June was a busy month for economic exchanges between Singapore and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In early June, Group-IB, a Singapore-based cybersecurity firm that works with Interpol and Europol, opened its Middle East and Africa Threat Intelligence and Research Center in Dubai. It aims to increase the resilience of companies in the region to higher levels of cybercrime that have accompanied the rapid increase in the value and volume of online transactions. Later that month, Global Foundries, the world’s fourth largest semiconductor manufacturer owned by Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company, announced a $4 billion investment to expand capacity by one-third at its Singapore plant, which it acquired in 2010. This response to the worldwide chip shortage represents Global Foundries’ first new-build foundry in several years rather than a takeover of existing infrastructure.

These two investments are particularly noteworthy because they buck the longstanding pattern of hydrocarbon-led trade and investments. Before considering if they are a harbinger of things to come, a brief review of the current state of economic ties is in order.

Hydrocarbons

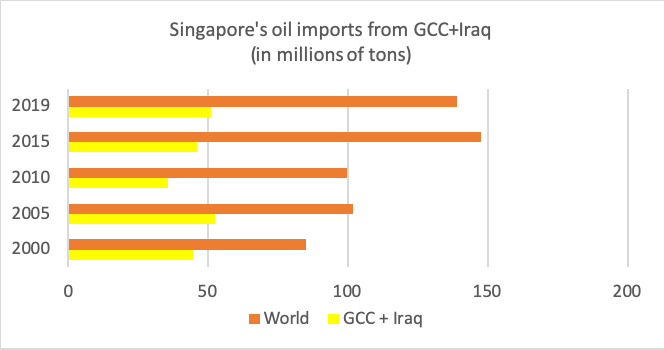

The countries of the Arabian Gulf — the six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Iraq — supply around one-third of Singapore’s oil imports (Figure 1). Most of the oil is either blended/re-exported to the rest of Asia or sold as marine fuel, as befits Singapore’s status as the world’s largest bunkering port and a major oil trading hub. Reliable and cost-effective supply of Gulf oil is hence intrinsic to Singapore’s prosperity.

Figure 1: Singapore’s oil imports (crude and products) from the Gulf region excluding Iran

Source: www.resourcetrade.earth, Chatham House.

Although the region’s share of Singapore’s oil imports has fallen from almost 50% in 2000 to 30% in 2019, this is not a reflection of insecurity in the Gulf. Rather, it is due to the emergence of new and relatively cost-effective suppliers from the U.S. and West Africa happy to backfill declining Saudi supply to the city-state. Crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia have fallen significantly over the past two decades because the kingdom has privileged exports to China, the largest importer of crude oil in the world. At the same time, Singapore’s imports of oil from the UAE have increased, with the latter replacing Saudi Arabia as Singapore’s top oil supplier since 2011.

Qatar, and to a lesser extent Oman, are playing a growing role in Singapore’s domestic energy security, where gas is the fuel of choice for power generation. They are the only two Gulf states that are net gas exporters; Qatar also has the advantage of being the lowest cost producer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the world. By comparison, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are focused on achieving domestic gas self-sufficiency for power and industrial requirements. Gulf LNG exporters are likely to benefit from the imminent expiry of some of Singapore’s piped gas contracts with Indonesia and Malaysia, which will result in LNG accounting for half of Singapore’s gas imports by 2025, up from just under 30% today. A case in point is Pavilion Energy’s deal with Qatar Petroleum to deliver up to 1.8 million tons of LNG per year to Singapore between 2022 and 2032.

Trade and investment

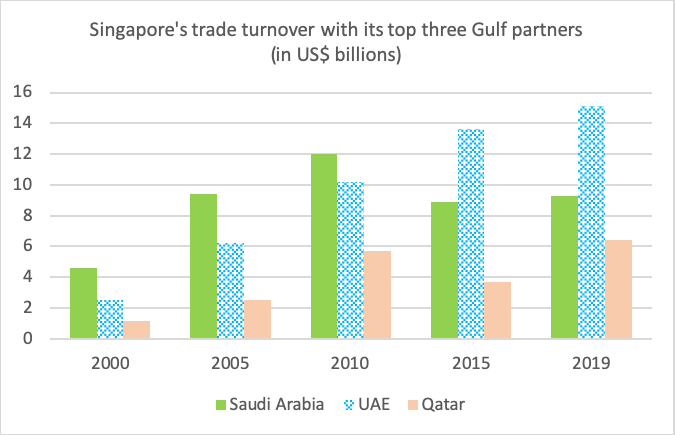

The UAE and Saudi Arabia are Singapore’s largest trading partners in the Gulf, accounting for 2.1% and 1.2% respectively of its total trade turnover in 2019 (Table 2). Singapore’s robust trade with the UAE is testament to the greater degree of non-oil diversification in the UAE, to the latter’s keenness to engage relative to other Gulf states, and to interest in using each other as benchmarks for development and innovation. Joint high-level committees between Singapore and Oman (beginning in 2004), Qatar (2006), and the UAE (2014) meet annually to provide the respective foreign ministries with more direct and systematic oversight over bilateral relations instead of leaving them to the private sector or to ad-hoc contact between ministries. Similar committees have been mooted with Saudi Arabia and Kuwait but they have not been inaugurated.

Figure 2: Singapore’s trade turnover with its top three Gulf partners

Source: Direction of Trade Statistics, International Monetary Fund.

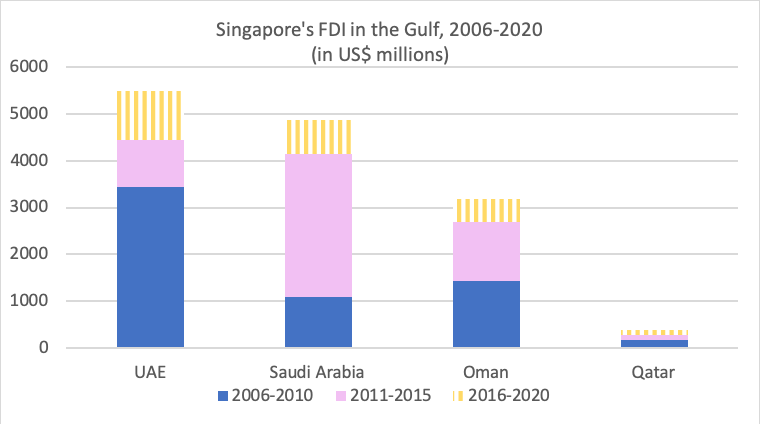

Singapore companies like Rotary Engineering and Trescorp have undertaken engineering, procurement, and contracting work to build oil storage tanks in Fujairah and Jebel Ali (in the UAE), in Jubail (Saudi Arabia), and in Duqm (Oman). The city-state’s leading companies have also invested in the Gulf (Figure 3); they include Keppel’s joint venture N-KOM shipyard in Qatar, SembCorp’s investment in Oman’s Wilayat Mirbat Independent Water and Electricity Plant, SATS’ joint cargo venture with Oman Air, and CapitaLand’s serviced apartments in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

As for the Gulf states, their investments in Singapore include oil storage terminals (by Dubai’s ENOC), manufacturing of resins for plastics (by Saudi Arabia’s SABIC), and real estate (for example, Qatar Investment Authority’s purchase of Asia Square Tower in Marina Bay for $2.5 billion).

Figure 3: Singapore’s FDI in selected Gulf countries

Source: fDi Intelligence, Financial Times.

New trends

The June investment decisions by IB-Group and Global Foundries are therefore distinct from previous patterns of Singapore-Gulf economic interactions. In this regard, they reinforce a growing trend away from hydrocarbons that emerged in the 2010s.

For example, Crimson Logic, a Singapore government-linked company, has worked with all of the Arab Gulf states, with the exception of Iraq, to automate and integrate customs administration systems as well as design and implement e-government platforms to serve judicial, identity, and employment functions during the 2010s. In May 2021, Abu Dhabi Ship Building was awarded a $1 billion contract to build four patrol vessels for the UAE navy, with ST Marine of Singapore providing ship design services; ST Marine previously built naval vessels for the Omani navy between 2014 and 2016. Enterprise Singapore and Abu Dhabi Investment Office are also collaborating to apply innovative solutions to developing a smart city in Abu Dhabi.

As for the Gulf states, data from fDi Intelligence indicate that the UAE and Qatar have been most active with regard to increasing services-based investments — including banking, insurance, travel, and retail — in Singapore over the last decade. For instance, First Abu Dhabi Bank and Qatar Reinsurance Company operate branches in Singapore; in December 2020, Dubai-based Gulf Marketing Group acquired leading sports retailer Royal Sporting House.

The growth in trade and investment in the services sector is likely to continue, especially for Gulf states that diversify away from hydrocarbons. This does not imply, however, that energy will fade in significance in Singapore-Gulf relations. Singapore’s sustainability as a premier oil hub and its ambition to be a regional LNG hub depend on supplies of hydrocarbons from the Gulf.

Additionally, the city-state’s target of halving 2030 peak greenhouse emissions by 2050 is likely to require imports of green hydrogen (or hydrogen formed by renewable energy sources) to decarbonize power grids and maritime transportation. This is because space and weather constraints limit the large-scale uptake of solar and wind energy; Singapore also lacks geological formations to store carbon captured from its refineries and industries. In this regard, a recent study identified Oman’s enormous 25-GW project as among the top five green hydrogen projects in the early or demonstration phases that would be the best fit for Singapore by 2050. According to its consortium of international backers, Oman’s plant will be five times the size of Saudi Arabia’s previously announced green hydrogen project. No other Gulf states made it to the list; Saudi Arabia and the UAE are more focused, at least for now, on scaling up production of blue hydrogen (hydrogen derived from natural gas, after which the resulting carbon dioxide is captured and stored). In any case, the hydrogen trade and related investments are likely to open up a promising new dimension in Singapore-Gulf economic engagement.

Dr. Li-Chen Sim is an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University in the UAE and a Non-resident Scholar with MEI's Program on Economics and Energy. She holds a PhD in Politics from Oxford and is a specialist in the political economy of Gulf and Russian energy and its intersection with domestic politics as well as international relations. Her interests include the politics of energy in the Gulf, Gulf-Asia exchanges, and Russia-Gulf interactions. Her latest book is Low Carbon Energy in MENA (Palgrave, 2021). The opinions expressed in this piece are her own.

Lauryn Ishak/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.