For several years, Israeli-Saudi collaboration over regional geostrategy to check Iranian influence has been the worst kept secret in the Middle East since the advent of Israel’s robust nuclear arsenal. Still, public coordination has been taboo, and while indirect, and even direct, coordination may be taking place behind closed doors, no official relationships can develop. This, of course, is due to the history between the state of Israel and the Arab world. The latter has been dealing with the disastrous implications of the imposition of the Israeli state, a Jewish majoritarian enterprise by necessity, in Palestine, a land native to hundreds of thousands of Arabs who have become millions of refugees living precariously throughout the region under military occupation or in refugee camps. The question of Palestine is still the long open wound of the Arab world and, until it is healed, it is hard to see how a Saudi-Israel relationship can move in a more overt direction.

The Saudis, in a move supported by the Arab League and the Organization of the Islamic Cooperation, put forward what became known as the Arab Peace Initiative (A.P.I.) in 2002. As a peace settlement framework, the A.P.I. did not reinvent the wheel. In fact, the conditions it outlined merely involved Israel abiding by well-established international laws and resolutions relating to Palestinian territory. What was novel about the A.P.I. was the broad Arab and Muslim consensus behind it. In short, if Israel merely accepted a solution along the contours of international law, it would open the pathway to normalized relations with every Arab and Muslim country. Even those Arab and Muslim states like Iran and Syria, which have been most ardently opposed to any form of normalization with Israel, would ultimately move in this direction if there was a just peace.

However, in the 14 years since the A.P.I., there have been thousands of illegal settlement homes built, three horrific wars on Gaza, two new Saudi kings, an American war in Iraq, and a nuclear deal with Iran. The shuffling of the regional order has resulted in a seeming convergence of Saudi and Israeli interests, with flirtations of an alliance being brought into the open.

Arabs Need Palestinian Cover

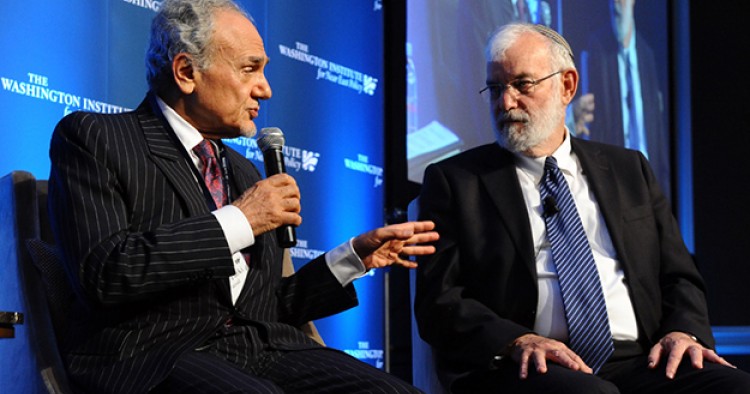

This was on display in Washington in early May when former Saudi ambassador to the United States Turki al-Faisal and retired Israeli Major General Yaakov Amidror held an open meeting hosted by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. The two agreed that there is a linkage between Palestine and the production of a “new Middle East,” a regional realignment that puts Sunni Arab states, Israel and perhaps Turkey on an overtly cooperative axis against Iran. Where they disagreed in this formula is the order of operations. The Israeli interlocutor argued direct collaboration would create the conditions necessary for progress on the Israeli-Palestinian issue, while his Saudi counterpart argued the opposite order.

Interestingly, as the conversation predictably turned to a rehashing of who is to blame for the failed peace process, Robert Satloff, the moderator, asked Faisal “to what extent do the Palestinians need Arab cover … to make whatever deep compromises they will have to make?”

But it is not the Palestinians that need cover from the Arabs to make a deal with Israel, it is the other Arabs that need cover from the Palestinians to enter a “new Middle East” where they openly collaborate with Israel.

The prism of Israel continues to be one through which many in the Arab world understand the region’s politics. In the most recent poll, 85 percent of respondents in the Arab Opinion Index—the largest of its kind in the region—opposed their country recognizing Israel.[1] Sixty-seven percent of the aggregate Arab population said that either the United States or Israel was the biggest threat to Arab security. Only 10 percent of respondents named Iran. Interestingly, when asked about their views about the Iran deal, 40 percent of a predominantly Sunni Arab world supported it while 32 percent opposed (27 percent didn’t know or declined to answer). Despite this, the same respondents believed that Iran (32 percent) would be the main winner of the deal, followed by the United States (31 percent), Israel (15 percent), and then the Arab countries (8 percent). This suggests strongly that Arab publics do not see the geostrategic contest in the Middle East as a zero-sum game between Riyadh and Tehran, even if some regimes might. So, if Sunni Arab states are seeking to create a regional alliance that includes Israel to oppose Iran, doing so overtly will put them in a difficult position with their own citizens at a time of unprecedented economic challenges and notable public discontent.

Israel Won’t Sacrifice the Occupation for Saudi Arabia

If Sunni Arab states think they have a partner in Israel to bring this collaboration forward, as the discussion between Faisal and Amidror might suggest, they would be very much mistaken. An important indicator of this transpired in late May as the Israeli government went through a shuffle.

The Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was initially in talks with opposition leader Isaac Herzog to bring him into the governing coalition.[2] The move would have offered Herzog the foreign ministry and changed the image of the government from right-wing to one more appealing in the eyes of the international community. The idea was that this would open the door to restarting negotiations with the Palestinians, which would, in turn, provide Arab states who are cozying up to Israel the political cover to do so more openly. This requires a leap of faith on the part of the Arabs who, as Faisal made clear, believe actual progress on peace must occur first, before open collaboration.

The talks between Netanyahu and Herzog were supported and pushed by international players including former Quartet envoy Tony Blair and were conducted in apparent coordination with Washington as well. During the later stages of the talks, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi delivered what appeared to be impromptu and conciliatory remarks at an infrastructure conference in Egypt last week. He spoke of achieving a “warmer peace” with Israel if peace with the Palestinians could be reached and that Egypt was ready to play a role to help move this process along. He also called for Israeli leaders to allow his speech to be broadcast to the Israeli public. Netanyahu and Herzog were quick to welcome the remarks on the same day. The Washington Institute’s David Makovsky and also Robert Satloff, who moderated the discussion between Faisal and Amidror, were quick to further the encouraging narrative on Twitter.[3] But just when it seemed like all the pieces were falling into place, there was a dramatic reversal. Netanyahu ditched Herzog and offered ultranationalist hardliner Avigdor Lieberman the post of defense minister in his government, effectively moving the most right-wing government in Israel’s history even further right.

The move caught the Arabs by surprise. “We have to admit that we received a real shock,” an Egyptian official was quoted in an Israeli daily, “We started with Herzog and we're ending up with Lieberman.”

But Netanyahu’s behavior here should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with him. His political career has been one short-term calculated ploy after the other. This shuffle, which is a slap in the face of the Egyptians and an indirect slap to other Arab states, should send a clear signal to the Arab world about flirtation with Israel in the hopes of allying against Iran. Yes, Iran is a concern to Israel, but it will never rise to the level of priority of its internal situation with the Palestinians.

Palestine Trumps Iran for Israel

For Israel, the issue of the Palestinians is as much, if not more, of an existential threat than that posed by the Islamic Republic. Iran, in the eyes of Israel, is a challenge because of its regional alliances and, in particular, its support for Hezbollah, which sits on Israel’s borders and has proven to be an opponent capable of imposing costs on Israel. But these external challenges have proven deterrable. While Hezbollah’s unconventional and asymmetric approach is harder to deter with traditional methods, it is unconventional and asymmetric precisely because of the massive power imbalance between Israel and the rest of the region. Even Iran, a nation-state with a large population, is not in a position to threaten Israel in any conventional way. It lacks the ability to project power across the theater in a prolonged and sustained fashion, and its forces, while larger in number, are poorly equipped in comparison to the Israeli military. And, of course, Israel retains both first-strike and second-strike nuclear capabilities, ensuring that, even if Iran was to take the irrational step of launching a long, drawn out conventional war against Israel, Israel would hold the trump card.

But Israel’s struggle with the Palestinians is of a completely different nature. It is not a challenge that can be deterred with ICBMs or submarines. Between the river and the sea, an area where Israel rules with a mix of both military and civilian law, there are an equal number of Palestinians and Jews. Palestinians live either under military occupation or as second class citizens. Despite this demographic mishmash, Israel claims to maintain both a Jewish and democratic identity. This paradox has been maintained by the pretense of a peace process and the notion that the occupation is temporary and the emergence of a Palestinian state near. As time has marched on, now entering the 50th year since the occupation began in 1967, the Israeli-Palestinian egg is as scrambled as it has ever been, and the prospects of separation are dimmer than ever.

The idea that Israel is interested in peace is oft-repeated and politicized, but under closer inspection of the actual interests involved, one finds that the interests of maintaining perpetual occupation are stacked quite high. Economically, Israel benefits a great deal from the monopolization of the land and resources of the West Bank as well as the captive market and cheap labor force. Billions of dollars have been sunk into settlements over the years. A Haaretz investigation in 2003 concluded $10 billion had been spent on settlements and a new estimate by an Israeli economic think tank puts the number at $30 billion over the previous 40 years, underscoring the extent to which sunk costs have accelerated just in the past 13 years.[4] Additionally, the removal of even a fraction of the settlers needed for a viable Palestinian state would cost the Israeli government approximately 10 percent of its G.D.P. in resettlement costs.[5] During the period of the peace process, as Israel handed over some control of the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority, and European and American players financed them, Israeli defense consumption in relation to its G.D.P. halved.[6] Indeed, Israeli defense consumption in relation to its G.D.P. is at some of its lowest levels historically, which is remarkable considering this is a state running a multi-decade military occupation over a population nearly half its size. The bottom line on the occupation is a profitable one for Israel.

But these are just some of the economic incentives for perpetual occupation. Politically, large scale withdrawal is impossible given the status of Israeli politics today. The right-wing dominates Israeli politics and is primed to continue doing so for years to come. Israeli settlers, who obviously have a direct economic stake in the maintenance of the occupation, as well an ideological opposition to ending it, are playing an increasingly large role as kingmakers in Israeli politics. At the start of the peace process, settlers comprised about 5 percent of the Israeli polity—today they make up nearly 10 percent. That may seem insignificant until one considers that: 1) they are among the most ideologically consistent voting bloc in Israel; 2) they have consistently higher turnout numbers than any other demographic in Israel; and 3) there are a large number of parties in the Israeli system. Because of this, it is hard to imagine a coalition in Israel that is not right-wing today and whose stability is not dependent on this demographic.

Given these economic and political incentives, what reason do Israeli leaders have to shift toward a policy of withdrawal? For Israel, it is far better predisposed to handling any challenge posed by Iran than it is able to deal with the geographic and demographic hole it has dug itself into for the past 70 years. In light of this, it has adopted a policy of using the prospect of peace, via never-ending negotiations, to keep international opprobrium at bay so it will not be forced to confront the difficult internal crisis just below the surface. For these reasons, Israel may flirt with Sunni Arab states from time-to-time to create a veneer of progress, perhaps even under the framework of the Arab Peace Initiative. However, it is not inclined toward taking the actual steps necessary to achieve an agreement under that framework, no matter how much common ground it might share with Sunni Arab states in opposition to Tehran.

Arab regimes who believe otherwise are miscalculating and any doubt about this should be put to rest by Netanyahu’s most recent political maneuvering.

Photo Caption: ©2016 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Reprinted with permission.

[1] “The 2015 Arab Opinion Index: Results in Brief,” Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies, December 21, 2015, http://english.dohainstitute.org/content/cb12264b-1eca-402b-926a-5d068a….

[2] Eran Etzion, “Netanyahu’s Risky Politics and the French Initiative,” Middle East Institute, June 6, 2016, http://www.mei.edu/content/article/netanyahu-s-risky-politics-and-frenc….

[3] David Makovsky, Twitter post, May 17, 2016, 9:39 a.m., https://twitter.com/DavidMakovsky/status/732611608392826880; Robert Satloff, Twitter post, May 17, 2016, 8:16 a.m., https://twitter.com/robsatloff/status/732590503133368320.

[4] “The Cost of Israeli Settlements,” The New York Times, October 3, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/03/opinion/the-cost-of-israeli-settlemen…; Luke Baker, “Israel’s Settlement Drive is Becoming Irreversible, Diplomats Fear,” Reuters, June 1, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-palestinians-settlements-idUSK….

[5] The data in the following link shows that the removal of 5,000 Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005 cost Israel $1.3 billion, roughly 10 percent of its G.D.P. at the time; “Gaza Disengagement Plan: Compensation for Jews Who Lost Homes in Disengagement,” Jewish Virtual Librar, updated July 2011, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Peace/compensation.html

[6] According to the World Bank, defense took up 13.3% of Israel’s G.D.P. in 1993, which has dropped to 5.9% in 2014; “Data: Israel,” The World Bank, accessed June 10, 2016, http://data.worldbank.org/country/israel#cp_wdi.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.