rebuilding the dilapidated infrastructure and providing basic services. But of all the proposed policies, two are determinant factors in overhauling the system: how to deal with the inflated and unproductive public sector that is draining Iraq’s budget year after year and turning Iraq into a poor third world country despite its rich resources, and how to put an end to Iraq’s dependency on oil revenues and start creating a productive economy that relies first and foremost on the private sector.

The ballooning public sector

To halt and ultimately reverse the financial bleeding, the governments of Iraq, current and future, will need to address the disastrous state of the public sector and its associated wages. Between 2004 and 2020, public servants’ wages and pensions increased by 400 percent in real terms, accounting for the largest component of public expenditures, according to the paper. In the same period, the number of civil servants increased by more than three-fold while labor productivity rose by only 2 percent for the whole period — to stand at about a quarter of what it was in 1979. This is where radical changes are needed in the governance of public finances to transition to a management of state revenue that focuses on delivering public services rather than sustaining and expanding public sector employment. The authors of the paper offer to put in place and operate public financial and investment management systems. However, in the absence of a concrete implementation plan, those proposed systems remain vague.

If nothing is done to address the current state of the public sector, the biggest dilemma is that the population of Iraq, which witnessed a growth rate of 53 percent from 2004 to 2020 to reach a current estimated total of 40.2 million, is projected to grow by a further 25 percent by 2030 to reach 50.2 million. That means a cumulative 5 million people will enter the labor market between now and 2030, according to projections from the white paper.

There is simply no way that the public sector can absorb those numbers. An urgent but painful measure would be to start dismantling the heavily-subsidised state-owned enterprises and shift the burden to a private sector that is yet to be empowered to carry out the task. Whether the promised action plan that is set to follow the approval of the white paper by Parliament will tackle this double measure and exactly how it would do that remain to be seen.

The state budget shortage and the government’s struggle to pay public wages and pensions this year following the collapse of oil revenues due to the coronavirus pandemic made the public sector’s size and salaries hard to ignore.

If anything, the coronavirus pandemic and the collapse of oil revenues has only drawn attention to a long-known fact: Iraq is doomed if it continues to totally rely on its oil resources to survive economically, socially, and politically. Oil revenues account for 91 percent of state revenue. The last financial crisis of 2015-16 saw payroll payments in Iraq account for 88 percent of oil revenues. Today, they are expected to account for 122 percent of the projected oil revenue in 2020.

A troubled outlook

Things are unlikely to change in the near future, as the fundamentals in the oil markets remain shaky for 2021. Talk of an oil demand peak and potential oversupply well into 2021 is gaining momentum, putting question marks over an oil price recovery in the next 6-12 months. That leaves Iraq with a bigger gap between its necessary expenditures and the expected oil revenues, pushing the budget deficit to record levels.

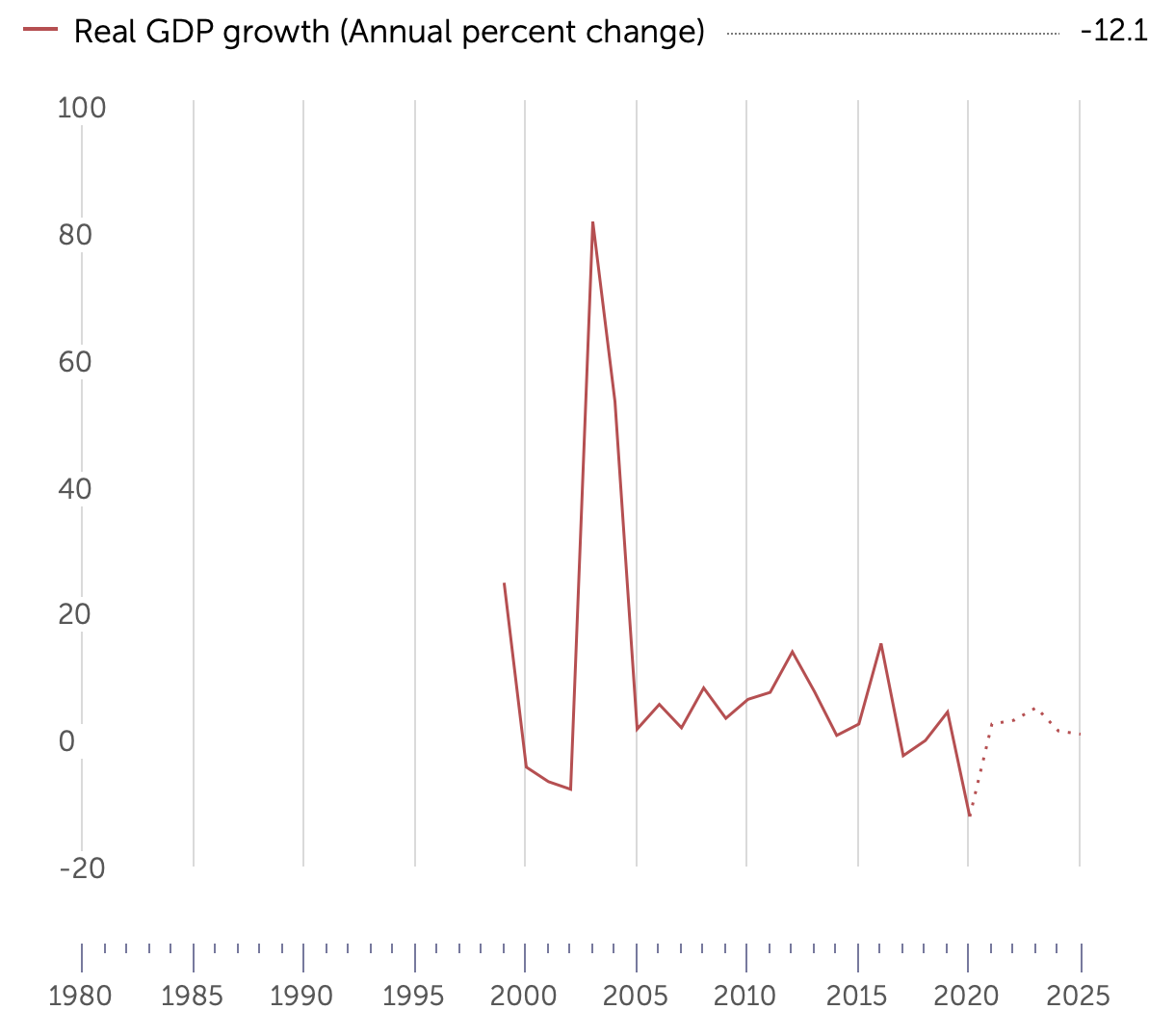

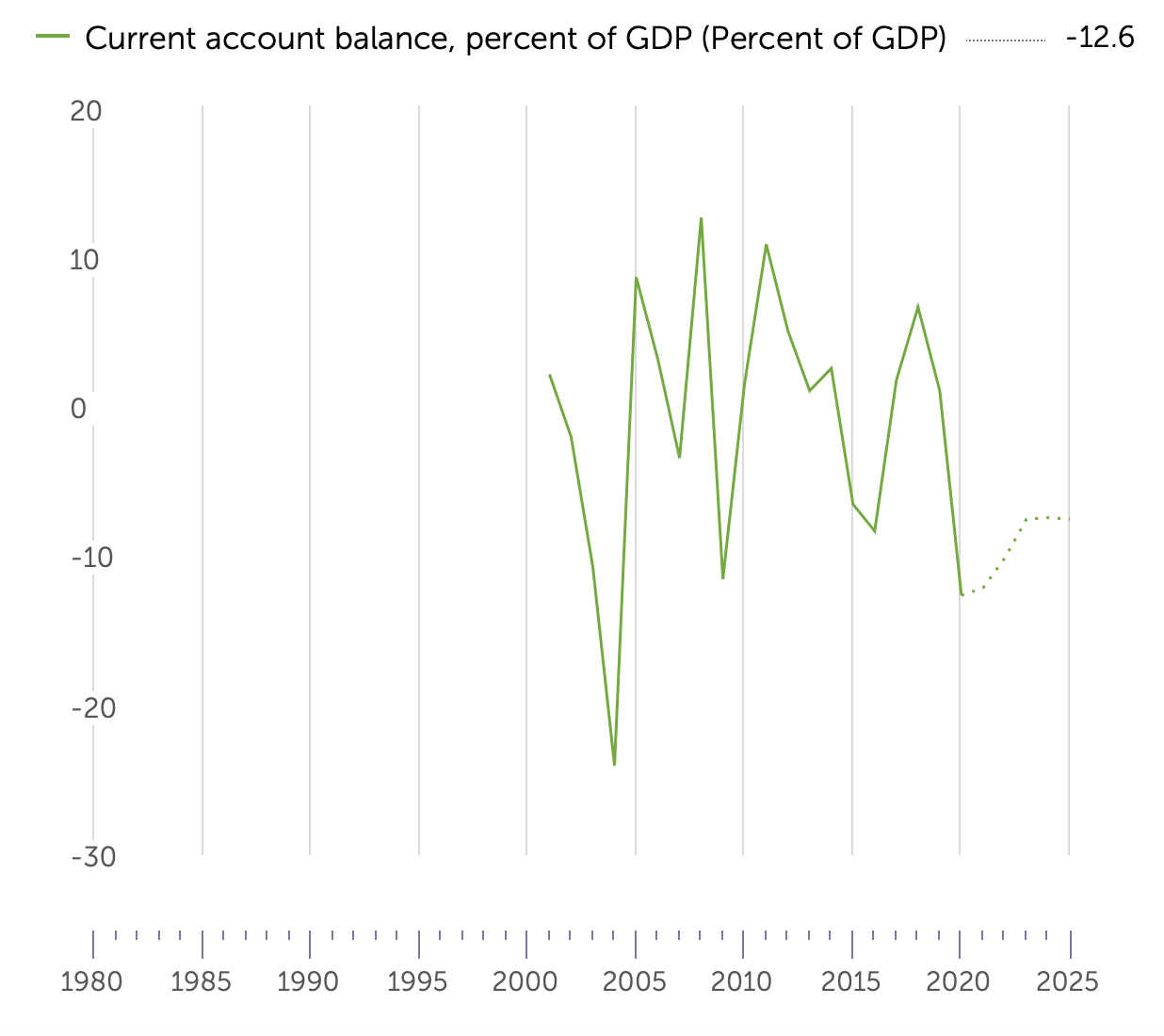

The IMF economic and fiscal indicators published in October give a somber reading of where the country currently stands. Projected real GDP is expected to drop by 12.1 percent in 2020. At current prices, GDP stands at $178 billion with a projection that it could get close to the 2019 GDP level of $230 billion by 2025. More striking is the negative current account balance of -$22.5 billion compared with a positive $15.3 billion in 2018. The IMF projection puts the 2025 expected current balance at -$18 billion. As a percentage of GDP, the current account currently stands at -12.6 percent and a projected -7.5 percent in 2025.

In the previous crisis in 2015-16, Baghdad managed to finance the budget deficit through external and domestic borrowing and continued on the same track until it found itself today with accumulated debts that are a conundrum to manage. The Ministry of Finance has a bill in front of Parliament to allow it to borrow an additional $35 billion to pay wages till the end of the year. Parliament is reluctant to endorse the legislation. Finance Minister Ali Allawi admitted that the only other feasible option, monetary financing by the Central Bank of Iraq, would have long-term adverse consequences. That leaves his ministry, the government, and Parliament with one course of action: making major spending cuts, or what the paper rightly called a “radical and immediate program to stop the bleeding of the budget.” This translates as cutting the numbers and reducing the salaries and benefits of public sector workers.

The authors of the white paper say it was written “with a deep awareness and recognition of the urgent need that implementation of the core economic reforms can no longer be postponed or carried forward.” We can no longer hope that oil prices will somehow rise again and give us the fiscal space to continue with business as usual, they conclude.

What the white paper calls “urgent remedies” to apply in the immediate and medium term (three to five years) in order to “shift the ailing economy from the intensive care unit to the intermediate care ward” focus on structural reforms in state institutions that, in an ideal world, would usher in a new and vibrant economy with a viable and sustainable state structure. What it lacks is the vehicle to transition from the current state of dilapidation to a new state of a recovering economy and state. Furthermore, those remedies in no way address the current fiscal and budgetary crises that are set to continue into 2021, an election year that is expected to return to office the same political class responsible for the economic policies — or the lack thereof — that led Iraq to its current predicament.

Failing the political courage and the buy-in and acceptance of the Iraqi people and above all the political elites that the authors of the white paper put as a condition for implementing the recommended reforms, there remains one path that could lend a helping hand: outside pressure. Following the crash in oil prices in 2015, Haider Abadi’s government turned to international institutions for help. The special drawing rights that the IMF provided were made conditional on implementing economic reforms, improving governance, and reining in budgetary spending. However, once oil markets recovered and revenues were abundant again, Iraq went back to its old habits. The global economy and the oil markets are unlikely to recover to pre-pandemic levels in 2021, creating an opportunity for international institutions to revisit their leverage with Iraq on more sustainable terms.

Ruba Husari is an expert and analyst on Middle East energy issues based in Dubai. She is the managing director of OZME Consultants and a non-resident scholar at MEI. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by Murtadha Al-Sudani/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.