Originally posted March 2010

The importance of migrant remittances as a source of foreign exchange to labor-exporting countries has increased significantly over time. In fact, quite often, remittances are found to exceed in their flows the more customary sources of foreign exchange, i.e., external borrowing, foreign direct investment (FDI), and foreign aid. Perhaps the main advantage of remittances is related to their appealing characteristic of being costless to the countries of origin, as they would not bear any future financial commitments in relation to them. Given the demographic trends in industrialized countries, it is expected that labor migration will play an increasingly significant role in these economies in offsetting the effects of depopulation on their labor markets. This will be translated into even larger remittance flows to the labor-exporting countries in the future.

Worker remittances to Egypt are a clear example of how important such flows are to the countries of origin. In this case, remittances represent the biggest sources of foreign exchange after exports, and a significant source of household income.

A General Background of Migrant Remittances to Egypt

Egypt is one of the world’s leading labor exporting countries. The mix of Egyptian emigrants includes labor of almost all professions and specializations, emigrants spread all over the world. Within the Middle East Egyptians migrate largely to the oil-producing countries of the Gulf and Libya, and to a lesser degree to Lebanon and Jordan. Outside the Middle East, Egyptians migrate to the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan. Emigration to oil-producing countries is always “temporary,” as residency laws in these countries deny permanent residency to emigrants. Egyptian emigrants who seek permanent residency abroad have no choice but to go to countries where such residency is permissible, in particular to Australia, European countries, and the United States. However, given that labor markets in these countries are highly competitive, only skilled emigrants are able to emigrate to them and receive residency privileges. Essentially, this is a form of the “brain drain” from which Egypt has been suffering. By contrast, most of the Egyptian workers who emigrate to oil-producing countries in the region are less skilled and of lower educational levels, including teachers and clerical and construction workers. All those are temporary migrants, i.e., they have a target level of savings that they seek to achieve and then return to Egypt with those savings.

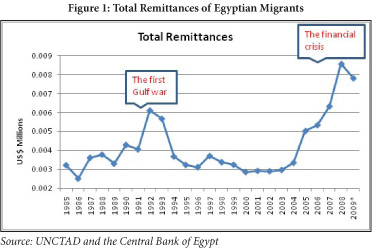

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Egyptian migrant remittances during the period from 1985 to 2000. Emigrant remittances increased from $3.21 billion in 1985 to $8.56 billion in 2008, before falling to $7.8 billion in 2009 as a result of the financial crisis. Although the remittances of Egyptian migrants are flows of private capital, they are substantially affected by a number of economic and political factors. For example, the exceptionally high levels of remittances in 1992 and 1993, which reached $6.1 billion and $5.66 billion, respectively, reflected the developments in the immediate post-Gulf War period, when the Gulf states decided to replace large numbers of Jordanians, Palestinians, Sudanese, and Yemeni workers with Egyptian labor. During the period of 1985-2009, the average annual migrant remittances were about $4.22 billion.

There is no doubt that the evolution of remittances reflects, in addition to economic and political factors, changes in stocks of migrant workers abroad, especially those of temporary emigrants with low skills, who tend to be in high demand in the Arab oil-producing countries in times of expansion. The stock of skilled labor is more stable both in the oil-producing countries and in industrial countries.

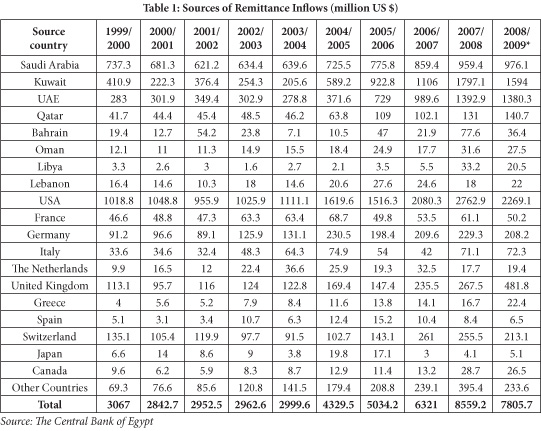

The geographic distribution of the stock of Egyptian migrants abroad is reflected vividly in the sources of remittance flows to Egypt. Table 1 shows the flows of remittances from different immigration countries during the period from 1999 to 2009. It is clear that the United States is the largest source of remittances to Egypt. On average, one-third of all flows of remittances to Egypt are derived from the United States. As mentioned above, migration to the United States is mainly permanent. However, the problem with transfers from permanent migrants is their tendency to diminish, as linkages between emigrants and their country of origin weaken over time. The second generation are primarily associated with their places of birth and have almost no links with their countries of origin. Therefore, unless there is a continuous flow of new emigrants, remittances from permanent migrants eventually stop.

The geographic distribution of the stock of Egyptian migrants abroad is reflected vividly in the sources of remittance flows to Egypt. Table 1 shows the flows of remittances from different immigration countries during the period from 1999 to 2009. It is clear that the United States is the largest source of remittances to Egypt. On average, one-third of all flows of remittances to Egypt are derived from the United States. As mentioned above, migration to the United States is mainly permanent. However, the problem with transfers from permanent migrants is their tendency to diminish, as linkages between emigrants and their country of origin weaken over time. The second generation are primarily associated with their places of birth and have almost no links with their countries of origin. Therefore, unless there is a continuous flow of new emigrants, remittances from permanent migrants eventually stop.

As a source of remittances to Egypt, and with respect to their relative importance, the Gulf states rank second. Egyptian workers transferred $1.5 billion from the Gulf states in 1999/2000. Nearly ten years later, in 2008/2009, remittances have more than doubled to $4.15 billion. Saudi Arabia had been the most important source of remittances for Egypt until 2004, ahead of the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

Since 2004, remittances from Kuwait have grown in an unprecedented manner to the extent that Kuwait has become the most important source of remittances from the Gulf to Egypt. Kuwait has witnessed a huge balance of payments (BOP) surplus and abundant foreign assets due to higher crude oil prices. Soaring oil revenues matched with the adoption of an ambitious plan to transform Kuwait into a financial center resulted in an explosion in construction and infrastructure projects, which in turn drove labor demand in these sectors. This demand has been primarily met from Egypt or from the stock of Egyptians working in the neighboring countries. The substantial rise in the number of Egyptian workers in Kuwait has caused a dramatic increase in remittances to Egypt. In 2007/2008, $1.79 billion were remitted from Kuwait alone, which represented nearly 20% of total remittances flowing to Egypt from abroad, compared to $1.38 billion from the United Arab Emirates and $959.4 million from Saudi Arabia. As such, Kuwait has become the second largest source of remittances to Egypt after the United States.

The Importance of Remittances to the Egyptian Economy

The Importance of Remittances to the Egyptian Economy

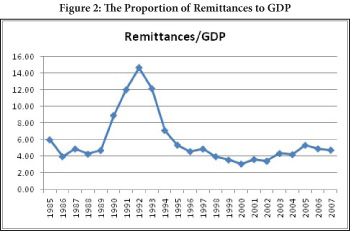

The significance of remittances to the country of origin could be assessed on the basis of several indicators, including the proportion of remittances to GDP. Figure 2 shows the proportion of migrant remittances to Egyptian GDP. As a percentage of GDP, remittances reached a peak during the first Gulf War, with an inflow accounting for about 15%. On average, during the period of 1985-2009, the ratio of remittances to GDP has been about 5.9%. On the other hand, the average remittances per capita peaked in 2008, (at about $105). The average annual remittances per capita during 1985-2009 has been around $61.4. These figures may seem to be low, but if the average number of family members per emigrant is taken into account, in addition to the average per capita income in the country, these numbers become quite significant at the household level.

Until 1994, the remittance flows had exceeded the value of Egyptian exports of goods. Starting from this year (with the exception of 1998), the proportion of remittances to Egyptian exports has continuously declined, reaching its lowest level in 2008, which corresponded to 32.6% of total exports. During the period of 1985-2009, the average ratio of remittances to total exports was at around 105%. In 1991, remittance flows to Egypt amounted to 16 times the FDI inflow. During the period of 1985-2006, the average proportion of remittances to the FDI inflow was about 482%. Remittance flows also were more than five times that of official foreign aid. During the period 1985-2006, the average percentage of remittances to the total official foreign aid was about 210%.

The previous analysis reveals that migrant remittances are vital to the Egyptian economy. Therefore, policymakers must deal with remittances with extreme caution in order to ensure the stability of the foreign exchange market and the Egyptian pound.

The previous analysis reveals that migrant remittances are vital to the Egyptian economy. Therefore, policymakers must deal with remittances with extreme caution in order to ensure the stability of the foreign exchange market and the Egyptian pound.

Policies to Attract Remittances

Unfortunately, when migration of Egyptian labor started to increase at the end of the 1960s and 1970s, Egypt had very strict rules in place regarding holding and dealing in foreign currencies, which led to a flourishing black market for foreign exchange. The black market had been the main venue of remittance flows explained by an undervalued pound. A very active network of black market agents collected currencies from Egyptians working abroad to be used, through informal channels, to finance the smuggling of foreign goods and other illicit trade activities.

To control the black market, the government attempted to reform gradually and partially its foreign exchange policy. In 1971, for example, individuals were granted the right to open special foreign exchange accounts in Egyptian banks. In 1973, a parallel market for foreign exchange was established with the intention of attracting the savings of emigrant workers by offering them incentive exchange rates. In 1974, emigrant workers were allowed to finance imports from abroad. In 1976, individuals were granted the right to hold foreign exchange and to deal in it through licensed banks. In 1977, privileges granted to foreign investors were extended to Egyptian investors to encourage emigrant workers to invest their savings in Egypt. Believing in the importance of migration to the Egyptian economy, the Ministry of Emigration and Working Abroad was established in 1981, which later merged with the Ministry of Labor to form the Ministry of Manpower and Emigration. During the period from 1983-1985, several foreign exchange premiums were granted to emigrants who converted their savings from abroad. Finally, in 1991 the government abolished the two-tier foreign exchange rate system and replaced it with the unified exchange rate. This resulted in the full liberalization of the Egyptian pound, thus avoiding any possible negative effects of the foreign exchange policy on the inflow of remittances.

Determinants of Egyptian Migrants’ Remittances

Despite the importance of remittances for the Egyptian economy, applied research on the determinants of remittances remains very limited. In a panel study of remittances to the Arab labor exporting countries, it was found that remittances are positively related to economic growth in the host countries as well as to inflation in the home country.[1] It also was found that exchange rate differentials between official and black markets have a negative impact on the inflow of remittances through official channels. El-Sakka and McNabb[2] estimated a macro model for the total inflow of remittances through official channels in Egypt. They found that levels of income in both host and home countries have a positive impact on the inflows of remittance to Egypt. They also found that remittance flows are highly responsive to black market premiums. The results also support the hypothesis that interest differentials at home and abroad have a negative impact on the inflows of remittances through official channels. The limited evidence available on the determinants of remittances to Egypt stresses the need for further research to identify appropriate policies aimed at securing increased inflows of remittances through official channels.

References

El-Sakka, M.I.T. (2007) “Migrant Workers’ Remittances and Macroeconomic Policy in Jordan,” The Arab Journal of Administrative Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 307-328.

____________ (2005) “Migrant Remittances in the Middle East: An Overview,” chapter 13 in Terry, D. and Wilson, S (eds.) “Beyond Small Change: Making Migrant Remittances Count” Inter-American Development Bank, Washington.

____________ (1996) “Migration Remittances: Policy Options for Host and Countries of Origin” Final report of research project No. CC023, Research Administration, Kuwait University.

____________ (1987) “Migrant remittances and the balance of payments: the Egyptian case.” Population Studies, Vol. 13, No. 74, Jan-Mar pp. 87-103.

Ghosh B. (2006) “Migrant Remittances and Development: Myths, Rhetoric and Realities,” International Organization for Migration, Switzerland.

Serageldin, et al. (1981) “Manpower and International Labor Migration in the Middle East and North Africa.” Final report, World Bank.

Swamy, G. (1981) “International Migrant Worker Remittances: Issues and Prospects,” World Bank Staff Working Paper, No. 481.

[1]. M.I.T. El-Sakka, “Determinants of Arab Migrant Remittances,” Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 3 (1998), pp. 67-96.

[2]. M.I.T. El-Sakka and R. McNabb, “The Macroeconomic Determinants of Emigrant Remittances,” World Development, Vol. 27, No. 8 (1999), pp. 14

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.