The Bethany Beyond the Jordan baptism site, where Jesus of Nazareth is believed to have been baptized by John the Baptist, is adorned with bright green acacia trees known for withstanding intense heat. Also scattered throughout the area, nine kilometers north of the Dead Sea in the Jordan Valley, are feathery tamarisk plants with needle-like leaves. These shrubs hold biblical significance: According to the Bible, they were planted by Abraham, sought for solace by Saul, and provided rest for fallen warriors. To this day, these plants, along with trees and thickets of reeds, permeate the landscape, creating a striking contrast against the vast and barren desert.

In early June this year, tourists and pilgrims, led by a guide, walked in groups, pausing at the baptism site to observe the distant pillars and faded mosaics. Before reaching the river, the group visited a small Greek Orthodox church with intricate murals and aqua-blue stained glass windows. Spanish tourists, dressed in white gowns, immersed themselves in the Jordan River (now much reduced), reenacting biblical scenes while being observed by Jordanian soldiers.

An elderly woman stared at the river; her emotions overwhelmed her as tears streamed down her cheeks. A young Jordanian man from the tour turned to his friends and quietly said, “It is to them what Mecca is to us.”

Archeological discoveries and biblical connections

Formerly filled with thousands of landmines, the area has evolved into a treasure trove of archaeological discoveries. Since the signing of a peace treaty between Jordan and Israel in 1994, extensive excavations have unearthed remnants of churches, baptismal pools, water channels, and caves, emphasizing the historical significance of the region as a pilgrimage site dating back to the 4th century CE.

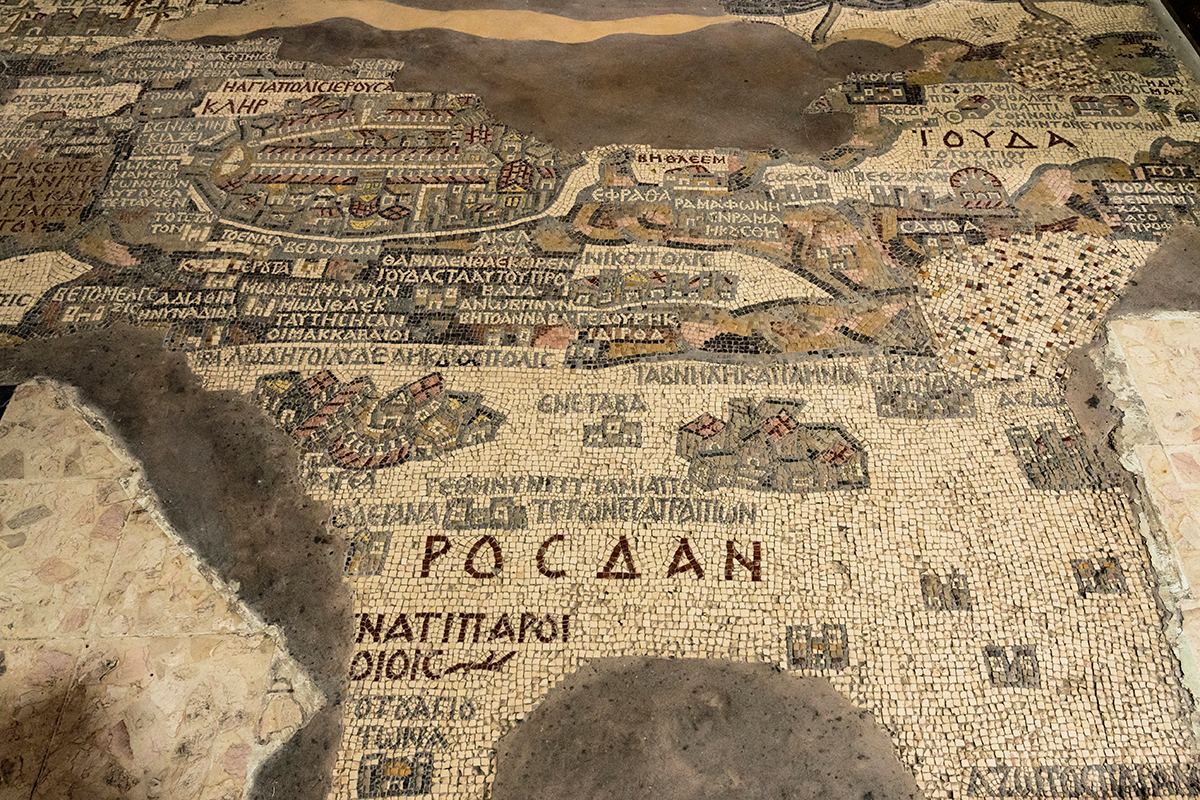

The location of the actual baptism site remained a mystery until clues, left behind by monks and local inhabitants, were discovered. In 1884, the ruins of an old Byzantine church were cleared in the ancient town of Madaba, southwest of Amman. It was during this excavation that the oldest mosaic map of Jerusalem and the Holy Land was discovered. It contained indications of the site, in present-day Jordan, where Jesus was believed to have been baptized. It has also gained recognition from archaeologists, researchers, popes, and the United Nations.

This location, surrounded by ancient pillars and churches that have stood since the 5th century CE, is one of the most sacred Christian sites, along with the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In 2015, it was designated as a World Heritage Site.

Situated to the east of the river is the Hill of Elijah, a site where religious figures and followers believe Jesus revealed himself to his apostles Peter, James, and John. The area also encompasses the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. In 1991, a cave was discovered in the hills. It was identified as the ancient site of Zoar, the city where it’s believed Lot and his family took refuge during the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. Nine religious organizations will be granted the opportunity to build a place for receiving pilgrims at the baptism site.

Tourism and development efforts

The Jordanian government’s efforts to attract tourists to the baptism site have at times been met with a mixed reception. In 2017, an advertising campaign was launched with the slogan, “For God’s sake, visit.” While the campaign resonated with the Lebanese as a heartfelt appeal, it was viewed as flippant by some Jordanians. More recently, the country’s tourism sector faced another setback due to the enforcement of stringent coronavirus measures, effectively prohibiting visitors.

The tourism sector in Jordan contributes approximately 20% of GDP. In 2019, over 5 million people visited Jordan; during the first quarter of 2023, more than 1.4 million tourists were recorded. According to the Ministry of Tourism, around 85% of visitors to Jordan come for its history and culture, with religious sites like Mt. Nebo and the baptism site ranking just below popular destinations such as Petra, Jerash, and Wadi Rum. Even so, the country faces tough competition in attracting tourists compared to its neighbors, including Israel. More recently, Saudi Arabia is making a major push to develop its tourism sector with the aim of reaching 100 million visitors per year and making tourism its second-largest revenue source by 2030.

The baptism site attracts a diverse range of visitors, with Europeans comprising the majority, followed by 24% from the United States, 7% consisting of Jordanians and visitors from Arab countries, and the remaining 9% coming from Africa and East Asia. With the lifting of travel restrictions in Jordan and elsewhere, a comprehensive marketing campaign by the government targeted Europe and Gulf countries through advertisements in train stations, shopping centers, and online.

Since then, the baptism site has experienced an upsurge in tourist arrivals, including a recent visit by Oprah. She shared a photo of herself with her 22 million Instagram followers, standing on a step of the site that is usually inaccessible to the public. By the end of this year, visitor numbers are expected to reach 200,000, doubling the figures from previous years, including before the pandemic.

All this is now set to change still further. In 2021, the Jordanian government allocated a 338-acre plot adjacent to the baptism site for development. After undergoing multiple drafts, the master plan was recently submitted to UNESCO. “We want to make sure this place is preserved for centuries to come,” said King Abdullah during an interview with CNN in December last year. “I think it [all] started here and it tells the story of Jordan throughout the ages.”

The plan outlines a six-year, $300 million project. It envisions a village offering amenities such as hotels, an amphitheater, glamping facilities, a museum, and hospitality services. The plan also includes a designated area for spiritual ceremonies, aiming to further attract pilgrims.

“The aim is to create a world-class destination for religious tourism,” explained Kamel Mahadin, the main architect behind the designs. “The place will be an educational and historically significant Christian pilgrimage site.”

This upsurge of interest coincides with a significant decline in the Christian population in the Arab world. In countries such as Syria and Iraq, ongoing conflicts have had a detrimental impact on Christian communities. In other countries, like Jordan, the challenging economic conditions and the allure of better opportunities elsewhere have played a role in the decreasing numbers.

During the interview with CNN, King Abdullah expressed concern about the potential consequences of the declining numbers: “If we don’t have any Christians in the region, I think that is a disaster for all of us. They are part of our past, they are part of our present, and they must be part of our future.”

Challenges and conservation

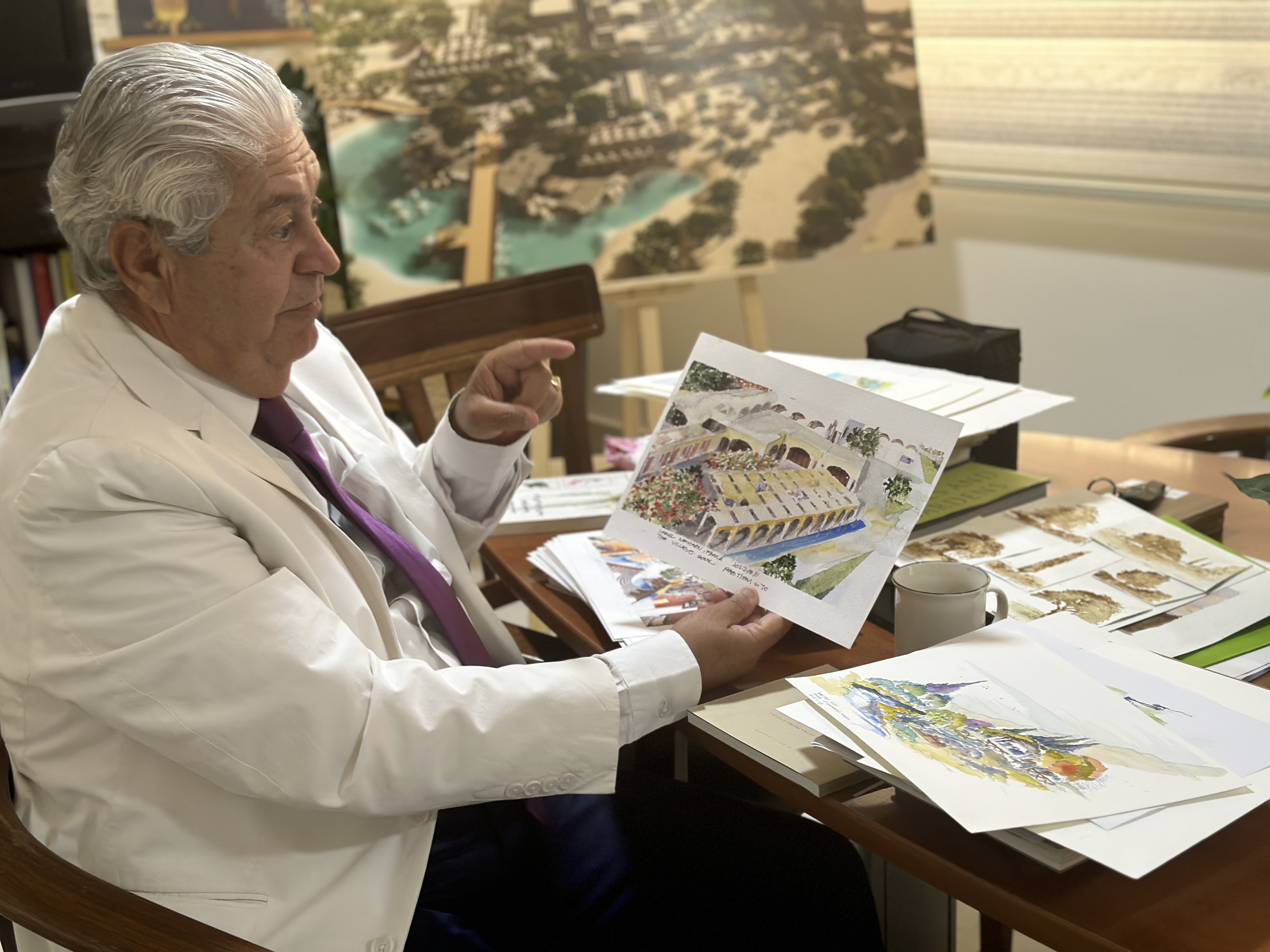

Kamel Mahadin’s office in Amman is filled with posters, notebooks, and digitized models of the baptism site plans. He says he drew inspiration from ancient cities like Bethlehem, Jerusalem, and Karak in Jordan, incorporating elements from these historical locations into his designs.

Together with his son and fellow architect Yazan, he still frequently visits the baptism site and makes presentations to visitors and high-level officials. Seated on his desk, Kamel revealed a collection of colored sketches he made depicting native plants, flora, and wildlife that characterizes the baptism site and surrounding area.

The project includes the creation of agricultural parks, a bird sanctuary, and shops and farms that will offer visitors a taste of local cuisine. It will also showcase vegetation of religious importance, such as palm and olive trees.

“We’re not here to uproot anything,” said Yazan. “The plan will add to the native vegetation and create a sustainable ecosystem.” He noted that between 60% and 70% of the land will be designated as a farm development area. The project, adjacent to the baptism site itself, prioritizes sustainable practices, highlighting the importance of water recycling and integrating solar panels to harness renewable energy.

While many have applauded the proposal, there are concerns that overcommercialization and infrastructure development could potentially compromise the site’s spiritual and historical ambiance. But Jordanian authorities and architects argue that the final design of the development is both environmentally friendly and will have the infrastructure needed to support 1 million pilgrims and tourists a year.

“The overall theme and feel is going back 2,000 years in time,” said Samir Murad, a former Jordanian labor minister who is now chairman of the board of trustees of the baptism site development zone. The project, he said, will respect the historical significance of the place and incorporate earth-tone colors and white domes, drawing inspiration from biblical references: “It will allow visitors to feel the wilderness, spirituality, and offer an opportunity for reflection.” He added that the development would include trails of up to three miles, a botanical garden, and tree houses.

The concept aims to create a two- to three-hour visit that encourages people to engage with the locals and consider staying longer, explained Murad. The plan, if implemented, would revitalize the area and address the urgent need for job creation in the local community, which is suffering from high unemployment rates. Nationwide, nearly half of Jordanian youth are unemployed, and almost a quarter of the country’s population lives below the poverty line.

A board and an advisory committee that includes experts and stakeholders have been assembled to oversee the project’s implementation and decision-making process. The initial phase centers around government-funded infrastructure development for drainage, water, and electricity. Subsequently, the project will seek funding from a sustainable development fund in collaboration with the United Nations. Funds will also be sought from philanthropists and through investment opportunities such as land leases and revenue sharing. For this year, members are hoping to begin with farming and, by next spring, with glamping facilities, according to Samir Badran.

However, both the master plan architects and committee members harbor concerns about the project, primarily focusing on the daunting challenge of raising sufficient funding and the practical difficulties of implementation, including how to accommodate five times the current number of visitors to the site. But the project’s fate is not solely dictated by financial constraints and logistical hurdles; political dynamics and environmental considerations also loom large.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Evident along the parched river’s edge were deep dry creases etched into the sand, highlighting the arid conditions. The level of the Dead Sea has been dropping by one meter each year, causing sinkholes and other major problems for the agricultural sector. The continuous diversion of water from the Jordan River is contributing to its contraction, which is worsened still further by climate change and rising temperatures.

Today, the Jordan River’s flow is less than 10% of its historic average. Around 37% of Jordan’s water supply comes from surface water resources, primarily the Jordan, Zarqa, and Yarmouk rivers. Jordan’s access to these rivers is being impacted by the lack of regional environmental cooperation and the diversion and over-pumping conducted by Israel and Syria, leading to the rivers’ depletion.

Jordanians, Palestinians, and Israelis have previously discussed a mega-project to build a canal from the Red Sea to feed the Dead Sea. The surface of the Dead Sea is 430 meters below sea level, so the project could also exploit this difference in elevation to generate electricity. After being talked about for years, an agreement on the canal was signed in 2013 with the aim of helping to alleviate Jordan’s severe water shortage while helping to replenish the fast-shrinking Dead Sea. Ultimately, however, the project was abandoned due to bureaucratic difficulties, financing challenges, and environmental objections.

Elias Salameh, a hydrologist and leading expert on water in Jordan, points out that the severity of water scarcity and climate change is compelling regional countries to initiate fresh and increasingly urgent discussions regarding strategies to protect the Dead Sea and, consequently, the Jordan River. “All parties involved, including the Jordanians, Palestinians, and Israelis, have much at stake in the face of the potential loss of the Dead Sea and the water shortage challenges we are facing.”

In the Mahadins’ office, meanwhile, Kamel carefully sifts through the papers on his desk. He uncovers some conceptual watercolor paintings from his pile of sketches, showcasing the pilgrimage village, path walk, bazaar, and museum. “Our vision,” he said, “is that this is the lowest point on Earth, yet it’s closest to God.”

Rana F. Sweis is a freelance journalist covering political, social, and refugee issues in the Middle East. She is the author of Voices of Jordan (Hurst Co.), a nonfiction book about modern-day life in Jordan. She holds an MA from George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management.

Main photo courtesy of the author.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.