This essay is part of the series “All About China”—a journey into the history and diverse culture of China through essays that shed light on the lasting imprint of China’s past encounters with the Islamic world as well as an exploration of the increasingly vibrant and complex dynamics of contemporary Sino-Middle Eastern relations. Read more ...

Given the prominence of calligraphy in the traditional arts of both the Islamic world and China, it is only natural that Islamic calligraphy plays an important cultural role in Chinese Muslim communities. The art form’s survival over the centuries in China, even during prolonged periods of isolation from the rest of the Islamic world, reflects the strength of Chinese Muslims’ religious traditions, as well as the critical function of the written word within these traditions.

The history of Islam in China remains among the most understudied topics within the fields of both Islamic and Chinese studies.[1] The development of Islamic art and architecture in China has been particularly neglected, and like the recent article on mosque architecture in China published as part of this same series,[2] this essay seeks to begin to address this deficiency. The following examples of Chinese Islamic calligraphy tell the stories of diverse Muslim communities in China, the challenges they have faced through the centuries, and the different ways they have adapted this traditional Islamic art form.

It is important to note the obstacles that Chinese Muslims have faced in protecting and passing on their cultural inheritance. They have not only survived periods of enforced separation from the rest of the Muslim world but have also endured numerous periods of state-sponsored violence. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese Muslims have been killed during government campaigns to suppress resistance movements by Muslim communities in different regions of China. In the modern period, Muslim communities (together with all other religious communities, and much of the general population) suffered during the political campaign known as the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Mosques throughout China were either damaged or destroyed, along with unknown quantities of religious materials and texts, especially works of calligraphy on paper or wood.

Early History

During the first few centuries of the Islamic era, calligraphic styles emerged and were standardized in different regions of the expanding empire. Several of these styles were transmitted to China by the Muslim traders who had been traveling to China since the earliest days of Islam. The most common surviving examples of these styles can be seen engraved in the tombstones of Muslim traders from the Arab Middle East, Persia, and Central Asia who died and were buried in China.

One of the earliest and most important communities of Muslim traders was established in Quanzhou, along China’s southeastern coast, in present-day Fujian. Muslim traders first settled in this port city in (roughly) the tenth century, and a Muslim presence has continued there to this day. The city of Quanzhou became so well known in the Islamic world that it was commonly referred to as Zaytun (olive) in Arabic sources.

The calligraphy of the earliest of the tombstones reflects the styles that were common in the Middle Eastern and Central Asian homelands of the traders. However, over the centuries, as links with the rest of the Muslim world died out, the style of the calligraphy began to change.

The following four photographs show the surviving entryway to one of the earliest mosques in Quanzhou, the Ashab Mosque. It has been renovated to show the original structure but has not been rebuilt. Damaged tombstones from local Muslim cemeteries are now stored within for safekeeping. A close look at the calligraphy shows how it developed over time. Of the tombstones that survive, most marked the graves of Muslims from Persia and Central Asia who died in Quanzhou during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. [Photos by Orlando V. Thompson II]

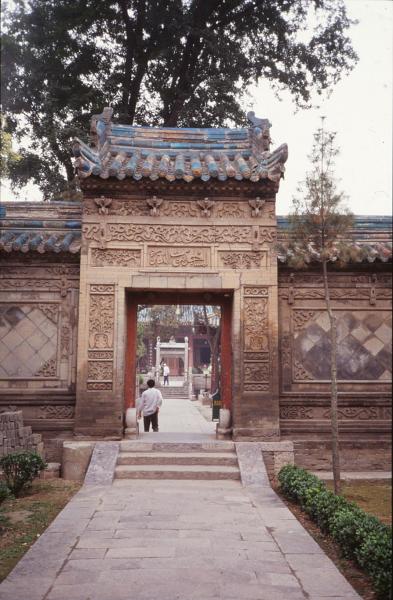

The Great Mosque of Xi’an

This extraordinary mosque reflects in many ways the seamless integration of traditional Chinese and Islamic aesthetic traditions. Islamic calligraphy is incorporated throughout the mosque in various media, including stone carvings, wooden inscriptions, and paper and silk scroll writing.

The largest migration of Muslims to China took place during the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1260-1368), when the Mongols, having conquered all of China, realized that they needed professionally trained men to carry out the governance of the empire. Officials, primarily Muslim, were recruited from the regions of Central Asia, Persia, and the Middle East that the Mongols had conquered. The recruits were assigned to every region of China, where many ended up settling permanently.

Over the centuries, these Muslim men adopted many, if not most, of their new communities’ cultural traditions while retaining their Muslim identity. At times, this mixing occurred voluntarily and naturally, as the foreign Muslim residents married local Chinese women over generations. At other times, the adoption of Chinese names, clothing, language, and customs was imperially commanded by the emperor. These Muslim communities later become known as the Hui and developed their own style of Chinese Islamic calligraphy.

From the Yuan period to the beginning of the twentieth century, Hui communities in the different regions of China followed different trajectories. Some communities flourished, while others faded away, and others became embroiled in communal conflicts or armed resistance to the state. There were both mass migrations and state-sponsored massacres of hundreds of thousands of Muslims in northwest and southwest China. Due to their different histories, regions have developed different customs and traditions, and the patchwork of varied influences is apparent to this day.[3]

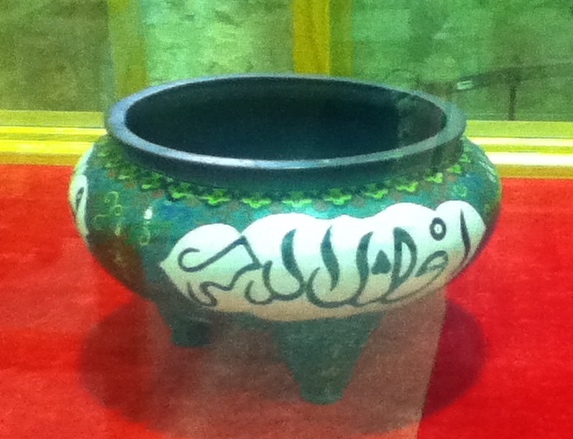

However, the word Sini (Arabic for Chinese) began to refer to the wide range of Chinese Islamic art forms: calligraphic scrolls on paper and silk, wooden carvings, various ceramic and porcelain products, and bronze incense burners (similar to those used by Buddhists and Daoists). Beginning in the Ming (1368-1644) period and continuing into the Qing (1644-1912) period, Chinese Muslims began acquiring these works of art that reflected both their Chinese aesthetic and their religious sensibilities.

Although over the years millions of these works were undoubtedly collected and displayed in homes, unfortunately very few remain. During the Qing dynasty, periods of state-sponsored violence, forced migrations within China, and escape into exile in surrounding countries (including present-day Kazakhstan, Burma, and Thailand) devastated communities. However, most of the destruction of artwork occurred during the modern period, specifically during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a time of extreme political chaos when violent campaigns attacking traditional culture and religion were carried out by Red Guards and civilian mobs. Any examples of traditional or religious art were zealously sought out and destroyed. Calligraphy on paper or silk scrolls was easily burned, as were inscriptions in wood, while porcelain and ceramic works with Islamic inscriptions were smashed. In some cases, the Muslim families would take the initiative in destroying works of art in order to protect themselves from persecution or harassment.

Personal and household items of Islamic art were not the only works that were destroyed. During this period, all houses of worship—including mosques, churches, and temples—were confiscated by state or local authorities and commandeered for other uses. Many mosques were destroyed, and almost all suffered extensive damage. It is said that during this period the only mosque that remained open in all of China was the main one in Beijing, which was kept open for use by the foreign Muslim diplomats living in the capital.

The small, durable bronze incense burners with Islamic inscriptions—perhaps the most common examples of Chinese Islamic art—would have been the most likely to survive this period of destruction. However, most of these had already fallen victim to a slightly earlier political movement, the Great Leap Forward (1957-1960). One of the major projects of this campaign was the rapid development of a small-scale steel industry that required rural households throughout the country to collect all goods made of metal (such as pans, pots, cooking utensils, and farming implements) and melt them down to produce steel. Needless to say, this particular campaign was especially disastrous for the rural population of China.

Recent Influences from the Middle East

Beginning in the early 1990s, Chinese Muslims were once again allowed to travel overseas to further their Islamic studies. When they returned to China, these travelers represented an important way for Chinese Muslim communities to reconnect with the Islamic heartlands and strengthen their religious understanding. However, there were also many unintended consequences. For example, students who had studied at the very conservative Islamic University of Medina in Saudi Arabia began campaigns to purify the practice of Islam in China. Mosques that reflected Chinese art and architectural styles were condemned as blasphemous for incorporating images and temple architectural forms. Over the past 20 years, thousands of mosques have been torn down and replaced with ones deemed more “authentic.” Many of these new mosques have also insisted on removing traditional Chinese Islamic inscriptions and replacing them with standard Arabic calligraphic styles.

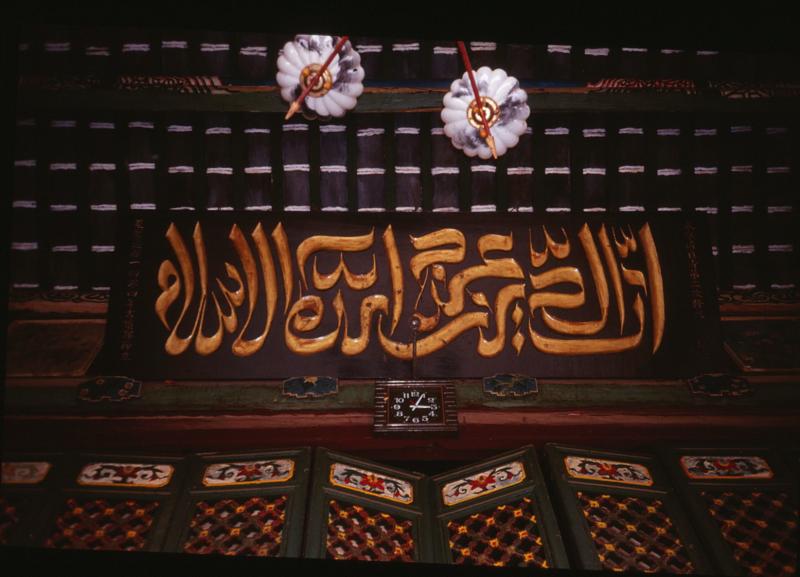

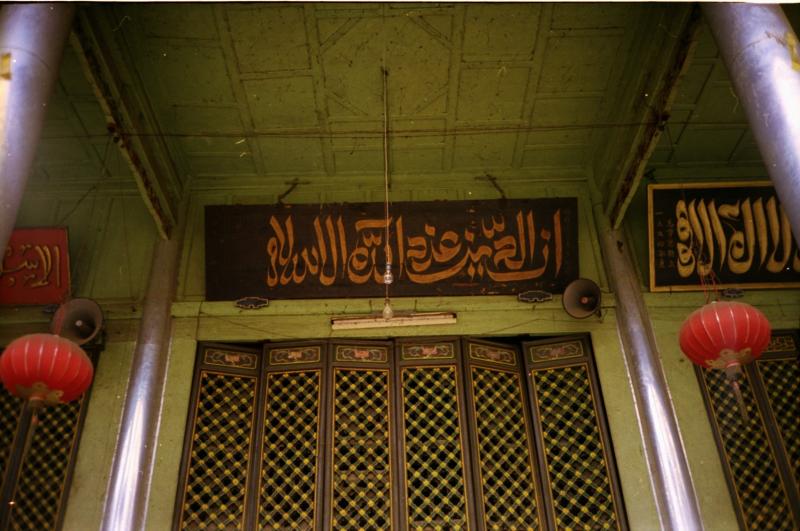

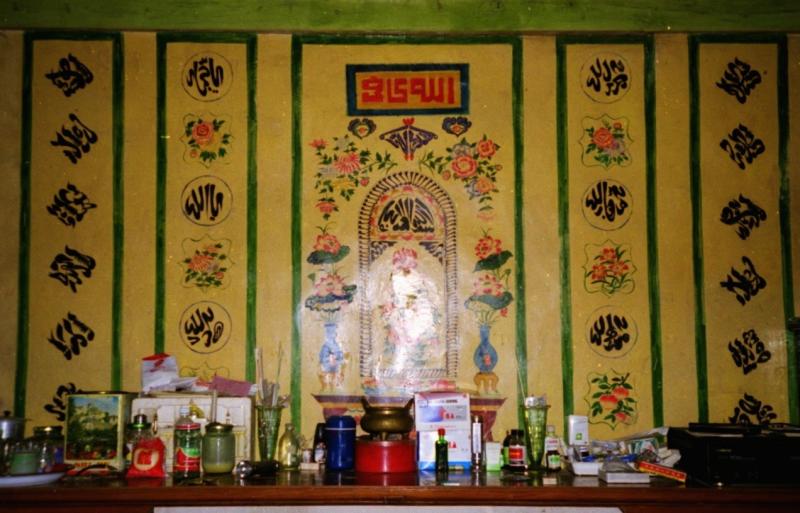

Below are several examples of the Islamic calligraphy traditionally found on wooden plaques above the entrances to mosques in Yunnan province in southwest China, as well as examples of the calligraphy from the mihrab[4] walls. Many, if not most, of these mosques no longer exist.

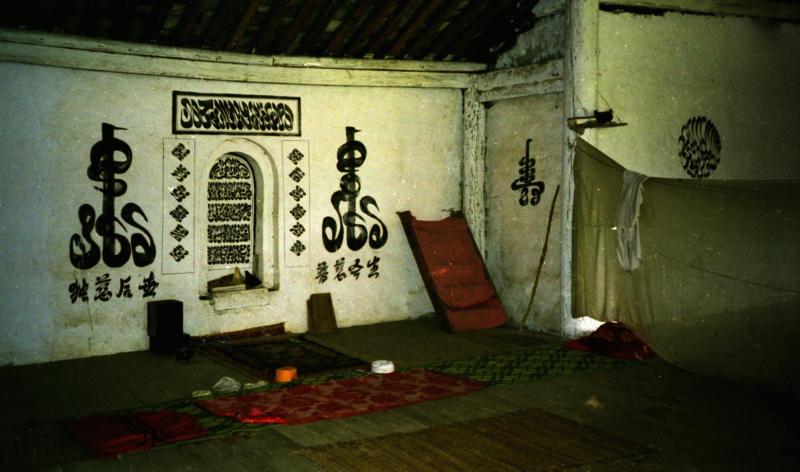

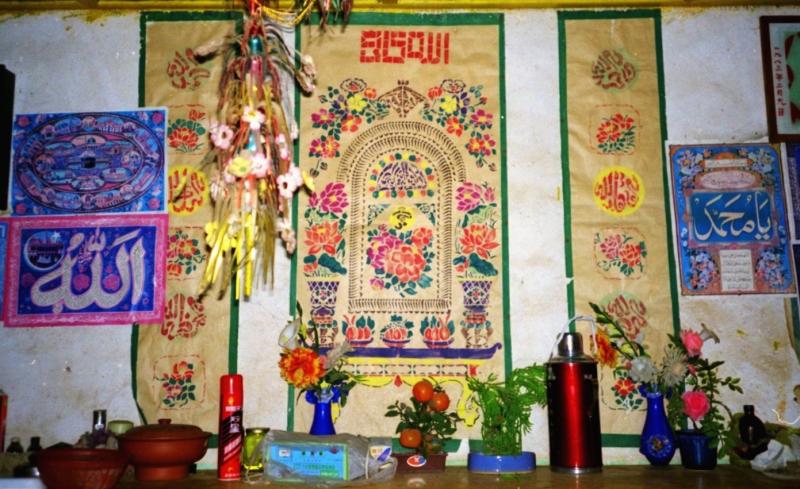

Traditionally, most Hui families, especially those living in rural areas, would have one wall of their main living room set aside for Islamic calligraphy and decorations. Below are a few examples of this practice. In the past, most of these decorations would have been made locally by craftspeople. However, over the past 20 years, as more ties have been made with Muslim countries, more and more families are choosing to decorate their homes with imported, mass-produced works. As demand for locally produced Islamic artwork declines and traditional Arabic styles gain popularity, there are fewer and fewer artisans knowledgeable about these forms.

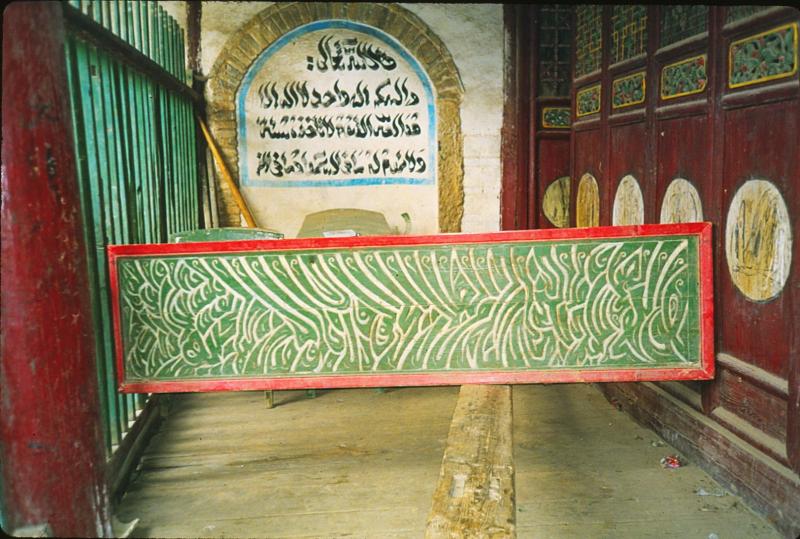

Some Chinese Muslim communities have also used Islamic calligraphy on funeral biers. Although this practice has only been documented in Yunnan thus far, additional research may reveal that it was once common throughout China. In Muslim societies, the deceased is traditionally wrapped in a white cloth and transported to the cemetery on a simple bier. However, while carrying out fieldwork among Muslim villages in Yunnan province, I happened to notice two examples of elaborately inscribed coffin-like biers. It is not known how many such biers survive today.[5]

Preserving and Exhibiting Chinese Islamic Calligraphy

Ma Guangjiang (Arabic name: Hajji Noor al-Din) is considered to be the most accomplished calligrapher specializing in traditional Chinese Islamic calligraphy. Trained in both China and the Middle East, his works have been displayed around the world. In an effort to promote and preserve China’s traditional Islamic calligraphy, he established the Chinese House for the Arts of Islamic Arabic Calligraphy in Zhengzhou, Henan Province in 2009. In addition to collecting surviving examples of Chinese Islamic calligraphy, the institute also offers classes in Sini calligraphy and works with museums and universities around the world to promote understanding of the history of the traditional Islamic arts in China.

At present there are only a handful of very small collections of Chinese Islamic artwork outside of China. The largest catalogued collection is at the Museum of Islamic Art in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. One of the smallest but most exquisite is at the David Collection of Islamic Art in Copenhagen. Although the collection only has five pieces, they are strikingly beautiful. In Qatar, Shaykh Faisal has a small collection of approximately a dozen pieces. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has several pieces, but they have not as yet been organized into a collection.

Images from the David Collection of Islamic Art

Three images from the Shaykh Faisal Museum

As international interest in China’s Islamic communities grows and as China continues to build strong relations with the countries of the Middle East, these developments will hopefully draw attention to the cultural dimension of Chinese Islam. As evidenced by this brief examination of the history of Chinese Islamic calligraphy, China’s Muslim communities have made important contributions to Islamic art despite their isolation from the Middle East and periodic episodes of government persecution. Though much of the artwork has been lost, there doubtless remains more of this rich heritage to discover, study, and protect.

Note: All photographs were taken by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Sources

“Islamic Calligraphy in China,” China Heritage Quarterly 5 (March 2006), http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=005_calligraphy.inc&issue=005.

Jacqueline Armijo, “Islam in China,” in Asian Islam in the 21st Century, eds. John Voll and John Esposito (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

David Atwill, The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856-1873 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005).

“Islam in China,” The David Collection, Copenhagen, https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/cultural-history-themes/islam-in-china.

Lucien de Guise, “From the Middle East to Middle Kingdom,” Saudi Aramco World 60, 4 (2009), https://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200904/from.middle.east.to.middl….

Ma Guangjiang, “Master Calligrapher: Haji Noor Deen,” http://www.hajinoordeen.com/index.html.

Jonathan Lipman, Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998).

[1] Muslims first settled in China during the earliest days of Islam, and over the centuries communities developed in every region of China. According to the 2010 Chinese census there are over 20 million Muslims in China, living in every major city. Of China’s officially recognized 55 minority groups, 10 are predominantly Muslim. The largest group, estimated at around 10 million, is the Hui. The next largest group consists of the Uighurs, a Turkic people who live primarily in Xinjiang, a province in northwest China, and speak a Turkic language. Most of the other eight groups are also located in northwest China and speak their own language (including the Kazakh, Salar, Tajik, and Kirghiz). The Hui are unique in that they are the descendants of Muslims from Central Asia, the Middle East, and Persia who settled in China from the Tang to Yuan dynasties.

[2] Lawrence E. Butler, “Mosques and Islamic Identities in China,” Middle East Institute, April 2, 2015, http://www.mei.edu/content/map/mosques-and-islamic-identities-china.

[3] For a detailed history of these periods in the history of Hui communities in China, see David Atwill, The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856-1873 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005) and Jonathan Lipman, Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998).

[4] Niche denoting the direction of the Ka‘ba.

[5] If any readers have seen, or know of, similarly engraved funerary biers, in China, or any other Muslim communities, please contact the author: armijo@gmail.com.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.