Converging Lines: Tracing the Artistic Lineage of the Arab Diaspora in the U.S. is on display at the MEI Art Gallery through Nov. 17, 2021. For more details, please visit the website.

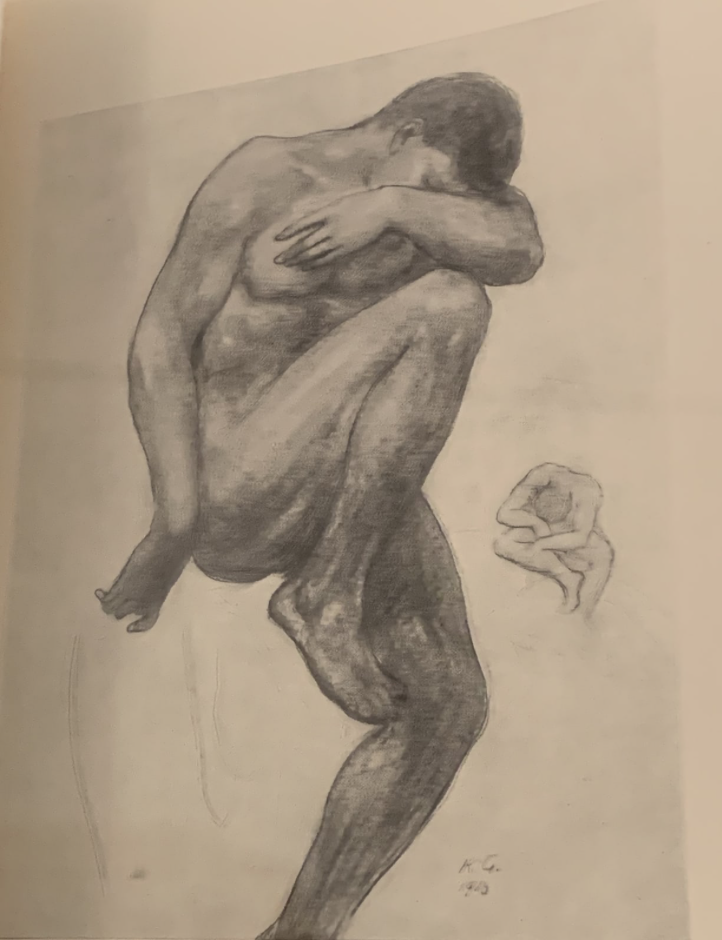

Converging Lines: Tracing the Artistic Lineage of the Arab Diaspora in the U.S. seeks to situate Arab and Arab American artists within the larger history of American art while emphasizing the rich history of cultural production that has come from the larger Arab American community. Artists identifying with the Arab diaspora in the U.S. have been contributing to the progression of American art since the early 1900s, beginning with Kahlil Gibran, whose paintings and drawings were part of the international Symbolist movement that used subjectivity as a means of tapping into the psychological underpinnings of life at the turn of the century. Gibran was active in artistic circles in both Boston and New York and central to a group of writers who saw themselves as the link between developments in American literature and the changes that were occurring in the literary scenes of the Arab world. This emphasis on a state of in-betweenness — of mediating two worlds and moving effortlessly between them — has continued with subsequent generations of Arab American artists.

As an artist and a writer, Gibran was one of the earliest proponents of Arab American identity. In his 1931 poem, To Young Americans of Syrian Origin, he addresses Arab American youth, urging them to embrace a hyphenated identity, to take pride in their ethnic and cultural origins, but to view themselves as “deeply rooted here” and as “contributors to this new civilization.” Gibran’s sense of assuredness in this newly formed identity was in part due to his own place in the sizeable and diverse immigrant communities on the East Coast that he called home. In New York, he actively exhibited at a time when the city was becoming a hub for international art and the center of American art. Artists belonging to the Arab diaspora today live and work throughout the country, from New York to Hawaii, and are often shaped by their immediate environments, especially the local art scenes to which they contribute. Looking at the personal histories of these artists, the range of their works, and the trajectories of their careers reveals a chapter of American art history that has yet to be fully documented.

The artistic output of the Arab diaspora in the U.S. is American art. This cannot be overstated. In Converging Lines, we find artists like Etel Adnan, whose vividly painted landscapes of her forever muse, Mount Tamalpais, capture the light and physicality of California’s coastal terrain and the northern California penchant for a type of mysticism that views nature and the universe as main protagonists. Adnan’s creative origins as an anti-Vietnam war poet amidst the anti-war movement in San Francisco and Berkeley, and later as a member of a small circle of artists in Marin County make her a quintessential Bay Area artist. Yet recognition of her place in this history has been slow to emerge. Today, we revere her as an elder Arab artist whose unwavering political convictions and reflective and empathetic work describe the shortcomings of the post-colonial era in the Arab world. But she also has a place in the history of West Coast art as a colorist and a landscape painter, except that in Adnan’s paintings there are no illusions of the open, uninhibited space that we find in the images that have historically represented California, but rather an underlying sense of grief and mourning as the mountain rises and the ground below seemingly retreats, a body inhaling to restore itself and exhaling in order to survive.

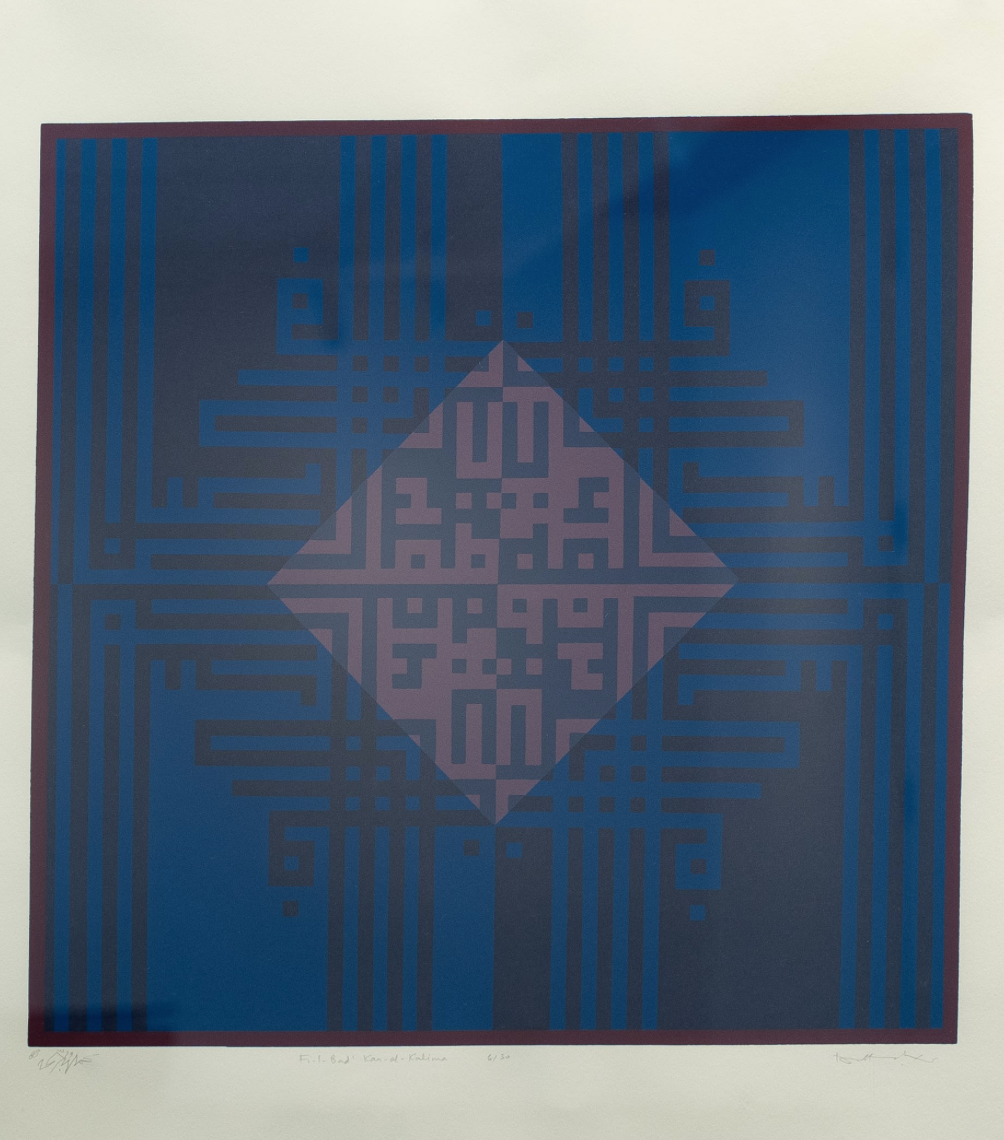

Adnan lived on the West Cost for decades until she eventually settled in Paris. The late painter and printmaker Kamal Boullata had a similar path in the second half of the 20th century, arriving in Washington D.C. in the 1960s to attend grad school at the Corcoran School of Art. Boullata was active in the American capital for nearly three decades, a period of his life and career that has unfortunately only been footnoted. He was associated with one of the first art spaces dedicated to Arab art in the U.S., Alif Gallery in Washington D.C., and was a driving force of its programming in addition to being an exhibiting artist. He embraced new trends and responded to the developments in art that were taking place in the city. In the mid-1960s, for example, two significant exhibitions of artists belonging to the Washington Color School were held at the Corcoran School of Art, which he certainly must have seen as a graduate student. Reviewing his work from his time in the U.S., we see that Boullata adopted the deep saturation of color that distinguished this movement of color field painting while continuing to develop the innovations in geometric abstraction that he would later become known for, which were informed by the rich cultural history of his native Jerusalem. Boullata openly, and defiantly, incorporated the Arab/Islamic identity of the ancient city in works that engaged distinctly American experiments in contemporary painting, and for that he should be remembered as an artist who honored tradition but valued experimentation and was consciously working against the American political current, a rebel and shapeshifter.

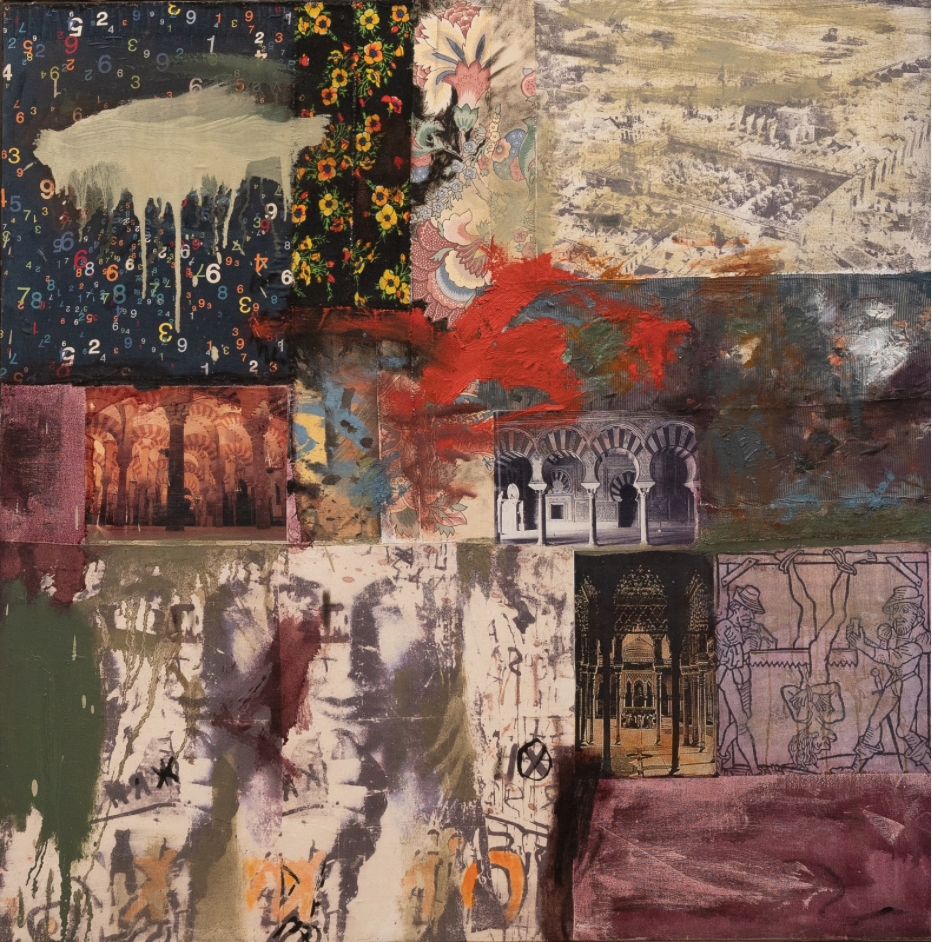

New York-based painter and master printmaker Mohammed Omar Khalil belongs to the same generation of artists, immigrating to the U.S. around the same time. Khalil’s gray scale palette is said to reflect the terrain of his native Sudan, yet in the paintings shown in Converging Lines, collaged found images and fabric and expressionist swaths of paint describe America’s colonial history and the social inequities, pain, and erasure that were built into its foundation. Among the collaged images in 1492 (2010), for example, is a historical illustration of the torture techniques that Spanish conquistadors used on indigenous people in the Americas. Images of Islamic Spain are scattered throughout the composition while areas of emphatic brushwork simulate chaos and violence. Here, one empire blurs into the next and results in more human suffering. Khalil’s palette, although muted, or grayed, is also indicative of the unshakeable legacy of Abstract Expressionism that shaped painting in New York for decades. It can also be interpreted as a reflection of the grit and grime of New York streetscapes, the patina of struggle and fight for survival that the city demands from its inhabitants. Looking at Khalil’s work, one can see hints of the experiments that were taking place in Khartoum in the early 1960s, when he was studying art there, yet his layering of various elements and use of select images to build a cohesive narrative are indicative of the painting and printmaking techniques that were simultaneously emerging in New York with artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Khalil’s aesthetic oscillates between the city of his youth, and the memories of that place, and the psychosocial dynamics of the metropolis that he has called home for over 50 years. Gibran would be proud.

Maymanah Farhat, an independent curator and writer, is the curator of the show Converging Lines: Tracing the Artistic Lineage of the Arab Diaspora in the U.S. Her art historical research and curatorial work focus on underrepresented artists and forgotten art scenes. The opinions expressed in this piece are her own.

Top photo by MEI

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.