Originally posted August 2010

The literature on cooperation on readmission tends to assume that the agreements reached between destination and source countries are characterized by unequal relationships, for the parties involved do not share the same interests and implications in the cooperation.[1] A large body of literature has argued that developing countries cannot make meaningful choices because they are controlled, directly or indirectly, by external influences.[2] The dominant perspective in the scholarly debate is that the externalization of migration policies — defined as the process whereby the place where travelers are controlled shifts “from the border of the sovereign state into which the individual is seeking to enter to within the state of origin”[3] — is based on the subordination of the South.[4] In the specific European context, some scholars have suggested that by involving migrant-sending countries in the “struggle against migration,” the EU is devolving some of its responsibilities to them and, by implication, moving the complex task of managing migration outside the rule of law.[5] The corollary of this position is that the EU migration policies strengthen mainstream realpolik accounts of power relations, for they continue to weaken the South. In this context, Keohane’s work on reciprocity and “relations among unequals” is particularly relevant for understanding emerging relations of power between the EU and its neighboring countries.

Within this overall trend, the non-standard agreements linked to readmission between Italy and Libya are insightful. Since it is a pioneering and relatively advanced example of cooperation in the European context, the issue of whether it is based on unequal reciprocity appears to be particularly pertinent. Therefore, the question that I shall address in this chapter is whether the Italian-Libyan agreements linked to readmission can be treated as an example of relations among unequals. In other words, does the selected case study reflect what Keohane calls “reciprocity in unequal obligations”?

This chapter is divided into four sections. First, I illustrate Keohane’s argument and define the relevant terminology. Second, I present a brief historical excursus of the Italian-Libyan agreements in order to set the scene for the third section, which is concerned with the types of agreements as such. In providing an historical overview of the “return flights” between October 2004 and March 2006, I will also elaborate on the criticisms that were leveled by a number of different international organizations against Italy and Libya.[6] The fourth section applies the concepts of reciprocity and relations among unequals, to the empirical analysis. By focusing on the costs and benefits in the Italian-Libyan patterns of cooperation on readmission in wider negotiations on migration, I analyze the overall bargaining dynamics and explore the extent to which there are power disparities. In the final section I conclude that the agreements epitomize a relation among unequals for Italy has higher obligations and costs than Libya. I will also argue, however, that this unbalance is recast in the overall bilateral agreements on migration that are best defined by Keohane’s notion of “diffuse” yet still unequal reciprocity.[7]

Before embarking on these tasks, it is important to stress the limitations of this chapter. First, I take great liberty in applying Keohane’s concept of reciprocity to a bilateral agreement. His analysis concentrates on multilateral frameworks. However, I have taken the view that utilizing the concept of reciprocity in this case study may help us appreciate the multifaceted nature of state interactions in relation to evolving migration dynamics. Second, in this chapter I refer to the Italian-Libyan non-standard agreements as the sum of the informal discussions on repatriation flights from Italy to Libya. This utilization transcends the standard meaning, for it does not imply that Italy and Libya have formally signed a standard readmission agreement in the manner that other European and non-European countries have done with migrant-sending countries. Third, the empirical analysis centers on charter flights. These took place between 2004 and 2006 and were aimed at removing unauthorized aliens. In the conclusion I will link such agreements to the development in the collaborative arrangements in 2009.

Approaching Reciprocities

Keohane identifies two interrelated types of reciprocity:

I…use specific reciprocity … to refer to situations in which specified partners exchange items of equivalent value in a strictly delimited sequence. If any obligations exist, they are clearly specified in terms of rights and duties of particular actors. This is the typical meaning of reciprocity in economics and game theory. In situations characterized by diffuse reciprocity, by contrast, the definition of equivalence is less precise, one’s partners may be viewed as a group rather than as particular actors, and the sequence of events is less narrowly bounded. Obligations are important. Diffuse reciprocity involves conforming to generally accepted standards of behavior.[8]

Put another way, while the first type refers to the interaction on one specific issue, the second refers to the ongoing discussion across a range of different issues for the sake of continuing satisfactory overall results. Depending on the extent to which exchange is equivalent, it is possible to identify three kinds of reciprocity. For purposes of clarity, I distinguish them in the following manner: (1) full reciprocity, (2) unequal reciprocity, and (3) non-reciprocity.[9] As concerns the first one, international relations literature has elaborated extensively on reciprocity and, more often than not, has defined it as an equivalent exchange. In quoting Gouldner, Keohane makes clear that “reciprocal behavior returns ill for ill as well as good for good: ‘people should meet smiles with smiles and lies with treachery.’”[10] However, he also observes that reciprocity applies to situations of “rough equivalence”:

Reciprocity can also characterize relations among unequals, for instance, between a patron and his client, when there is little prospect of equivalent exchange. Patron-client relationships are characterized by exchanges of mutually valued but non-comparable goods and services.[11]

This second type of interaction refers to “reciprocity in unequal obligations” that is the “really distinctive feature of European vassalage”.[12] By contrast, “when we observe one-sided and unrequited exploitation, which cannot under any circumstances be considered an exchange of equivalents, we do not describe the relationship as reciprocal”.[13] Situations that lack a “rough balancing out” cannot be considered reciprocal and are defined in this chapter as non-reciprocal.

To assess the extent to which relations are based on reciprocity, Keohane examines obligations involving the duties of both parties. In a reciprocal interaction, “people should help those who have helped them, and people should not injure those who have helped them.” These norms “impose obligations.”[14] Obligations are important since they are indicators of the extent to which there is conformity to generally accepted standards of behavior.[15]

The next section examines the nature of reciprocity in the Italian-Libyan bilateral agreements linked to readmission and wider negotiations on migration by assessing the obligations of each party. Which of the three scenarios explained above best capture their interaction: full reciprocity, unequal reciprocity, or non-reciprocity?

Background to the Agreements on Migration between Italy and Libya

The discussions between Italy and Libya on migration controls started in the late 1990s. On July 4, 1998, a “Joint Communiqué” was signed. The significance of this agreement derives from Italy’s formal acknowledgment of the suffering caused during the colonial period. In the period following the signing of the agreement, a number of meetings between Italian and Libyan authorities on migration-related issues, among other things, took place. This intense discussion led to the signing of the Memorandum of Intent in December 2000, which addressed drug-trafficking, terrorism, organized crime, and illegal migration. The agreement became effective after its ratification in the Italian Parliament on December 22, 2002.[16]

Between 2000 and December 2007, no formal agreements on migration were signed between the two countries. Nevertheless, the discussions on migration continued, and a set of concrete actions were implemented. Of particular relevance are the measures informally agreed, in Tripoli on July 3, 2003. Reportedly, the Italian Minister of the Interior and the Libyan Justice Minister, Mohammad Mosrati, reached an agreement involving, among other things, the exchange of information on migrant flows and the provision to Libya of specific equipment to control sea and land borders.[17] Two more recent agreements also deserve mention. On December 28, 2007, the two countries signed an agreement on the joint patrolling of coasts, ports, and bays in northern Libya to prevent people-smuggling.[18] On August 30, 2008, in a tent in Benghazi, Silvio Berlusconi and the Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Al Qadhafi signed an historic agreement, according to which Italy will pay $5 billion over the next 20 years, nominally to compensate Libya for the “deep wounds” of the colonial past.[19] The agreement was the culmination of a tortuous ten-year long history of diplomatic exchanges, which included a number of formal and informal cooperative arrangements on a variety of issues, such as migration, culture, colonial issues, and joint-business ventures.

Overall, even though neither the Italian nor the Libyan government has disclosed detailed information on the measures agreed and implemented, it is possible to identify the main joint measures implemented so far:

1) Reception centers funded by Italy in Libya: Italy has financed the construction of camps intended to host migrants. On this issue, a statement by Undersecretary of the Interior, Marcella Lucidi, in July 2007 revealed that one center in Gharyan had already been handed over to the Libyan authorities for police training purposes. The second center in Kufra was in the process of being built and was intended to provide health support to migrants. Lucidi also made clear that no other centers were to be built.[20] Importantly, during interviews with Libyan and Italian officials in Tripoli between 2007 and 2008, I was told that the centers were no longer intended for confining “illegal” foreigners, but rather for police training and providing humanitarian assistance;

2) Repatriations from Italy: As I will illustrate in detail, Italy financed the removal of over 3,000 migrants to Libya between October 2004 and March 2006;

3) Repatriations from Libya: Italy has been financing flights to repatriate unauthorized migrants from Libya to third countries.[21] It is uncertain whether this practice is still in force;

4) Coordinated Patrol Systems: Italy has repeatedly asked Libya to participate in joint patrols in the Mediterranean. Libya had refrained from taking part[22] until May 2009 when joint patrols resumed;[23]

5) Provision of Equipment: the non-standard bilateral agreement signed in July 2003 included, inter alia, assistance to strengthen the Libyan authorities’ ability to patrol land and sea borders. For example, on May 2005, the Italian Ministry of the Interior agreed to spend €15 million over three years to equip the Libyan police with the necessary means to combat irregular migration;[24]

6) Training program: the Italian-Libyan agreements signed in 2000 mentioned the cooperative arrangements to train police officers. Since then, the Italian government has co-funded and managed a range of training courses for Libyan police staff;[25]

7) Exchange of intelligence information: a critical aspect of the bilateral collaboration focuses on the exchange of information on smuggling organizations. For this purpose, a representative of the Italian Ministry of the Interior is based in Tripoli and a liaison officer from the Libyan Ministry of the Interior is likewise located in Rome[26];

8) Push-backs: According to the available records, this measure was first implemented between May 6−10, 2009 when 471 migrants intercepted on international waters were shipped to Libya by Italian police.[27] On July 1, 2009, 89 other foreign nationals were “pushed back” to Libya.[28] Importantly, this measure is not to be confused with joint patrolling since it does not appear that Libyan officials were aboard the vessels;

9) Cooperation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM): The IOM has implemented projects on migration co-funded by the Italian government. In particular, as part of the project “Across Sahara”, the IOM has collaborated with the Italian scientific police to organize activities such as workshops for police staff from Libya and Niger.[29]

In keeping with the aim of this chapter, I now turn to a detailed analysis of the non-standard agreements.

Agreements Linked to Readmission

The practice of readmitting unauthorized migrants to their alleged countries of origin has been widely employed by Italy as well as other European and non European countries.[30] To date, Italy has signed readmission agreements with over twenty countries, including Albania, Algeria, Croatia, Georgia, Morocco, Moldavia, Nigeria, Serbia, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Tunisia, Cyprus, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovenia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania.[31]

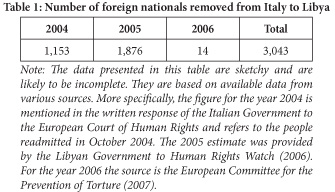

Repatriations represent a critical aspect of the Italian-Libyan collaboration on migration. Between October 2004 and March 2006, Italy organized charter flights from Sicily to Libya, transporting migrants who had recently arrived in Italy from the North African country. For our purposes, a historical excursus of these measures is instructive.[32]

From September 29 to October 3, 2004, 1,728 undocumented migrants reached the island of Lampedusa on 20 vessels that were sighted and rescued by the Italian police forces. On October 1, the Italian authorities ordered the removal of 90 foreigners from Lampedusa to Libya. The following day, three flights brought over 300 migrants and asylum-seekers to Tripoli. On October 3, two special Alitalia flights and two military planes deported another 400 people, and four days later, military planes removed still more.[33] As the Italian Government stated in its response to the appeal before the European Court for Human Rights, between September and October 2004, “1,153 foreign nationals — most of them of Egyptian nationality — were removed to Libya on 11 charter flights”.[34] Before the Collegio per i Reati Ministeriali (i.e., Italian Ministerial Tribunal), Alessandro Pansa added that the flights were directed to Albeida Airport in Libya so that the migrants could be transferred to Egypt.[35]

A few months later, a second wave of repatriations took place. On December 20, 2004, an Italian police press release reported that 200 unwanted Egyptian migrants coming from Libya had boarded a plane at Crotone Airport to Tripoli. According to the same source, these measures exemplified “the positive collaboration with Libyan authorities”.[36]

A third series of repatriations was undertaken in March 2005. Between March 13−21, 1,235 migrants arrived in Lampedusa. Of them, 421 requested protection and were transferred to Crotone. Another 494 were expelled to Libya and 126 to Egypt.[37]

As the then-Italian Minister of the Interior Giuseppe Pisanu commented:

Once again, we are facing an attack conducted by criminal organizations that unremittingly exploits illegal migrants … We will respond, as always, in a firm manner. We will provide the necessary assistance and necessary medical treatment and we will take back to the country of origin those that are not entitled to stay in Italy. The individual measures of repatriations are carried out in respect of national and international rules.[38]

Similarly, in April 2005, the Undersecretary at the Ministry of the Interior, Michele Saponara, claimed that the above-mentioned return flights took place with the consent of Libya and with respect for human rights laws as well as existing international laws.[39]

In October 2004 and March 2006, two Italian parliamentarians happened to be in the reception center at Lampedusa while the migrants were repatriated. One of the two provides an insightful account of their experience:

While we were in the center of Lampedusa, from some documents that we saw we realized that these people were collectively repatriated under the same name. We saw long lists repeating the same name. Hence, we believe that they were not properly identified. Moreover, these people were not given the possibility to apply for asylum … We raised this issue during a parliamentary interrogation, asking the Government how it could send back to Libya people that had not been identified. The response was that those people had been identified. Yet, when we asked if we could have the lists [with the names of those repatriated proving that they had been identified], we were told that for privacy reasons this request could not be met.[40]

The formal position of the Italian Ministry of Interior remains that the people removed to Libya had been individually identified.[41]

On May 12, 2005, over 800 people arrived at Lampedusa[42], and two days later, an Alitalia flight carried 67 people from Lampedusa to Albeida in western Libya.[43] Significantly, on May 10 the Third Section of the European Court of Human Rights requested the Italian Government not to expel 11 immigrants who had appealed to the Court.[44] (The international pressure on Italy to halt the repatriations shall be explored further below).

A fifth series of return flights from Sicily took place between June and July 2005. On June 22, the Italian authorities removed at least 45 people to Libya.[45] Other sources report that on July 13, 64 Egyptians were transferred to Libya.[46]

Other flights from Italy to Libya were arranged in August 2005. On August 10, 2005, 65 migrants were put on an Alitalia flight to Libya.[47] Between August 21-27, 130 Egyptians arrived at Lampedusa and were transported first to Porto Empedocle and then to Catania Airport to be put on two military flights to Libya.[48] On August 31, another 165 Egyptians were taken from Lampedusa to Libya.[49]

Overall, Libyan authorities indicate that in 2005 the number of foreigners removed from Italy to Libya totaled 1,876.[50] A similar figure was confirmed by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture. It documents that, in 2005, 21 flights were organized to remove 1,642 foreign nationals from Lampedusa to Libya and 221 from Crotone.[51] A report it published in 2007 clarifies that in 2006 only one repatriation flight took place.[52] In fact, on March 28, 14 people were removed to Libya.[53]

Different sources document that most of the foreigners removed to Libya were repatriated directly to third countries. A report by the European Parliament (EP) cites Libyan authorities saying “that the hundreds of illegal sub-Saharan migrants sent back to Tripoli by the Italian authorities in 2004 and 2005 have, in most cases, been repatriated to their countries of origin.”[54] Similarly, Human Rights Watch reports:

Different sources document that most of the foreigners removed to Libya were repatriated directly to third countries. A report by the European Parliament (EP) cites Libyan authorities saying “that the hundreds of illegal sub-Saharan migrants sent back to Tripoli by the Italian authorities in 2004 and 2005 have, in most cases, been repatriated to their countries of origin.”[54] Similarly, Human Rights Watch reports:

The quickest returns are of persons sent back from Italy because the Libyan and Italian governments have arranged their onward removal to countries of origin prior to their arrival. “This is arranged before they come [from Italy] so we do not hold them” said Hadi Khamis the director of Libya’s deportation camps. He explained: “They are not held in al-Fellah but sent right home.”[55]

Since March 2006, no further repatriations to Libya have been reported. However, official statements from the Italian Ministry of the Interior are ambiguous on this matter. Interestingly, in May 2006 during a visit to Lampedusa, the Undersecretary of the Interior, Marcella Lucidi, declared that there would “no longer be expulsions of immigrants to those countries that have not signed the Geneva Convention, and among them, Libya.”[56] Yet, shortly after this statement the Undersecretary was reported clarifying that the “expulsions” to Tripoli would “not be indiscriminate.”[57] Nonetheless, there is no evidence that expulsions from Italy to Libya continued after March 2006.

Notably, the return flights described above have been condemned widely. Italy has been criticized by the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture, Amnesty International (AI), the UNHCR, the European Parliament and a group of Italian and Spanish NGOs. Italy has also been asked to justify the expulsions before the European Court for Human Rights and the Italian Ministerial Tribunal. Among the criticisms leveled, the most relevant ones for our purposes concern 1) the absence of a standard readmission agreement between Italy and Libya and 2) the Italian legal basis for conducting return flights. I now consider the responses provided by the Italian government on these matters and the institutional constraints Italy had to face.

Different positions have been taken by Italy as to the existence of the readmission agreements with Libya. An Italian official in Tripoli maintained that there are no readmission agreements between the two countries.[58] By contrast, a senior official at the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that was involved in the negotiations of the Joint Communiqué in 1998 and of the Memorandum of Understanding in 2000 claimed that an Italian-Libyan readmission agreement had been agreed upon. During an interview, when I argued that no formal agreements on this matter have ever been discussed in the Italian Parliament, he responded that verbal agreements hold juridical value.[59]

The statements of the Italian Minister of the Interior show that the two countries agreed informally to undertake repatriations from Italy to Libya and from Libya to other countries. On September 17,, 2004, Pisanu praised the agreements with Libya for succeeding in repatriating such a significant number of foreign nationals[60] and on September 27, 2004 he confirmed that Libya had already accepted the repatriation of 800 immigrants.[61] Moreover, on October 8, 2004 the Italian Minister of Interior reiterated before the Chamber of Deputies that:

The removals to Libya have been carried out on the basis of the agreements with the Libyan Government and they reflect the agreements already finalized with many third countries from the southern shore of the Mediterranean. However, the bilateral agreements between Italy and Libya cover neither the treatment of the foreigners expelled from Italy nor the modality of their expulsion to the country of origin. The agreements […] concern the fight against illegal migration and human smuggling, as well as the provision of [technical] equipment and cooperation aimed at saving lives during the Mediterranean crossing.[62]

The same point was endorsed by other governmental officials. On October 14, 2004, appearing before the Senate, the former Undersecretary of the Interior, Alfredo Mantovano, made it clear that the expulsions to Libya were envisioned in the agreements with Libya.[63] During an interview with a high ranking official at the Italian Ministry of the Interior explained the reasons for their informality.

We had to address the issue of people dying off-shore […] If one of our partners, and I don’t necessarily want to say Libya, for its own reasons, is willing to have an agreement only if its items remain secret for a certain period of time, I much prefer to have this agreement, even if it is informal, instead of nothing at all. This is particularly the case when this could help save human lives and prevent unbalanced situations between countries of origin and of destination.[64]

Likewise, in a letter to Human Rights Watch, Giuseppe Panocchia, the Italian Foreign Ministry’s representative, attested that the removals to Libya “are based on informal agreements developed in the course of diverse bilateral meetings at ministerial level.”[65] Further, before the Ministerial Tribunal, Carlo Mosca stated that flights to Libya and the subsequent repatriations to Egypt took place with the consent of Libya but “in the absence of formal readmission agreements.”[66] This position is consistent with the response of the Italian government to the European Court of Human Rights, which claims that “there is no agreement with Libya on readmission of illegal migrants.”[67]

This leads to the second issue, concerning the admissibility of the return flights from the viewpoint of Italian legislation. The Italian government argued that the repatriations were lawful measures. In the formal response to the appeal before the European Court of Human Rights on the repatriations which occurred from September 29 to October 6, 2004, the Italian government clarified its position with regard to the non-refoulement principle and the nature of the cooperation with Libya. It argued that the return flights to Libya fall under the definition of “respingimento”[68] and is to be confused neither with “refoulement” nor with “expulsion.” “Respingimento” is defined in Articles 10 and 13 of the Unified Text on Immigration as a situation in which “the border police sends back foreigners crossing the borders without the necessary requirements for entry into the State’s territory as provided for in the Unified Text.” Simply put, the Italian government rejected the charge of breaking the non-refoulement principle by arguing that it had applied the principle of “respingimento.”

However, a number of observers have questioned the legality of such measures on human rights grounds. For instance, the UNHCR repeatedly lamented the fact that the Italian government did not take the necessary precautions to ensure that it was not sending back any bona fide refugees to Libya, which was not considered a safe country of asylum at the time.[69] The same organization also expressed deep regret “for the lack of transparency on the part of both the Italian and Libyan authorities.”[70] Likewise, Amnesty International expressed concern “that these people might be returned without an effective opportunity to apply for asylum.[71] On the basis of the information available, the Italian government has never provided a list of the people repatriated from Lampedusa.[72]

In sum, the lack of clarity on the issue of the legality of the return flights from Italy to Libya and their sudden interruption in March 2006, despite the continuation of undocumented arrivals to Italy from Libya, demonstrates Italy’s ambiguous legal stance.[73] Correspondingly, the acceptance by Libyan authorities of the repatriations from Italy invites reflection on their position towards migration.

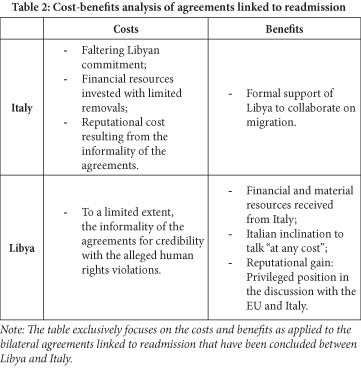

Cost-Benefit Analysis

In order to unpack the give-and-take framework, and assess whether the Italian-Libyan interaction constitutes relations among unequals, I now move on to study the costs incurred and benefits accrued[74] by both countries as part of the wider agreements on migration.[75] By locating the agreements linked to readmission within patterns of diffuse reciprocity, I analyze how participants calculate benefits and costs of acting in accordance with, or against, common norms.[76] The analytical tools provided by Keohane illustrated above help answer one of the initial questions on the patterns of reciprocity between the two countries.

In agreeing to conclude such agreements, Libya reinforced its international standing. Its willingness to collaborate with the Italian government on migration issues was partly responsible for the reintegration of Libya into the international community. After decades of political insularity, such bilateral cooperation allowed Libya to portray itself as being at the forefront in the fight against irregular migration and international terrorism. To rephrase Lipson, complying with Italy’s request provided Libya with a “reputational” gain.[77] The bilateral collaboration with Italy offered Libya “the opportunity to be seen to be cooperating in combating the smuggling of persons” and enhanced Libya’s reputation as a responsible state.[78] Not surprisingly, the onset of the repatriations coincided with the lifting of the European embargo on Libya and the inauguration of a gas pipeline to Italy (see Paolo Cuttitta’s chapter). Arguably, Italy’s critical contribution to normalizing Libya’s relations with the EU was rewarded with the Libyan concession of repatriating migrants who had just arrived in Sicily.

Libya’s formal support for Italian initiatives to combat undocumented migration represents a time-specific benefit with limited resource costs given that the flights were funded by the Italian government. The limited cost derives, also, from a distinctive aspect of the repatriations. The migrants repatriated were not Libyan nationals.[79] Their flights simply transited through Libyan airports and from there they were directed to third countries. In other words, as the flights were sponsored by the Italian government and were not ultimately repatriating Libyan nationals, Libya had virtually no obligations. At the same time, it enjoyed significant rewards, specifically by repairing of its pariah image. In the light of the substantive Libyan interest in full rehabilitation within the international community, the benefits of compliance with the Italian requests on the return flights were higher than those posed by defiance.

More substantially, the centrality of migration in the bilateral discussion has furnished the northern-African country with satisfactory results in its overall interaction with Italy. Italy will talk at “any cost.” This is due, in part, to the internal political and public pressure to address the alleged crisis of Libyan migration.[80] Italy has made significant concessions that, as I argue below, outweigh its benefits from the bilateral collaboration. The increasing relevance of migration reinforced by the pervasive securitized discourse throughout Italy and Europe has reduced to zero the free-riding option for Italy in the cooperation with Libya. Crucially, Libya is aware of this and has successfully emphasized the perceived security benefits of tighter migration policies in order to advance its own agenda.

The main costs to Libya center on the agreements’ informal nature. It is well known that the Libyan regime tends to prefer oral arrangements to written ones. As a representative of an international organization based in Tripoli pointed out:

The written contract does not have any value … Here [in Libya] written agreements … have limited value compared to the value that it has for us [in the Western world] …The contract is actually seen as a way to cheat and not to protect … In this clan-based society honor has a much bigger value than a piece of paper.[81]

The critical point here is that the Libyan tendency towards informality with Italy posed a relative cost for the Jamahiriya. The criticism from the international community relatively lessened the real improvement in its international status that Libya hoped to enjoy from the agreements. Whereas the flights were managed and financed by the Italian government, Libya’s support for these practices was perceived to confirm its poor reputation on human rights. For example, the protests against Qhadafi during his visit to France in December 2007 were grounded on the regime’s general repatriation practices and, more generally, on its continual infringements of human rights.[82] Hence, the regime’s endorsement of the return flights may have had negative consequences for its overall foreign policy agenda. Yet, in broad political terms, it can be argued that the unclear nature of the agreements and the criticism directed to Libya with regard to human rights issues have not significantly affected Libya’s behavior on migration and overall foreign policy interests.

On the one hand, despite the persisting criticism illustrated above, the international community has increasingly sought to strengthen its ties with the Colonel. The meeting between then-US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and the Libyan Foreign Minister in Washington in January 2008 was not conditioned on the improvements in human rights.[83] In short, Libya’s collaboration with Italy on the removal of undocumented migrants has not presented a significant obstacle to the pursuit of its interests.

On the other hand, however, international pressure has not encouraged Libya to change its policies. In fact, the number of migrants removed from Libya to third countries has increased over the recent years.[84] In pursuing and publicizing such actions, the Libyan regime has sought to convince Europe of its commitment to tackling migration and to raise concern over the far-reaching social, economic, and political problems that immigration poses to Libya.

Hence, in employing Keohane’s terminology as defined at the beginning of this chapter, it appears that from the Libyan perspective the agreements linked to readmission and the wider negotiations on migration with Italy have involved limited obligation. Furthermore, they did not expose Libya to the threat of exploitation by Italy. Libyan compliance with the short-lived Italian requests to support repatriations has led to a positive pay-off in which the benefits outweighed the costs.

Let me now turn to Italy’s cost-benefit analysis. One of Italy’s major gains from the agreements is Libyan consent to collaborate on migration. Yet, this collaboration is more formal than de facto. The inability of the Italian government to reduce significantly unwanted migration from Libya and to convince the Libyan regime to fully respond to Italian requests sheds light on resilient constraints. The piecemeal willingness of Libya to uphold the bilateral collaboration on migration makes Italy dependent on its counterpart for the successful implementation of the cooperative arrangements. The non-unitary nature of the Libyan regime, and its multiple identities and interests epitomized by the double agenda illustrated above, impose significant limitations on Italy. Arguably, Libya’s lack of sustained willingness to comply may be linked with Libyan police corruption. The recent report by Frontex (2007) observes that corruption may play an important role in the migratory situation in Libya.

As evident as it may seem, no matter what sophisticated equipment or advanced border management concept and system might be put in place, the existence of corruption will always undermine the implementation of an effective border guard response.[85]

Other commentators have argued that unwanted migration to and through Libya is not only tolerated but actually encouraged by the Libyan regime.[86] By officially supporting the fight against “illegal” migration while, in reality, tolerating smuggling networks, Libya reduces Italy’s potential gains. Libya’s corruption and double agenda impose substantial costs on Italy. The latter has invested significant resources and taken on new responsibilities to control migration from Libya, and yet has failed to obtain its desired outcomes, i.e., to bring under control irregular arrivals to Italy from Libya.

In addition, the informality of the agreements has created a further constraint on Italian action. Indeed, the Italian government was asked to justify the agreements before numerous international organizations. Presumably due to mounting international pressure, in March 2006 Italy interrupted the return flights. The short-term benefits of reducing undocumented migrants were overtaken by the costs of justifying ambiguous and controversial removal policies. Simply put, the reputational cost[87] resulting from the questionable nature of the agreements became too high. This may explain the sudden policy change during the Berlusconi government, which was confirmed by the subsequent Prodi government. However, as I discuss in the conclusion, the implementation of the push-backs from Italy to Libya in 2009 may potentially question this view.

The cost-benefit analyses for Italy and Libya set the framework for answering the question on mutual obligations and assess whether the Italian-Libyan non-standard agreements linked to readmission are based on reciprocity. The arrangements entailed obligations on both sides. The Italian government was expected to finance the flights from Italy to Libya and from Libya to third countries and the Libyan government was expected to allow the transit of such flights. Thus, the Libya’s task was limited compared to the Italian commitment to manage the flights. Within the specific framework of the bilateral agreements, while Libya could free-ride without negatively affecting Italy, the opposite was not the case. As observed, Italian withdrawal would not, and did not, alter Libya’s overall gain-loss balance. Indeed, Libya had limited obligations. Because of the negligible costs involved and the significant benefits, it had virtually no incentive to default. Consequently, the bilateral agreements exemplify a situation of imbalance that is at variance with the basic character of Keohane’s reciprocity norm, under which obligations should be proportionate to the benefits enjoyed by both parties[88]. Hence, since there was little prospect of equivalent exchange the Italian-Libyan non-standard agreements linked to readmission can be defined as relations among unequals, with Italy being in the weaker position.[89]

Nonetheless, the appreciation of the broader agreements on migration may help recast such an imbalance and invite further reflection on the complex and diffuse reciprocity at work.[90] Indeed it has already been suggested that Italy adheres to such an imbalance in the bilateral agreement on migration with the expectation of larger gains in their overall political and economic relationship.[91]

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on the implications of the bilateral agreements between 2004 and 2006 to critically examine the bilateral bargaining dynamics. Given the ongoing and complex nature of the Italian-Libyan agreements my conclusions are neither final nor comprehensive. For example, the recent developments may well challenge the idea that the two countries have failed to bring migration under control. Indeed, since May 2009 Italy has been pushing back boats with irregular migrants arriving from Libya that had been intercepted in either international or national waters. In reversing its long-standing stance, whereby push-backs and joint-patrolling were considered an infringement of its sovereign power, Libya has accepted boats with undocumented foreign nationals who had left from Libya.[92] Furthermore, in concomitance with the implementation of the agreement in August 2008 and, inter alia, the beginning of the construction of the highway as “big gesture” to apologize for the colonial past, the arrivals of irregular migrants from Libya have decreased by 90% compared to 2008.[93] What, then, do the agreements linked to readmission, and concluded between 2004 and 2006, tell us about the broader and evolving collaborative arrangements between the two countries? Does the examination of the readmission agreements hold any relevance beyond the specificity of the selected bilateral case?

My empirical examination of the Italian-Libyan agreements linked to readmission reveals the existence of multiple equilibria which distinguish the dynamics in bilateral bargaining. As far as these agreements are concerned, it has been suggested that their informality have placed much greater political and financial costs on Italy than on Libya. The corollary of this assumption is that the cooperation on the charter flights aimed at removing unauthorized aliens from Italy to Libya constitutes a situation that Keohane defines as unequal reciprocity at the advantage of Libya. In the negotiations on migration, Libya is the most advantaged player who has to be induced to take part in the cooperation, while Italy has little choice but to cooperate with Libya.[94] In other words, the high cost of ensuring Libya’s commitment creates a situation of “vulnerability” for Italy.[95] The patterns of cooperation on readmission reflect relations among unequals where practitioners are, at various degrees, exposed to the danger of exploitation and uncertain arrangements. In other words, the agreements linked to readmission analyzed in this chapter, as well as the overall negotiations on migration, are based on exchanges of “mutually valued but non-comparable goods and services,”[96] whereby the behavior of each party is contingent on the prior steps of the other.

This chapter has not examined the more recent developments concerning the push back operations to Libya. Nor has it dealt with the broader framework of interaction in which the relations between Italy and Libya have developed to date. These elements are analyzed in the chapters written by Paolo Cuttitta and Silja Klepp.

Rather, I sought to reflect upon power dynamics underlying the conclusion and implementation of the Italian-Libyan agreements linked to readmission. In so doing, I provided a tentative analytical framework which could be applied to other bilateral arrangements on migration. From a general point of view, it is possible to speculate that the increasing relevance of migration issues in the international arena may significantly affect the patterns of states’ interdependence while offering an opportunity to rethink substantially the mainstream reading of North-South power relations. Admittedly, my hypothesis, which views migration as a source of soft power, cannot be tested with a single case study. Nonetheless, it invites more systematic research on the complexities and contradictions of evolving North-South relations.[97] It is unlikely that an analysis based on North-South polarization would thoroughly account for the complexities and tensions existing between the conclusion of bilateral agreements and their concrete implementation. The analysis of reciprocity and obligations provides a useful tool for probing beneath multifaceted and changing dynamics in which states cooperate or not. A thorough examination of migration, viewed from an IR perspective, may shed new light on global interdependencies and, more interestingly, on the magnitude of the changes affecting the international system.

[1]. Jean-Pierre Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighborhood,” The International Spectator, Vol. 42 (2007), p. 182.

[2]. Robert L. Rothstein, The Weak in the World of the Strong (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977), p. 9.

[3]. Elspeth Guild, “The Borders of the European Union,” Tidsskriftet Politik, Vol. 7 (2004), p. 34.

[4]. Chris Brown, Understanding International Relations (Basigstoke: Palgrave, 2001).

[5]. Elspeth Guild and Didier Bigo, “Le visa Schengen: expression d’une stratégie de ‘police’ à distance” [“The Schengen Visa: An Expression of a Police Strategy at a Distance”], Cultures et Conflicts, Vol. 49 (2003); Andrew Geddes, “Europe’s Border Relationships and International Migration Relations,” JCMS, Vol. 43 (2005).

[6]. The analysis is based on official documents and semi-structured interviews conducted in Italy and Libya between 2006 and 2008. All the interviews are kept anonymous and the organizations where interviewees are based will not be disclosed.

[7]. Robert O. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” International Organization, Vol. 40 (1986), pp. 1-27.

[8]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 3.

[9]. I elaborated this three-fold categorization based on, but not strictly following, Keohane’s work. Hence, responsibility for this clear-cut differentiation remains with the author.

[10]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 5.

[11]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[12]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[13]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[14]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 21.

[15]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 21.

[16]. Bilateral Agreement on Counterterrorism, Organized Crime, and Illegal Immigration (December 2000).

[17]. House of Representatives, Seat No. 329, June 25, 2003, Hearing by Giuseppe Pisanu, Minister of Interior, http://legxiv.camera.it/organiparlamentari/assemblea/contenitore_dati.a….

[18]. Ministry of Interior, “The Libya-Italy Agreement on Patrol on December 29, 2007,” http://www.interno.it/mininterno/export/sites/default/it/sezioni/sala_s….

[19]. Claudia Gazzini, “Assessing Italy’s Grande Gesto to Libya,” Middle East Report Online (2009), http://www.merip.org/mero/mero031609.html.

[20]. Chamber of Deputies Meeting of July 5, 2007, Response of the Secretary Marcella Lucidi urgent interpellation No. 2-00623, June 26, 2007, http://leg15.camera.it/resoconti/dettaglio_resoconto.asp?idSeduta=0184&…

[21]. Human Rights Watch, “Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees,” Volume 18, No. 5(E) (2006), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2006/libya0906/.

[22]. Ferruccio Pastore, Italian-Libyan Relations and Migration — How to Get Out of This Impasse (Rome: CESPI, 2008).

[23]. Senate, 214th Assembly seat — verbatim May 25, 2009, p. 4, http://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/BGT/424000.pdf

[24]. “L’ira di Gheddafi con Berlusconi: ‘Tratto solo con Pisanu’” [“Gaddafi’s Wrath with Berlusconi ‘Section Only Pisanu”], Il Corriere della Sera, May 27, 2005, http://www.corriere.it/Primo_Piano/Esteri/2005/05_Maggio/26/gheddafi.sh….

[25]. European Commission, Technical Mission to Libya on Illegal Migration 27 Nov 6−Dec 2004 Report, 7753/05 (Brussels: European Commission, 2005), http://www.statewatch.org/news/2005/may/eu-report-libya-ill-imm.pdf.

[26]. Emanuela Paoletti, “Agreements between Italy and Libya on Migration” in A. Phillips and R. Ratcliffe, eds., 1,001 Lights: the Best of British New Middle Eastern Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).

[27]. Senate, 214th Assembly seat - verbatim May 25, 2009.

[28]. Fortress Europe, “Respinti in Libia altri 89 migranti. Erano a 25 miglia da Lampedusa” [“Libya rejected 89 other migrants. They were 25 miles from Lampedusa.”], http://fortresseurope.blogspot.com/2006/01/respinti-in-libia-altri-89-m….

[29]. Ministry of the Interior, “59 Report on Information Policy and Security - 1st semester 2007.”

[30]. Statewatch, Readmission agreements and EC external migration law, No. 17 (2003), http://www.statewatch.org/news/2003/may/12readmission.htm.

[31]. Caritas, Summary — Statistical Dossier on Immigration, XVI Report (Rome: Idos, 2006).

[32]. It is important to bear in mind, however, that this summary of the return flight practices which follows is by no means complete. Further, since it is based on a variety of sources of information, there may be some errors with regard to the numbers of foreign nationals removed to Libya. Hence, the figures I present have to be treated with caution. This sketchy picture may still provide an overall account of the different phases of the practice of organizing return flights. No other public source has documented it in its entirety. To be sure, Human Rights Watch (2006) does list the main repatriations conducted by Libya yet it has some gaps. For example, it does not mention the return flights in March 2006.

[33]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 113.

[34]. Ministry of the Interior, “Immigrants: There Have Been No Mass Return, No One” (2004).

[35]. College for Ministerial Offences, “Report of Obtaining Information - Interrogation of Alessandro Pansa”(2006).

[36]. State Police, “The State Police Repatriates about 200 Illegal Immigrants” (2004), http://www.poliziadistato.it/pds/online/comunicati/index.php?id=622.

[37]. College for Ministerial Offences (2006).

[38]. “Immigration: Pisanu, Firmly Against Yet Another Assault on the Coast,” Ansa, March 13, 2005.

[39]. Senate of the Republic, 776th Public Session, Report Summary and shorthand (2005), http://www.tanadezulueta.it/html/modules/wfsection/article.php?page=1&a….

[40]. Interview by author with Italian parliamentarian, Rome, July 2006.

[41]. Senate of the Republic (2005); Chamber of Deputies, report of the meeting of the Assembly, Seat No. 703 (2005), http://legxiv.camera.it/chiosco.asp?source=&position=Organi%20Parlament…\L’Assemblea\Resoconti%20dell’Assemblea&content=/_dati/leg14/lavori/stenografici/framedinam.asp?sedpag=sed703/s000r.htm.

[42]. “Immigration: Stowaways Try to Flee Even to Lampedusa,” Ansa, May 12, 2005.

[43]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 110; “Immigration: De Zulueta Resumed Deportations from Lampedusa, Berlusconi Government Practice Illegal Expulsions,” Ansa, May 20, 2005.

[44]. European Court of Human Rights, Interim Measures Italy and EU Members States should stop deportations towards Libya (2005), http://www.fidh.org/article.php3?id_article=2419.

[45]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 110.

[46]. “In 2005 More than Four Returns with the Charter,” Il Manifesto, August 11, 2005, http://www.meltingpot.org/articolo5826.html.

[47]. Il Manifesto (2005); “Lampedusa Watching,” Arci (2005), http://www.tesseramento.it/immigrazione/documenti/index.php.

[48]. “Immigration: CRP, Continued Deportations to Libya,” Ansa, August 30, 2005.

[49]. Ansa, August 30, 2005.

[50]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 110.

[51]. European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, Report to the Government of Italy for the visit to Italy by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2005), http://www.cpt.coe.int/documents/ita/2007-26-inf-fra.htm.

[52]. “Immigration: From Lampedusa Repatriated Only 20 Egyptians,” Ansa, March 28, 2006.

[53]. European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (2007), p. 31.

[54]. European Parliament Delegation to Libya (2005), http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/expert/infopress_page/029-3243-339-1….

[55]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 55.

[56]. “Minister of Social Affairs in Lampedusa. Polished, not give back the illegal immigrants who violate the Geneva Convention,” La Repubblica, May 25, 2006, http://www.articolo21.info/notizia.php?id=3633.

[57]. “Il ministro delle Politiche sociali a Lampedusa. Lucidi, Interni: non ridaremo i clandestini a chi viola la convenzione di Ginevra” [Visit of the Minister of Welfare to Lampedusa: Undersecretary Lucidi at the Ministry of the Interior declares: We will not return illegal migrants to countries that violate the Geneva Convention] La Repubblica, May 25, 2006, http://www.articolo21.info/notizia.php?id=3633.

[58]. Interview with an Italian government official in January 2007, Tripoli, Libya.

[59]. Interview with an Italian government official, February 8, 2007, Rome, Italy.

[60]. “Immigration: Pisanu, We are Working on Removing Embargoes Libya,” Ansa, September 17, 2004.

[61]. Ministry of Internal Affairs, “Press Conference by Minister of the Interior Pisanu on Talks with Colonel Qadhafi,” Press Release (2004), http://www.interno.it/salastampa/discorsi/elenchi/articolo.php?idInterv….

[62]. Ministry of Internal Affairs, “Immigrati: Non è stato eseguito alcun respingimento collettivo, nessuno,” October 8, 2004, http://www.interno.it/salastampa/discorsi/elenchi/articolo.php?idInterv….

[63]. Senate of the Republic, 675th Session Public Report, Summary and Shorthand (2004), http://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/BGT/119523.

[64]. Interview by author with Italian government official, Rome, February 2007.

[65]. Human Rights Watch, Stemming the Flow: Abuses Against Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees (2006), p. 106.

[66]. Interrogation to Carlo Mosca before the Ministerial Tribunal. The text was provided by an Italian lawyer.

[67]. European Court of Human Rights, Third Section, Decision on the Admissibility […] (2006), http://docenti.unimc.it/docenti/francesca-de-vittor/diritto-dellimmigra….

[68]. The word respingimento literally means “repulsing.”

[69]. UNHCR, “Italy: UNHCR Deeply Concerned About Lampedusa Deportations of Libyans (2005), http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/423ab71a4.html.

[70]. UNHCR, “Italy: UNHCR Deeply Concerned about Lampedusa Deportations of Libyans,” March 18, 2005, http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/423ab71a4.html.

[71]. Amnesty International, “Immigration Cooperation with Libya: the Human rights Perspective,” AI briefing ahead of the JHA Council, April 14, 2005, http://www.amnesty-eu.org/static/documents/2005/JHA_Libya_april12.pdf.

[72]. Interview with an Italian parliamentarian February 8, 2007, Rome, Italy.

[73]. Chiara Favilli, “What Ways of Concluding International Agreements on Immigration?” Journal of International Law, Vol. 88 (2005).

[74]. The literature on cost-benefit analysis is vast. However, for the purposes of consistency I focus on selected works from the regime literature Krasner (1995).

[75]. Ernst Haas, “Words Can Hurt You; or, Who Said What to Whom About Regimes,” in Stephen Krasner, ed., International Regimes (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995), pp. 23-59.

[76]. Donald Puchala and Raymond Hopkins, “International Regimes: Lessons from Inductive Analysis,” in Stephen Krasner, ed., International Regimes (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995), p. 90.

[77]. Charles Lipson, “Why Are Some International Agreements Informal?” International Organization, Vol. 45 (1991), p. 510.

[78]. Jean-Pierre Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood,” p. 183; Salvatore Colucello and Simon Massey, “Out of Africa: The Human Trade between Libya and Lampedusa,”Trends in Organized Crime, Vol. 10 (2007), p. 83.

[79]. European Commission Report 7753/05, “Technical Mission to Libya on Illegal Migration 27 Nov – 6 Dec 2004 Report,”http://www.statewatch.org/news/2005/may/eu-report-libya-ill-imm.pdf.

[80]. Giuseppe Sciortino and Asher Colombo, Immigrants in Italy (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2004).

[81]. Interview by author with anonymous, Tripoli, January 2007.

[82]. Human Rights Watch, “Human Rights in Libya,” New Statesman, January 14, 2008, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2008/01/14/libya17732.htm.

[83] Human Rights Watch, “Human Rights in Libya,” New Statesman, January 14, 2008, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2008/01/14/libya17732.htm.

[84] Libyan Ministry of Interior, Collaboration on Security between Libya and Italy (2007); Libyan Ministry of Interior, Chart on the Deportation between 2000 and 2005 (2007).

[85] Frontex, “Frontex-Led EU Illegal Immigration Technical Mission to Libya,” May 28−June 5, 2007 (Warsaw: Frontex, 2007), pp. 13-15, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2007/oct/eu-libya-frontex-report.pdf.

[86] Ali Bensaad, “Journey to the Edge of Fear with the Illegal Immigrants of the Sahel, Le Monde Diplomatique (2001), http://www.monde-diplomatique.it/ricerca/ric_view_lemonde.php3?page=/Le….

[87] Lipson, “Why Are Some International Agreements Informal?”

[88]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[89]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[90]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 8.

[91]. Roberto Aliboni, “Mediterranean Security and Co-Operation: Interest and Role of Italy and Libya,” paper presented at the conference on Libya and Italy as a New Model for North-South Relations, Tripoli, Libya, April 14-15, 2002.

[92]. Senate of the Republic, 214ª Seduta Assemblea - Resoconto stenografico 25 maggio 2009, http://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/BGT/424000.pdf.

[93]. Ministry of the Interior, “Illegal Immigration from Libya – Landings decreased by 90%” (2009), http://www.interno.it/mininterno/export/sites/default/it/sezioni/sala_s….

[94]. Alexander Betts, International Cooperation Between North and South to Enhance Refugee Protection in Regions of Origin (Oxford: Refugee Studies Center, 2005), http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/PDFs/RSCworkingpaper25.pdf, p. 45.

[95] Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye, Power and Independence, World Politics in Transition (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 13-15.

[96]. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” p. 6.

[97]. James Rosenau, “The Complexities and Contradictions of Globalization,” Current History, Vol. 96 (1997), pp. 360-364.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.