Most of the numerous articles written about the ongoing revolutions in the Middle East have focused on their political and/or economic causes and likely consequences. However, environmental and natural resource-related issues, which are also at the center of these revolutions, have received little or no attention.

This essay discusses the salience of such issues in the 2011 Middle East revolutions, with particular reference to the case of Egypt. More specifically, it argues that environmental and resource-related issues were “hibernating phenomena;” that is, they were among the underlying causes of the conflict with Egypt’s ruling establishment.

Roots of Popular Revolution: The Case of Egypt

The Middle East uprisings in general and the revolution in Egypt in particular stemmed from the anger of ordinary people. The January 25 Revolution in Egypt was initiated by well-educated youth, and not, as might have been expected, by the poor or by the masses of unemployed. Yet, although youth were the vanguard of the uprising in Egypt, the overwhelming majority of the population supported their demands. Moreover, contrary to predictions, political rather than economic grievances were at the forefront of the protesters’ demands.

During the January 25 Revolution, protesters raised banners and chanted slogans cast mainly in political terms, such as “Down, down Husni Mubarak,” “Leave, leave Husni Mubarak,” “Get out,” “Game over,” and “People want freedom.” The key slogan of the revolution has been, “The people want the downfall of the regime.”

How, then, to explain the uprising? In seeking to ascertain the direct and indirect reasons for it, one must be careful to avoid conflating the triggering events, the tools employed, and the underlying causes.

There were several events that can be considered as triggers for the Egyptian Revolution:

- 1. The death of the young internet activist, Khaled Mohamed Saied.

- 2. The death of the young Islamic activist, Sayed Belal.

- 3. The bombing of the Kedeseen Church in Alexandria on January 1, 2011.

- 4. The inspiration provided by the Tunisian Revolution (December 2010–January 2011).

To be sure, social networking media, including Facebook and Twitter, played a key role in the Egyptian Revolution. However, it is important to emphasize that social networking is a communications tool, not in itself a triggering event or an underlying cause of revolution.

In fact, there were a multitude of underlying causes, or what might be called “hibernating phenomena,” that led to the conflict with the ruling establishment in Egypt. They include:

- 1. Continual elections fraud.

- 2. Manipulation of laws.

- 3. Massive theft of the nation’s financial and natural resources.

- 4. Emergency law.

- 5. Police brutality.

- 6. The Mubarak regime’s foreign policy orientation, especially its policies toward the West and Israel.

- 7. Corruption and bad economic, social, and political conditions.

- 8. The anticipated transfer of power to the President’s son, Gamal Mubarak.

The Egyptian Revolution and the Environment

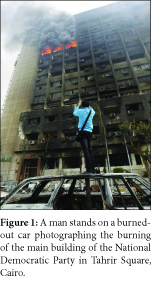

The most obvious connection between the Revolution and the environment was the adverse impact on the man-made sphere and biosphere caused by the burning or destruction of a number of buildings and other property during the protests (see Figure 1).[1]

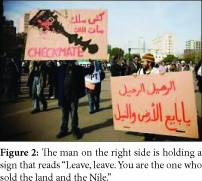

Yet, there were many less obvious and arguably far more meaningful connections. For example, some signs displayed during the protests, such as the one depicted in Figure 2[2] below, indicate that some believed that the ruling regime was culpable for squandering the country’s precious natural resources.

Indeed, environmental and resource-related issues were at the very core of the Egyptian Revolution, as many of the policy decisions and their consequences of the ruling regime had come to fuel popular discontent.

The export of natural gas, especially the unusually favorable terms by which gas was sold to Israel, is a case in point. In 2004, Egypt agreed to supply Israel with natural gas at approximately one-third of the international price for a period of 30 years. This agreement angered many petroleum experts, who argued, among other things, that the gas should be used to meet Egypt’s own domestic consumption requirements. Gas exports to Israel continued despite these objections and the fact that opponents managed to obtain a court decision in their favor. This is considered an environment-related issue, as one can see from the following sign (Figure 3)[3] raised before, during, and after the Revolution saying: “No for gas setback. Stop Egyptian natural gas exports. Stop the bleeding of Egypt’s natural resources.”

During and after the public protests that brought down the regime, protesters included environmental and resources-related issues among their catalogue of grievances, loudly proclaiming, “No” to carcinogenic pesticides and fertilizers, “No” to polluted water resources, and “No” to the bulldozing of farmland.

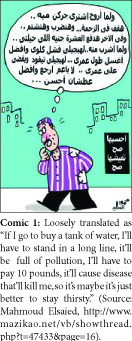

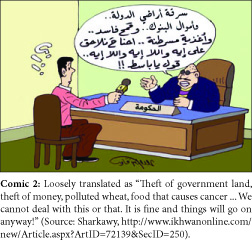

The following two caricatures show clearly that such issues were indeed “hibernating phenomena” — underlying causes of the revolution.

Two of the key slogans of the revolution were: “The cancer is everywhere, and the gas is sold for free” and “Husni Mubarak, you agent, you sold the gas and (only) the Nile is left (to be sold).” Of the many jokes circulating during the Revolution, some referred to the impact of the regime’s policies on the environment: “Our Prime Minster’s name is Nazeef (i.e. clean) and pollution is killing us all!”

It is revealing that, when the uprising ended, the same people who had been demonstrating for 18 days immediately started to clear Tahrir Square of trash and debris (Figures 4 and 5).[4] Similar clean-up operations occurred in cities throughout Egypt.

The link between the revolution and the environment can also be seen in the actions taken by demonstrators. Immediately after the regime was ousted from power, youth campaigns were launched to clean, paint, and plant in streets and cities across the country. These and other acts of collective “environmental citizenship” were very important. They sent a clear signal to the authorities, challenging the self-interested rational actor model that had pervaded official thinking and policies for decades and articulating the people’s wider social interests and concerns.

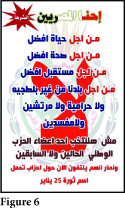

Interestingly, the second and third lines of a flyer circulated during the run-up to the March 19 constitutional referendum (Figure 6)[5] that asked people to vote “No” also mentions a better quality of life and better health.

During the celebrations of the success of the Revolution, signs were displayed (Firgure 7)[6] asking people not to dispose of garbage in the streets and to observe traffic signals.

The list of demands issued on April 8, “The Friday of Cleansing,” included several directly related to the environment:

- 1. Change old governors, break up local councils, and abolish the National Democratic Party.

- 2. Investigate the issue of looting of state land.

- 3. Investigate the issue of carcinogenic of pesticide.

- 4. End the corrupt process of privatization of the public sector.

- 5. Punish the killers of the demonstrators and those who poisoned the food and water and destroyed human health.

The common discourse was replete with expressions such as “the people want to achieve reconstruction and sustainability,” instead of merely “people want to overthrow the regime.” On the occasion of Sham Al Naseem Day (Easter), on April 25 — exactly three months after the January Revolution — the literal and the figurative merged into one, as I heard nearly all people exclaiming, “This is the first time we can smell fresh clean air!”

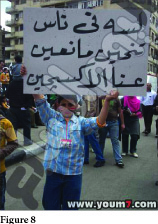

Nevertheless, the road to sustainable development has not been cleared of all obstacles. One such obstacle is residual resistance to positive change, as indicated in a sign which reads, “Still there are clumsy people who are keeping fresh air away from us” (Figure 8).[7] Another is the sheer number and complexity of the environmental and natural resource challenges facing the country, including those related to the theft of the Pharos monuments and Alsakury gold mines, and, most significantly, the Nile River. The Revolution has made the enactment of policies conducive to sustainable development possible, though not inevitable.

Conclusion

It is clear that environmental issues and negative environmental impacts were among the underlying causes of the Egyptian Revolution. One of the important lessons of the Egyptian experience is that the Arab world needs to carry out continuous green projects that motivate individuals, especially youth, to serve and protect their countries. In this regard, it is the task of the international community through international aid, investment, and other forms of cooperation to support local efforts to pursue sustainable development.

[2]. Flickr user 3arabawy, http://www.flickr.com/photos/elhamalawy/5423036364/.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.