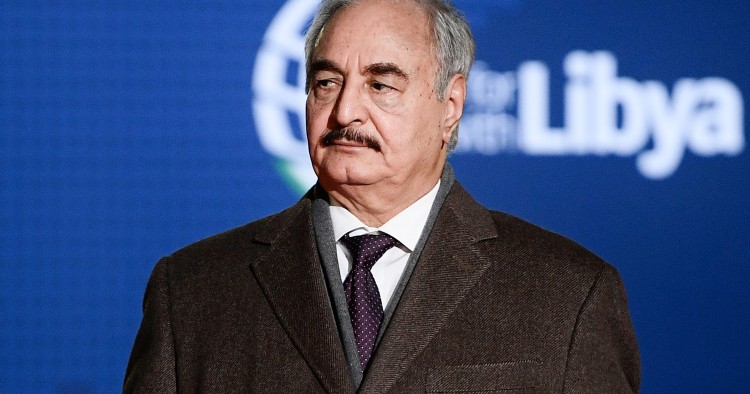

Khalifa Hifter has managed to garner outside support by appealing to foreign states’ desire for a stable Libya, but this rogue former general and would-be authoritarian has proven a troublesome proxy. In supporting his ongoing offensive on Tripoli, foreign states are undermining their own narrative of authoritarian stability.

On April 4th, Hifter launched an all-out assault on Libya’s capital, Tripoli, upending a UN-backed political process two years in the making. Hifter has long been styled by his domestic and foreign backers as a stabilizing antidote to Libya’s chaos. However, a closer look at his actions to date and the dynamics at play as his war effort falters reveals a very different reality. Hifter may have shattered the status quo, but he has not been able to deliver on security and has in fact inflamed the crises he sought to resolve.

More than proxy war in Tripolitania

Since 2014, Hifter’s self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) has benefitted from varying degrees of support from outside backers, including Egypt, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, France, and Russia, either in the form of weapons, military equipment, combat advisors, or funding. Since the beginning of his offensive in early April, Hifter’s forces have been supported by air strikes carried out by Chinese Wing-Loong drones known to have been sold to the UAE. His forces’ initial breakthroughs on the outskirts of Tripoli were, in large part, due to the LNA’s element of surprise, its advanced military equipment, and the tactical advantage afforded by its superior airpower. At a disadvantage, the Government of National Accord (GNA) turned to Turkey for military assistance, which supplied it with Turkish-made Bayraktar armed drones, armored vehicles, and weapons. In doing so, Ankara seemed to be daring the international community to call out violations of the arms embargo on both sides, which no one has been willing to do.

Turkey’s military support proved instrumental in turning the tide. GNA forces utilized the drones as part of a diversion in late June that allowed them to capture Hifter’s main forward base in Gharyan, 60 km south of Tripoli. The discovery there of UAE-made surveillance drones and American Javelin anti-tank systems abandoned by French operatives laid bare the duplicity of Hifter’s foreign backers, who have publicly positioned themselves as peace brokers while providing him with clandestine military support. With the loss of one of his two main supply lines, Hifter’s offensive seemed unsustainable. What followed, however, was an unprecedented escalation of air strikes — beyond the LNA’s domestic capabilities — on areas around Tripoli, Misrata, and Gharyan. Intent on hiding his military shortcomings, Hifter’s foreign backers are increasingly compensating for his weakness themselves.

At the same time, it is misleading to label the Libyan conflict a proxy war as that presumes foreign powers are playing only a supporting role. Direct engagement on the ground has declined, and Hifter’s foreign allies are now seeking to overwhelm the GNA forces with air superiority. While some of the LNA’s airstrikes have destroyed Turkish-supplied drones, the greater concern for GNA-aligned forces is that this escalation may limit their ability to deploy their own drones and airplanes.

However, relying on foreign powers to provide air superiority isn’t a sustainable strategy, nor will it translate into a clean military victory. The latter is far-fetched due to the frailty of Hifter’s military coalition, which could unravel before he even reaches Tripoli. Indeed, internal dynamics between Hifter and his allies reveal a deep sense of mistrust: two prominent allied commanders from Warshefana — in Tripoli’s hinterland — were assassinated in mysterious circumstances in the past month. Currently, Hifter’s only remaining allies with a foothold in western Libya are the Kani brothers from Tarhuna. The latter not only have an independent chain of command apart from Hifter, but also have more authority over his own troops than he does, particularly since the LNA lost Gharyan and moved its main operation room to Tarhuna, placing it de-facto under the Kani brothers’ control. No amount of foreign air support can compensate for the weakness of Hifter’s alliances of convenience. Thus, efforts by Hifter’s allies to make up for his military shortcomings are ultimately self-defeating and may set up western Libya for instability by design.

Disillusionment in Fezzan

Over the years the GNA has been lambasted for ignoring Libya’s southern region of Fezzan — and rightly so. The grievances and sense of marginalization in the region gave Hifter the perfect rationale to expand there in February 2019, supplanting the GNA’s failures with his own successes. In retrospect, however, his internationally-backed operation in the south was merely a springboard for his broader designs. It enabled him to tout his control over the southern region and present his Tripoli offensive as an inevitability, while militarily it gave him the advantage of mobilizing toward the capital from the east and the south. In practice, Hifter integrated some factions into the LNA’s structure, co-opted certain individuals to join his attack on Tripoli, and garnered a degree of social legitimacy by delivering food, medicine, and Russian-printed banknotes.

However, the Fezzan operation also fueled ethnic antagonism between Arabs and Tubu — an ethnic minority group populating Libya’s south — because of Hifter’s deliberate recklessness. Under the banner of fighting “Chadian gangs,” the LNA, along with the predominantly Arab tribes it had mobilized for the operation — such as Awlad Sulayman and the Zway — systematically abused the Tubu, most notably in Murzuq, and displaced them. By mid-March, LNA forces had all but left Fezzan to focus on the Tripoli offensive. A small number of LNA units remained to dissuade anyone from mobilizing to join the GNA in the subsequent Tripoli campaign. More significantly, however, Hifter also left behind a trail of grievances and an even more distorted social peace than was the case before the operation.

Hifter’s expansion into the Fezzan region could have had positive effects had he focused on consolidating his control there. Instead, the withdrawal of his forces and the subsequent vacuum led to a flare up in tensions between the Tubu and Arab communities in Murzuq. Unable to control the situation and lacking additional manpower as a result of the Tripoli offensive, Hifter once again leaned on his foreign backers — although not always with the intended results. For instance, a drone strike on a Tubu gathering in early August killed more than 40 civilians and became a major flashpoint between local Tubu and Arab groups. Over half of the town’s population was displaced in the ensuing intercommunal violence.

Although the displaced civilians are now in the process of returning home thanks to shuttle diplomacy between local dignitaries, the prospects that Hifter’s LNA will once again be able to provide security in Fezzan using the same modus operandi are bleak. Moreover, the ripple effects of the campaign to take Tripoli may galvanize factions in the south to align with the broader coalitions. Though this has not happened so far, it would likely lead to intercommunal violence spreading to other cities in Fezzan.

Buyer’s remorse in Cyrenaica

Hifter’s three-year-long “Dignity Operation” in Benghazi was carried out by a fractious coalition of interest groups, support forces (essentially, neighborhood youth from Benghazi), and tribes from eastern Libya, including the prominent Awaqir tribe. In return, these groups expected him to deliver certain rewards that never materialized. At present, Hifter’s ability to maintain a delicate balance between managing these interest groups’ demands and repressing dissent is slowly dwindling. This partly explains why the main groups mobilized for the Tripoli offensive are from outside Benghazi, notably from Ajdabiya, Tarhuna, and Bani Walid.

In addition to controlling the economy and the security sector, Hifter has presented himself to eastern audiences as an indispensable arbiter who can mediate disputes and transcend tribal and ideological divides. Though easterners may increasingly despise him, they are also worried about the chaos that could ensue in his wake were he to go. Yet tribal and local forces who fought and died for Hifter are increasingly challenging his legitimacy. In Benghazi, this has manifested as friction between different power centers within the LNA.

The LNA’s support forces — largely made up of members of the influential Awaqir tribe — that control downtown Benghazi along with the LNA’s Special Forces, have had several altercations with the LNA’s 106th Brigade, headed by Hifter’s son, Khaled. Tensions have risen over the LNA’s perceived nepotism as well as disputes over territorial control and authority, and Khaled’s unit has now moved its main base to Garyounis, in Benghazi’s southwestern suburbs. These tensions may also explain Hifter’s recent restructuring of the LNA’s security apparatus and the promotion, among others, of Faraj Egaim — of the Awaqir — to a prominent position. While co-option may work in the short term, Hifter cannot co-opt everyone that voices discontent, especially as the conflict drags on.

The protracted war in Tripoli is also exacerbating rivalries between other power centers within the LNA’s apparatus, such as Salafists and Gadhafi loyalists, fueling instability. The violent kidnapping — and perhaps even killing — of Seham Sergewa, a female parliamentarian who voiced her opposition to the war in general and Hifter’s campaign in particular, reflects a worsening security situation in eastern Libya and suggests Hifter will have to resort to greater repression as the conflict continues.

Escaping the zero-sum game

While Hifter’s foreign allies may think they have no choice but to provide military and political support to their protégé, backing his offensive is tantamount to fueling instability across Libya, undermining the very rationale upon which their support is based.

Foreign powers should prioritize stopping the war, instead of getting caught in the zero-sum game of either saving Hifter or exposing the LNA to a dangerous power struggle or fragmentation. Rather than appeasing, funding, and arming Hifter, foreign states should disavow the narrative of security and stability he peddles. Taking a sober look at the mounting disarray left in his wake in areas he’s purportedly stabilized would be an excellent first step in that regard.

Emadeddin Badi is a non-resident scholar at MEI. He is a researcher and political analyst who focuses on governance, conflict, and the political economy of Libya and the Sahel. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Photo by Filippo MONTEFORTE / AFP

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.