At the heart of Malaysia’s capital, Kuala Lumpur, stands the Putra World Trade Center complex, which hosts major events and serves as the headquarters of the United Malay National Organization (UMNO), the leading party in the political coalition that has ruled Malaysia since independence in 1957, the Barisan National (BN).

Adorning the complex are rows of BN, Malaysian, and UMNO flags and large pictures of Malaysia’s six prime ministers, all of whom were presidents of UMNO. At night the complex’s 41-story office tower, which overlooks two congested highways, is illuminated with messages promoting the many achievements of BN and Malaysia.

In the Arab World and beyond, the Putra World Trade Center and the city’s iconic Petronas Towers have cemented a vision of Malaysia in the Middle East as one of the few Muslim nations which has found a viable formula for synthesizing Islam and modernity.

Despite this impressive edifice at home and abroad, domestic support for BN has steadily eroded over the last decade, a process illustrated by the results of the 13th general elections held on May 5, 2013 — the nation’s “judgment day” in the words of Dr. Muhammad Asri (Maza), one of the country’s leading intellectuals and a former state Mufti, who has a vast following on social media. Although UMNO and BN retained majority control of the national legislature and 10 of the country’s 13 state governments, the opposition alliance, the Pakatan Rakayat (the People’s Alliance, or PR) earned 386,285 more votes than BN. Chinese Malaysians, who represent nearly a quarter of Malaysia’s electorate, overwhelmingly supported the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and other PR parties over BN and its traditional Chinese constituent party, the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA). In addition, urban voters backed PR. Ultimately, the election’s results are certain to alter Malaysia’s politics and may impact events in the Middle East, where the Southeast Asian nation is a model for nations undergoing difficult transitions to democratic societies capable of meeting the material and political needs of diverse populations.

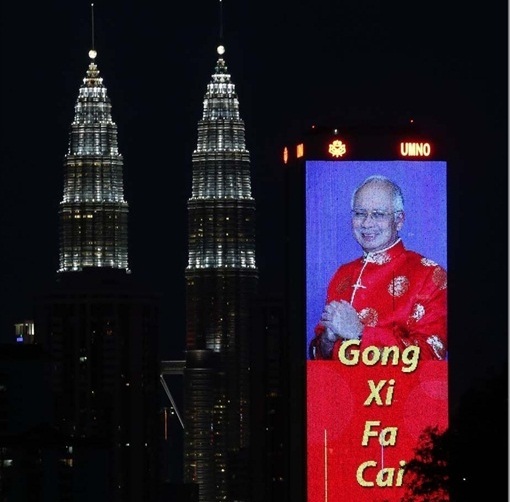

Significantly, Malaysia’s election followed years of attempts by the BN government to win the support of Chinese Malaysians, urban, and younger populations. There have been generous public assistance, a promise of political transformation, and the unveiling of the “Satu Malaysia” (“one Malaysia”) concept, which stressed a vision of Malaysian national identity that transcended race and culture. In addition, the prime minister reformed the nation’s Cold War-era national security laws, long an issue for Chinese and other PR voters. BN strategists specifically targeted Chinese voters with television commercials and posters featuring Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak wearing traditional Chinese clothing. A radio commercial released during Chinese New Year in February 2013 highlighted the fact that the Prime Minister and his youngest son, who had studied at China’s prestigious Beijing Foreign Studies University, spoke Mandarin. The ruling coalition backed a concert that month of the Korean singer PSY in the Malaysian state of Penang, a center of Chinese culture in Southeast Asia. The concert was also meant to appeal to urban voters and the young, who were part of the worldwide craze for PSY’s 2012 YouTube video “Gangnam Style.”

These measures, however, were not enough to win back Chinese voters or assuage their anger for alleged corruption, crime in urban areas, and socio-economic policies meant to promote the welfare of Malaysians who lived in extreme poverty and had not repeated the benefits of modernity: Malays and various indigenous or tribal communities (together known as the Bumiputra). These measures had been put in place to address the factors that led to the 13th May 1969 incident — a series of violent clashes between Chinese Malaysians and Malays following contested national elections. Chinese Malaysian support for the PR was critical to its ability to gain seven more seats at the national level; to retain control of the wealthiest states, Penang and Selangor; and beat four ministers, three deputy ministers and chief ministers. In fact, the DAP was the only party in the PR to gain (national parliamentary) seats in election (10), building on its past success in the state election in Sarawak in 2011 using social media and organization techniques popularized by protesters during the Arab Spring.

Similarly, urban and younger voters, including those who have benefited from post 1969 social and economic policies, lent their support to PR. Many felt that they no longer needed these policies and they shared the concerns of the Chinese and other communities about corruption and the feeling that vast economic monopolies were gouging them. This point was made clear by a popular and humorous YouTube video where a panda representing an average Malaysian goes about his day with signs showing how much he must pay to various monopolies from 8:00 AM to bedtime. Not surprisingly, PR won 9 out of 11 seats in Malaysia’s largest city, Kuala Lumpur. But Malay support for the opposition was not limited to urban areas: PR gained 41 new assembly seats at the state level and won 229 out of a possible 505 state assembly seats, including in states with rural and Malay populations.

While PR politicians have made allegations of fraud in the national elections, it should also be remembered that BN’s policies won the support of key segments of the electorate and that the coalition freely took advantage of the constitutional structure of the country’s government and that structure has important points in common with two nations with longstanding democratic credentials: Great Britain and the United States.

During the campaign, BN returned to its roots as a social democratic party and promised assistance to the poor and rural residents, many of whom are Malay or indigenous people, the largest segments of the population. Party leaders could also point to the Prime Minister’s stewardship of foreign policy and the economy, both of which are stable and have weathered the recent global turmoil better than many other nations. Equally importantly, Malaysian parliamentary seats are allocated at the constituency level and are decided by the same first-past-the-post system used in British elections. The number of electors in parliamentary districts is not necessarily equal and the Malaysian Constitution specifically requires that more weight be given to rural districts. Critically, the rural segment of Malaysia’s population — 28% — is higher than in most developed nations or those in the Middle East and a lopsided loss in an urban area can be negated by narrow wins in other areas.

This framework has a tangible impact on the political process. One only need look at Malaysia’s largest state, Selangor, and its representation in the national assembly. The state has 5.4 million people and 22 parliamentary seats in the national legislature, 17 of which were won by the PR in 2013. By contrast, the states of Johor (3.2 million), Sabah (3.1 million), and Sarawak (2.4 million), are generally more rural and have 26, 25, and 31 seats in the national assembly. BN won 68 seats (82% of the total) in these provinces. These seats were half the number BN needed to have a majority in the national legislature and continue to govern. Sabah and Sarawak are also important because BN won by appealing to non-Malays, who are a key part of the populations of both states.

Nor is BN’s path to victory in the 2013 elections (or a system that favors rural voters) inconsistent with recent elections or the political systems in established Western democratic nations. In 2000, Al Gore received the most votes in the US presidential elections but George W. Bush became president. In 2012, the US Democratic Party won a plurality nation-wide of 1.4 million votes in the Congressional Elections and gained eight seats, but the Republican Party retained control of the US House of Representatives — thanks in part to a system in which state legislatures generally determine the borders of House districts. Each state also has two senators regardless of its population: California’s 38 million residents have the same representation in the upper house of the American legislature as Wyoming’s half a million residents. Consequently, some measures that earn the support of as much as 90% of Americans in national opinion polls can be effectively blocked by legislators from rural states.

However Malaysia moves forward after the 2013 elections, former Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad will play a role. His administration presided over the construction of the Putra World Trade Center, the nation’s economic boom in the 1980s and 1990s, and recovery from the 1997 Asian Financial crisis. He appears regularly in the Malaysian media and is a powerful force on social media and in UMNO because of his promotion of Malay rights and because Chinese Malaysians have seen him as the best manager of the nation’s economy. He is also well known in the Middle East and the Muslim world, where his administration solidified Malaysia’s reputation as a society that reconciles modernity and Islam. A decade after he left office as Prime Minister, his biography stands alongside those of other towering figures of the contemporary era in central Riyadh’s bookstores, and he is asked to be a keynote speaker at key events such as the Egypt-Asia Economic Summit in September 2013 in Cairo, Egypt.

Mahathir and his country’s reputation in the Middle East point to the wider global importance of Malaysia’s 13th general election and the potential for the diverse country to serve as a model for nations like Egypt, which have struggled after Arab Spring revolutions with key existential questions: determining the proper place of religion and women in public life, the role of the state in the economy, and national identity. Indeed, it remains unclear what the place of non-Muslims and secular-oriented populations will be in nations governed by parties that are committed to building states and societies defined principally in Islamic terms.

Few men understand the importance of these debates more than Mahathir. In an April 2013 interview with Malaysia’s leading English-language daily newspapers, The New Straits Times, he argued that while PR promoted individualism and promised to end the “inequality” among non-Malay groups, BN promised a collective vision better suited to country’s multiethnic fabric. He linked BN’s vision to the Cantonese word for a benevolent association or clan, “Kongsi.” Mahathir noted that Malaysia’s first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, employed Kongsi to compel Malaysia’s various ethnic groups to give up some of their rights in order to work together, achieve stability, and deliver growth in a then dangerous world. Nonetheless, he recognized that the PR’s vision was gaining ground because the youth had not lived through the difficult years of Malaysia’s early history when Cold War tensions, ethnic disputes, and poverty threatened to throw the nation into turmoil and necessitated communal cooperation. His observation proved accurate on May 5, as many young Malaysians voted for PR in the thirteenth general elections.

How to resolve the clash of these visions and the tensions between ethnic groups, generations, and urban and rural regions exposed by the election remains unclear. Some Malaysians wore black or made their Facebook id picture black after the election, while BN’s leaders expressed frustration at the Chinese community’s rejection of the government. Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak noted “a Chinese Tsunami” for the PR. The Utusan Malaysia, a Malay language daily newspaper allied with the right wing of BN, ran a headline that many saw as provocative — “Apa lagi Cina mahu” (What else do the Chinese want?) — and compelled some Malays to assert their opposition to racism online. A leading cartoonist, Lat, produced a cartoon of Malaysians of all ethnicities sheltering from the rains of racism and intolerance under an umbrella emblazoned with the Malaysian flag. Among the toughest issues that the Prime Minister will need to resolve will be finding effective representation for Chinese Malaysians in his national administration, since the DAP and the MCA have thus far refused to serve in his government. The Prime Minister may also face a challenge to his leadership from within BN and UMNO due to the losses in the elections. In addition, the future of the PR’s national leader, Anwar Ibrahim, is unclear: he promised that the thirteenth general election would be his last if the PR did not win.

Malaysia’s future may ultimately be decided by a new generation of politicians, such as UMNO Youth leader Khairy Jamaluddin (KJ), and Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Izzah binti Anwar. Both studied at elite Western universities, come from prominent families, and are charismatic leaders, who can think on their feet and establish a rapport with even the most hostile audiences. KJ, who was born in Kuwait, had his reputation as a rising star in BN scarred by the events of the administration of his father-in-law, former Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi (2003–2009). Many wondered if he had appeal in UMNO beyond urban and Westernized Malays. But he won his parliamentary seat in Negeri Sembilan — far from the nation’s large cities — with a majority of 18,357 votes, three times the amount he received in the last election in 2008. And he is now considered a candidate to join the cabinet. For her part, Nurul Izzah binti Anwar is the vice president of the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), one of the three parties in the PR, and has bested two formidable opponents for a parliamentary seat representing Kuala Lumpur. In 2008 she soundly defeated a three-term incumbent and one of the foremost women in UMNO; five years later she defeated a sitting Federal Minister.

In summer 2011, KJ and Nurul Izzah provided a potential preview of Malaysia’s future politics when they appeared on a panel at the Malaysian Student Leadership Summit in Kuala Lumpur and engaged in a debate — an event rarely seen in Malaysia. During the exchange, they showed great poise, command of multiple issues, empathy, humor, and willingness to tackle very sensitive subjects. KJ was especially impressive in his answer to a question asked by a Chinese woman about the social and economic policies put in place after the violence in 1969. While Nurul Izzah effectively “won” the debate, it is likely that it was only the first round of a conversation that will take place again on a larger stage in coming years and determine how Malaysians will addresses the challenges and tensions revealed by the 13th general elections in 2013. Many in Malaysia will be watching — as will many in the Middle East and beyond.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.