Contents:

- Biden administration makes tactical shifts toward reengaging Middle East in year two

- Great power competition in the Middle East escalates

- From the Ukraine War to OPEC+, the Gulf States increasingly go it alone as free agents

- Russia’s war forces Europe and MENA closer together

- Iran-Russia relations deepen amid growing international pressure

- In Israeli politics, one change led to another

- Iraq ends its year-long political crisis, looks to improving regional relations

- The impact of the rise of a new youth generation

- A year of extreme climate impacts puts pressure on climate policy to deliver

- Egypt exemplifies MENA region’s dramatic human security challenges

1) Biden administration makes tactical shifts toward reengaging Middle East in year two

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

2022 marked an important shift toward deeper involvement in the Middle East by the Biden administration, but it was a re-engagement with limits.

President Joe Biden entered office in 2021 with a modest approach to U.S. policy in the Middle East. Focused on conserving more time and energy for domestic priorities such as the pandemic and economic crisis and other global challenges like China and climate change, the administration sought to avoid the missteps of its predecessors. Common mantras among some members of Biden’s Middle East team were “no more failed states” or going “back to basics,” signaling that the United States would seek to avoid sweeping, ambitious goals for the region. It aimed to re-enter the Iran nuclear deal through diplomacy and redoubled efforts to find a diplomatic solution to the Yemen war.

In the first half of 2022, it was becoming clear that the initial game plan to address the latter two issues was not achieving its stated goals. In addition, a series of attacks by Iran-backed groups against U.S. partners in the region, including Israel and the Gulf states, elevated doubts about America's long-term commitment to the region. Furthermore, Russia’s war against Ukraine and the hedging by some U.S. partners in the region, combined with the growing strains on energy and food prices, prompted the Biden administration to adopt a new and more engaged approach by early summer 2022.

The Biden administration deepened its engagement in key parts of the region as it prepared for the president’s visit to the Middle East in the summer of 2022. The visit led to a number of agreements with key partners such as Saudi Arabia and Israel on a range of fronts, including technology and cybersecurity policy initiatives. It also resulted in innovative agreements, including the I2U2 agreement, which brought together Israel, India, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates and created a framework for promoting joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, and health and food security. Bilateral U.S. Partnerships for Accelerating Clean Energy with Saudi Arabia and the UAE followed in July and November 2022, respectively. Finally, the October 2022 Israel-Lebanon maritime deal was also the product of important U.S.-led diplomacy.

Biden’s November 2022 visit to speak at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh and meet with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi is the most recent example of this new approach. These frameworks present an opportunity for America to shift its focus away from an emphasis on military cooperation and diversify its engagement with the region.

Looking ahead to 2023, the Biden administration faces the continued challenge of how to balance a revived U.S. engagement in the Middle East with other geopolitical priorities such as the Russo-Ukrainian war and China. A second set of challenges will include preparing for additional possible regional turbulence from Iran, Israel’s new government, and unresolved conflicts in Syria and Yemen.

Alongside these challenges are important opportunities to promote de-escalation through diplomacy and greater regional integration that can encourage cooperative efforts to address the pressing economic, social, and political challenges facing people across the region.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

PHOTO: US President Joe Biden arrives at the King Abdulaziz International Airport in the Saudi coastal city of Jeddah, on July 15, 2022. Photo by MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images

2) Great power competition in the Middle East escalates

Ross Harrison

Senior Fellow and Director of Research

Less than a decade ago, a group of major global powers demonstrated the will and capacity to work together for stability and peace in the Middle East. They recognized that regional disturbances were unlikely to stay localized but could quickly become globalized problems in the form of international terrorism, refugee flows, and market disruptions. This seemed to incentivize the United States, Russia, China, and Europe to sidestep their intense rivalries and work cooperatively on several Middle Eastern initiatives. Completing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015, which limited Iran’s nuclear enrichment program, was one profound example, as was the founding of the International Syria Support Group (ISSG). While the latter joint effort, to end the Syrian civil war, ultimately failed, it nonetheless showed that global powers could find sufficient political will to work together toward a more secure Middle East.

By 2022, it became clear that such great power cooperation was a mere fleeting moment and not a trend. Yet the deterioration of these efforts started much earlier. For one, Russia’s entry into the Syrian civil war on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad’s government, in late 2015, pitted it against the United States, which earlier had provided admittedly tepid support to the opponents of the regime. In turn, the Trump administration’s sudden withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 along with its campaign of “maximum pressure” against Tehran created fissures between Washington and its closest European allies as well as incentivized Russia and China to firmly tilt toward Iran and away from U.S. efforts to contain the Islamic Republic.

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine was the coup de grace in terms of the collapse of great power cooperation in the Middle East, firmly pitting the U.S. against Russia in the European and Middle Eastern theaters. At a moment when Russia could have been pushing Tehran to recommit to the JCPOA, it moved dangerously toward a close military alliance with Iran.

While the ramifications of the collapse of the global order in the Middle East will likely play out in 2023 and beyond, what is clear is that 2022 spelled the beginning of a re-intensification of great power rivalry in the Middle East.

We should, however, be cautious about hastily concluding that this will look like a rerun of bygone Cold War competition. Today’s Middle East is a different region than when the United States last competed there with the Soviet Union. Regional countries no longer dance to the tune of superpowers but are more driven by the logic of intraregional dynamics, such as the rivalries between Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel. While great powers still have a significant role to play, the local actors have much more agency and independence of action than ever before.

This empowerment of regional actors we saw in 2022 came about for several reasons. First, Washington’s messy withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine convinced Middle Eastern countries that it was in their interest to hedge their bets rather than cede control to outside powers, whose reputation as responsible and steadfast partners had suffered. We saw this with U.S. allies and partners, such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and even Israel. And we see an emboldened Iran feeling more confident than ever in its relationship with Russia due to Moscow’s dependence on Iranian drones and other military hardware in its fight in Ukraine.

Second, the conflicts in the region today, from Israel-Palestine to the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, reflect local logics, such as problems of poor governance, rather than solely or predominantly the actions of outside powers. Indeed, in many cases, the global powers seem to have given up even the pretense of being able to solve what appear to be chronic conflicts across the Middle East.

That said, outside great powers often retain the option of being a spoiler. The growing partnership between Moscow and Tehran could result in the ultimate failure of an already moribund JCPOA process, bringing to a formal end the edict among global powers of “do no harm” in a region so critical to global security.

As we approach the end of 2022, it is fitting to point to one possible opportunity amid an overall gloomy assessment. Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine may have laid the foundation for rehabilitating the U.S.’s reputation in the Middle East and sharply undermined Moscow’s claims of being the clearer, more stable partner. Depending on how the war in Ukraine plays out, 2022 could prove to be a seminal moment in reestablishing the United States as an undisputed regional broker and partner. To ensure this plays out positively for the U.S. in 2023, Biden administration officials will need to internalize that the Middle East has changed and recognize that regional powers will demand to have a say in how the region unfolds in the future.

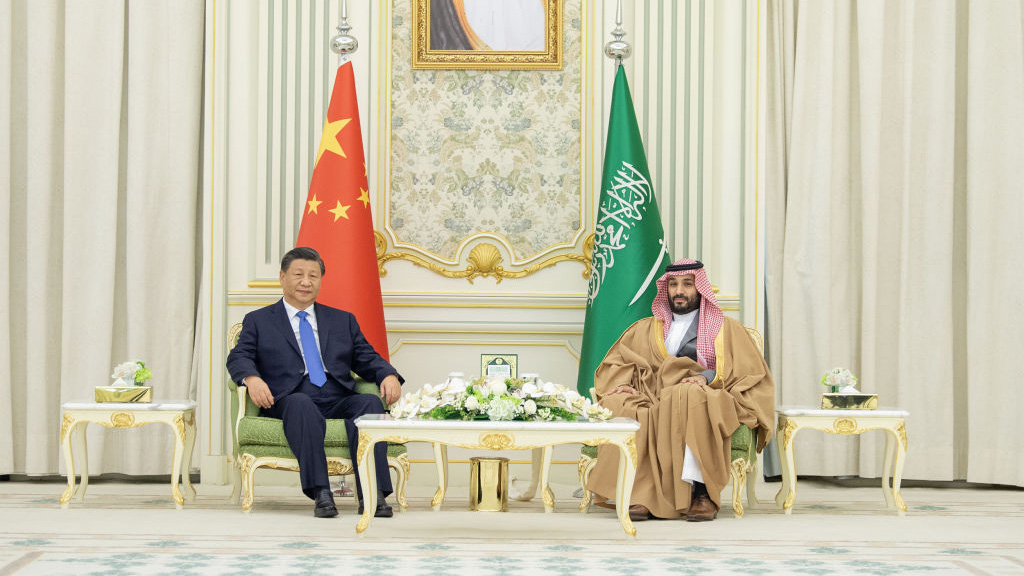

PHOTO: Chinese President, Xi Jinping (L) meets by Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (2nd R) following an official welcoming ceremony at the Palace of Yamamah in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia on December 8, 2022. Photo by Royal Court of Saudi Arabia/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

3) From the Ukraine War to OPEC+, the Gulf States increasingly go it alone as free agents

Gerald M. Feierstein

Distinguished Sr. Fellow on U.S. Diplomacy; Director, Arabian Peninsula Affairs

The Saudi hosting of Chinese President Xi Jinping, on Dec. 8, underscored the dramatic clarification in 2022 of Saudi Arabia’s multipolar foreign policy, very much mirroring the United Arab Emirates’ decisions over the course of the year. Global events, particularly the split in Gulf countries’ reactions over Russia’s aggression in Ukraine as well as the October oil production cut determined by the Saudi-dominated OPEC+ consortium, exacerbated differences with the United States, including on issues ranging from Iran to human rights and civil liberties concerns. Popular perceptions in the U.S. (and in the region as well) have characterized these actions as reflecting hostility, especially toward the Biden administration.

In fact, the Gulf’s differences with the U.S. have been on the rise for many years. Frustrations over U.S. policies — ranging from the 2003 invasion of Iraq to the response to the 2011 Arab Spring popular uprisings and including the 2015 agreement with Iran on its nuclear program — have encouraged closer relations with other great powers, namely China and Russia. Notably, China has emerged as the region’s number one trade and economic partner, while Russia, aided by President Vladimir Putin’s aggressive wooing of Gulf counterparts, has become a key partner in the global energy sector. At the same time, a new generation of leaders in the Gulf, especially Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, and the UAE’s president, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, came to power more determined to pursue an independent foreign policy course that they considered more reflective of their nation’s leadership in regional and global affairs. Included in that determination is a willingness to break with Washington on the response to global issues spanning the gamut, from the Ukraine war to Libya to the Horn of Africa.

As President Joe Biden’s visit to the region in July exemplified, this shift by the leading Gulf states to a multipolar policy does not mean necessarily that U.S. relations with the region have become obsolete. Given the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members’ reliance in the defense and security realm not only on the U.S. defense umbrella but also on U.S. equipment, training, and doctrine for their own militaries, it’s unlikely that the GCC states would willingly move away from a continuation of that relationship. But it does mean that U.S. policymakers can no longer assume that Gulf governments will follow a U.S. lead on setting policy for either regional or global issues. Going forward, to ensure Gulf cooperation, the U.S. side will need to make the case that its policy preferences are consistent with Gulf leaders’ perspectives on their own national interests. Initiatives like the Joint Working Group on Iran should be increasingly a centerpiece of U.S. engagement with the region.

PHOTO: Delegates during a news conference following the 33rd meeting of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC countries in Vienna, Austria, on Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2022. Akos Stiller/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

4) Russia’s war forces Europe and MENA closer together

Iulia-Sabina Joja

Director, Frontier Europe Initiative; Project Director, Afghanistan Watch

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine this year divided the world along similar fault lines as during the Cold War: the West, Moscow and its allies, and the non-aligned countries. The majority of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries chose to avoid making a choice and, thus, de facto fell into the third camp. Whereas most of Europe joined the United States in firmly supporting Ukraine with military, financial, and humanitarian aid as well as punishing Russia with unprecedented sanctions. Even so, the consequences of the war inadvertently ended up bringing the European and MENA regions closer together in various ways.

In the MENA region itself, the effects of the Western-Russian confrontation most immediately made themselves known in the energy sphere. European Union sanctions on Russia and Moscow’s retaliatory weaponization of its energy exports progressively but swiftly decoupled Europe from Russian oil, natural gas, and coal supplies and impelled the West to turn to MENA countries to compensate for the lost resources. Throughout the war, Western leaders visited and hosted their counterparts in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and the United Arab Emirates to secure new hydrocarbon contracts and encourage increased production. Though these developing ties were not able to fully prevent a global energy crisis in 2022, the coming years will likely see a long-lasting European reorientation toward greater reliance on MENA energy supplies even as the EU more forcefully prioritizes a switch to renewables. At the same time, MENA countries will continue to push for greater investments from the West to help expand their hydrocarbon energy sector as well as implement their own energy transitions. This summer’s MENA-Europe Energy Forum, hosted by Jordan, in particular highlighted these trends of growing interdependencies between the two regions.

The 2022 energy crisis was quickly accompanied by a food crisis, caused in large part by the Russian naval blockade of Ukrainian grain exports to the MENA region and beyond as soon as the war began. Ukraine and its neighbors have been scrambling ever since to find or develop alternative transportation routes, managing to facilitate at least some Ukrainian grain reaching the African continent. MENA states like Egypt and the UAE also took the initiative to attempt to secure new agricultural deals with countries on the European continent. Turkey has played an important role in this process of trying to forestall widespread famine in the developing world, notably facilitating a deal to export Ukrainian grain via the Black Sea without Russian interference. Yet Ankara’s position between Moscow and Kyiv has been complicated. Though a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member and a staunch supporter of Ukrainian sovereignty, Turkey never imposed any sanctions on Russia and has continued to benefit from trade with Russia despite the war, increasingly becoming a hub for Russian energy, trade, and tourism at the intersection between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

As the Russian full-scale war against Ukraine approaches the one-year mark, the Black Sea region remains highly unstable and will continue to be so as long as Russia persists in its aggression. Another food crisis, thus, cannot be ruled out next summer, particularly since this past year revealed that while Europe and the MENA region can attempt to manage such calamities, they ultimately can do little to prevent them.

Follow on Twitter: @IuliJo

PHOTO: Demonstrators wave the Ukrainian flag during a rally in support of Ukraine in Tbilisi on February 28, 2022. Photo by VANO SHLAMOV/AFP via Getty Images.

5) Iran-Russia relations deepen amid growing international pressure

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Frontier Europe Initiative

Iranian-Russian relations appear set to enter a new phase. This is a partnership that deserves close attention as the possible implications for Western interests cannot be ignored. From closer military-to-military cooperation to a doubling of annual trade (to around $4 billion) in only a few short years, the momentum is accelerating. Building on military cooperation to keep President Bashar al-Assad’s regime alive in Syria, the partnership has, according to the White House, deepened so much that Iranian specialists are now training Russian forces in the use of Iranian-made drones in the Ukraine war.

At no previous point have the two countries banked on each other as material partners as much as they do today. Nor is this a one-off, and perhaps temporary, coalition. After the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014 — and subsequent Western rebuke — relations between Tehran and Moscow began to deepen, but more in words than in action. Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine was a pivotal turning point, however.

Facing Western sanctions, Moscow sought substitutes for a host of its economic and other needs. As the most and second-most sanctioned countries in the world respectively, Russia and Iran have, at least on paper, a strong basis for collaboration, but implementation is still under way and remains untested.

Iran remains in dire need of investment in critical industries. According to official Iranian statistics, Russia was the “largest” foreign investor in the country’s oil and natural gas industries in the first half of the present Iranian year (March 2022-March 2023). At $2.7 billion, Russia’s investment plans are said to have entered the “implementation” stage. Official Iranian sources have emphasized this fact because Russian companies have a long track record of signing Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) in Iran for economic projects that subsequently fail to materialize. These Russian investments are said to be centered on three “energy and infrastructure” projects, but the funds for them are reportedly already in Iran.

If this is true, it would suggest that, even as sanctions against Russia have been gradually ramped up since February 2022 following its invasion of Ukraine, Moscow has nonetheless been able to find loopholes to bring or transfer funds for strategic projects under development in Iran. As can be imagined, Tehran and Moscow have good reasons to keep the details of their economic cooperation secret to avoid Western detection and reaction. But secrecy around these joint projects has not prevented skeptical Iranian sources from probing into Moscow’s motivations and good faith in dealing with Iran.

An illustrative example is the case of the Rasht-Astara rail link, which is a missing connection for the completion of the International North-South Transport Corridor, set to link Iran to Russia via Azerbaijan. One Iranian source claims that the cost of the project has, in the last two years, increased by three times. It is not clear if this major increase in cost has anything to do with Russia’s participation in the project. The same source reports that the completion of the rail link requires some €800 million, but that it is still not clear if Russia will be able, or willing, to provide the financing for this project.

This skepticism about Russia’s involvement in the final stage of what has been for years hailed as a joint strategic project is very telling on two levels. At best, it demonstrates that Russia is financially unable to invest the relatively small sum of €800 million to complete a landmark and strategically sensitive infrastructure project. At worst, from the point of view of measuring the health of Iran-Russian cooperation, it makes clear that Moscow does not have enough political confidence in Iran as a destination for major Russian investments. But that is certainly not the message that Moscow or Tehran would like to send to the world.

Again, much is already happening in Iranian-Russian relations. The main question for now is whether closer military relations can also help to cement economic ties in the face of the Western sanctions with which both countries wrestle. The West needs to watch this space very closely in 2023.

Follow on Twitter: @AlexVatanka

PHOTO: Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (R) shakes hands with Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian during a joint press conference following their talks in Moscow on March 15, 2022. Photo by MAXIM SHEMETOV/POOL/AFP via Getty Images.

6) In Israeli politics, one change led to another

Nimrod Goren

Senior Fellow for Israeli Affairs

Israel had a right-wing prime minister when 2022 began and will have a right-wing prime minister when the year ends. But what a difference those 12 months made. Three processes of change took place in Israel over the course of the year, each of which was of significant domestic and regional importance.

The first was the policy implemented during the first half of 2022 by the Bennett-Lapid government, the “government of change” as it was dubbed upon its establishment in mid-2021. This government, which included coalition partners from across the political spectrum (including an Arab party), effectively handled a variety of domestic issues, chief among them COVID-19, and made several foreign policy breakthroughs: mending ties with Jordan, normalizing relations with Turkey, reaching a maritime border deal with Lebanon, convening the Negev Summit and consolidating it into a formal forum, reconvening the Israel-EU Association Council after a decade, and advancing “minilateral” cooperation, some inter-regional in nature (e.g., I2U2).

However, while this process was taking place, another change was brewing. Right-wing opposition to the government was reaching new heights, populist and nationalist sentiments were rising and being mainstreamed, and personal rivalries within the centrist, leftist, and Arab parties were taking their toll. The government did not handle these successfully, the coalition collapsed, and the anti-Netanyahu bloc reached the November election fragmented — while Benjamin Netanyahu’s bloc remained unified. The results of the Nov. 1 vote were unprecedented, minimizing the parliamentary representation of the Israeli left, representing an all-time high for the far-right, and giving Netanyahu a comfortable majority for a coalition with his ultra-Orthodox and far-right partners.

The election results sparked a third process of change, which became increasingly vivid as coalition negotiations progressed. Its consequences, however, will become clear only next year. Israel is seemingly at a game-changing moment. The anticipated new government is not planning to merely walk back its predecessor’s policies, it aims to stake out transformative ideological ground. Its composition, internal division of labor, and declared policy intentions are already raising concerns about the future of Israel’s democracy, causing friction with its liberal-democratic global allies, and creating multiple sources of potential Jewish-Arab and Israeli-Palestinian tensions.

Escalation within Israel, between Israel and the Palestinians, and between Israel and the wider region are all becoming likely scenarios for 2023 and the international community will need to engage and take action in advance. This could include voicing clear messages about positions, expectations, and red lines; taking preventive diplomatic steps aimed at de-escalation, as was done successfully by Jordan’s King Abdullah before Ramadan this year; increasing support and backing to those in Israel working to advance peace and democracy; responding effectively to provocations on the ground; and promoting proactive regional initiatives to consolidate key bilateral relations, expand multilateral modalities, and generate tangible benefits from existing cooperation — all as potential safeguards against possible escalation.

PHOTO: Supporters of Israel's Likud party march with a poster depicting Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during an election campaign tour at Mahane Yehuda market in Jerusalem, on March 21, 2021. Photo by MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP via Getty Images.

7) Iraq ends its year-long political crisis, looks to improving regional relations

Randa Slim

Senior Fellow and Director of Conflict Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program

Last October, Abdul Latif Rashid was elected president of Iraq and, two weeks later, Mohammed Shia al-Sudani was named prime minister and sworn in along with a new cabinet. This marked the end of a year of political instability in the country following the October 2021 parliamentary elections. The Sadrists are neither represented in the current parliament nor in the cabinet, because of the decision by their leader, Shi’a cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, to withdraw from politics and force the members of his parliamentary bloc to give up their seats.

The new ministerial program prioritizes domestic matters, including job creation, improved public services, economic reforms, and the fight against corruption — all issues likely to bring Prime Minister Sudani into confrontation with his political allies in the Coordination Framework (CF) faction, who have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo that they believe would be threatened by structural reforms. Sudani’s top priority and main challenge will be to ensure a reliable supply of electricity next summer. Failing to do so would likely lead to a renewal of protests and calls for his cabinet’s resignation.

On foreign policy, the new Iraqi head of government has indicated that he will pursue a balanced policy, especially vis-à-vis the United States and Iran. He additionally wants to deepen ties with Arab countries, including members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as well as Jordan and Egypt, first and foremost in the economic and energy fields. Finally, he has pledged to pursue good relations with his immediate neighbors Iran and Turkey and to maintain Baghdad as a hub for Saudi-Iranian dialogue.

Sudani and many of his CF allies have indicated that they support the United State’s “advise, assist, and enable” military mission, fully aware that Iraq still needs U.S. assistance in its fight against remaining ISIS pockets. They also endorsed a similar position vis-à-vis the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) long-term capacity-building mission toward Baghdad.

Unlike his predecessor, Prime Minister Sudani will have a less tense relationship with Iran given the fact that he and his governing allies are viewed positively in Tehran. Arab governments, especially in the GCC, on the other hand, remain suspicious of a CF-supported government in Baghdad. It is up to Sudani to prove to them that he is his own man and not necessarily just “a manager,” as some of his CF allies claim.

There is an ongoing dialogue between Baghdad and Erbil to address their disputes over the budget and a new oil and natural gas law. The latter has been the subject of decade-long discussions between the two parties. A complicating factor in this dialogue is the ongoing intra-Kurdish dispute between the rival Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) over allocation of oil resources within the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). This dispute is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon primarily due to the lack of an acceptable mediator to both parties.

Political developments in Turkey and Iran have and will continue to cast a long shadow on the political and security situation in Iraq. Both neighboring countries have been targeting Kurdish opposition groups based in the KRI with drones and missiles. And Tehran has even threatened a ground incursion of the KRI. The Islamic Republic blames Iranian Kurdish opposition groups, including ones having found asylum in the KRI 15 years ago, of lending support to the protest movement that exploded last September. Turkey, in turn, blames KRI-based Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants of conducting terrorist activities against Turkish territory and for supporting Syrian Kurdish opposition groups. The leaderships in both Iran and Turkey have been using these attacks to deflect attention away from domestic grievances. Polls show that large swathes of Iraqis chafe at their country’s sovereignty being routinely disregarded by their neighbors. Both Iran and Turkey will, thus, find mounting limits to their ability to influence the situation inside Iraq, primarily because the latter country’s domestic political dynamics increasingly reflect public opinion.

Sadr, the influential Shi’a cleric and factional leader, has been silent to date. There are rumors that some members in his party are disillusioned with the decisions he has made, particularly the Sadrist parliamentary bloc’s resignation, and might be splitting away from his movement to form their own party. So far, most Iraqis want to give Sudani and his cabinet a chance to deliver on their promises. However, Iraqis are an impatient lot. The prime minister’s grace period is not going to last long. And Sadr will be waiting for the government’s first mistake to make his move against Sudani and his CF allies.

Follow on Twitter: @rmslim

PHOTO: Supporters of Iraq's Coordination Framework lift placards depicting the head of the Supreme Judicial Council Faeq Zaidan (L) and top Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, during a rally outside the capital Baghdad's high-security Green Zone, on August 12, 2022. Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images.

8) The impact of the rise of a new youth generation

Hafsa Halawa

Non-Resident Scholar

Since 2011, the leaders and regimes of the Middle East have had to contend with a globally connected, more widely educated, and increasingly independent thinking generation of youth. Whether it be the “millennial” uprisings of 2011, or the protests spreading once more in 2021 and 2022, led by the younger “Gen Z,” the region has failed to respond to demands of its younger populations. This has left younger Middle Easterners more frustrated, angrier, and readier to reject the parameters of incremental change, growing more vocally towards complete upheaval and regime change, even with the failed uprisings of 2011 behind them.

Of late, this dynamic is clearest in the protests sweeping across Iran, following the death of Masha Amini, the young Kurdish-Iranian woman killed by police after her detention for failing to wear her hijab adequately. The movement is being led fervently by young Iranians who have emphatically called for the end of the Islamic Republic. But it is also evident in the enduring nature of Sudan’s protests and its young and diverse civilian political movement, which continues to build and grow, more than a year on from the military’s coup in October 2021 that halted the democratic transition.

For years, the policy community in the region and beyond has closely analyzed, documented, and created policy prescriptions based on the challenges for regimes — led generally by septuagenarians or octogenarians — of responding to their growing, more youthful populations. In countries that continue to crack down through authoritarian practices, the inability to track, follow, and effectively silence movement-building efforts online, notably through social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter, has resulted in change that might be deemed incremental in the long arc towards democratization, but is nevertheless fundamental. This is evident in the whirlwind transformation taking place in the Gulf, where younger leaders are accelerating change. Saudi Arabia is opening up its formerly religiously protected society to embrace youth culture and Western arts, while Qatar is hosting the region’s first World Cup, embracing citizens from all over the world and opening itself up to difficult conversations about its treatment of migrant workers (through the kafala system), women, and the LGBTQ community.

But the impact of young people on regimes and social cohesion in the region is also evident in some of the more stagnant and stable regimes, including Egypt, where an active and exciting feminist movement is rebuilding itself, led primarily by young, teenage Egyptian women who are changing the conversations on sexual assault, violence, consent, and pleasure.

And for the Palestinians, the collision of all of these new forms of movement building and advocacy, alongside new avenues for expression, has reinvigorated a Middle Eastern movement of solidarity with the Palestinian people. With the new face of Palestine more commonly becoming those of activists Mohamed al-Kurd, Lina Abu Akleh, or Muhammad Shehada, their advocacy methods are also having a political impact that extends well beyond merely reviving the cause for statehood. Within the Occupied Territories, advocates and activists have moved past global diplomacy to force a reckoning on the decades-long conflict. Their language, messaging, and online activism targets accountability from the Israeli state for crimes committed against the Palestinian people, instinctively moving beyond the two-state debate to embrace — at least legally — the principles of one state and the pressure of accountability that falls squarely on Israel’s shoulders. As activists on the ground shape a new iteration of the Palestinian movement, the plight of its people has once again taken center stage across the region. While the focus in recent weeks has been on the very public show of solidarity at the Qatar World Cup among Middle Eastern football fans, such support does not go ignored back home, impacting the decision-making of leaders even as they forge ahead with normalization agreements with Israel.

These new forms of advocacy — using traditional methods or new and innovative ways to organize and build movements — are creating a more durable critical mass of citizens seeking change that is harder for the region’s authoritarian leaders to suppress. The result is more pragmatic policies, in some cases limited concessions, and clear-eyed decisions made with the people in mind. While little appears to be changing when it comes to democratic principles, young people have brought citizens the power of, once more, being part of the political calculation of leaders.

Follow on Twitter: @HafsaHalawa

PHOTO: Women protest over the death of 22-year-old Iranian Mahsa Amini in front of the Iranian Consulate on September 26, 2022 in Istanbul, Turkey. Photo by Ozan Guzelce/ dia images via Getty Images.

9) A year of extreme climate impacts puts pressure on climate policy to deliver

Mohammed Mahmoud

Senior Fellow and Director of the Climate and Water Program

Following several missed opportunities to move global climate policy toward a more climate-resilient future — including the lackluster outcome of the watered-down Glasgow Climate Pact at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (26th Conference of the Parties, COP26) and the United Nations Security Council veto on recognizing climate change as a security threat — 2022 brought about a suite of climate change impacts that were even more extreme than what was experienced in 2021, particularly for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

MENA’s climate is already prone to keeping the region hot and dry, but the amplification of aridity and drought conditions in the late spring and early summer of 2022 triggered a series of severe dust storms that blanketed most of the Arabian Peninsula and beyond, with serious implications for public health.

The effects of climate change on summer 2022 also manifested in record-breaking heatwaves across Europe, Asia, North America, and MENA. Besides the higher incidence of heat-related illnesses, the dangerously high temperatures corresponding with these heatwaves also elevated the risk of wildfires (especially around the Mediterranean).

The culmination of this summer season also saw an uptick of heavy precipitation and flooding events due to the extended warming of the Indian Ocean. The southern Arabian Peninsula experienced some of this greater-than-average rainfall, but Pakistan suffered the worst of it. An amplified monsoon season proved devastating to Pakistan (and to a lesser extent Afghanistan) with extensive and significant flooding, damage, and loss of life.

The cumulative effect of all of these climate impacts placed renewed pressure on developed nations to make more impactful strides in pushing the global climate agenda forward in terms of climate mitigation and adaptation. This made the focus on COP27, hosted by Egypt, more acute, with expectations for the meeting to make more meaningful progress than COP26 did. The extreme climate events of 2022 (and the inadequacy of current global emissions reduction plans to limit dangerous increases in future global warming) proved to be the catalysts needed for developing and climate-vulnerable nations to seek more aggressive action on climate mitigation, adaptation, and justice. While efforts to curb carbon emissions and expand financing for adaptation efforts at the meeting were not substantial, negotiations at COP27 delivered a huge victory for developing nations that have suffered the worst consequences of climate change while contributing the least toward it in terms of emissions: agreement on the development of a climate “loss and damage” fund. This agreement now serves as the first major step toward attaining climate justice and compensation for those nations that have historically been most adversely affected by climate change.

PHOTO: Conference participants walk through an illuminated tunnel at the UNFCCC COP27 climate conference on November 08, 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images.

10) Egypt exemplifies MENA region’s dramatic human security challenges

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

A short, solid line connects economic security and stability in most economies. That statement is doubly true for the majority of countries in the Middle East and Africa; governments deliver economic security and, in return, their citizens provide a measure of political acquiescence. The year 2021 was a bad one for regional governments attempting to walk that line: the COVID-19 pandemic played havoc with economies, and rumbling regional discord occasionally spilled over into actual coups and civil wars. When the ravages of the pandemic started to die down by the end of the year, there were collective sighs of relief and a nascent hope that in 2022, perhaps things could start getting back to “normal” and governments could begin patching the cracks in their economies.

It was not to be. In late February, Russia invaded Ukraine, blighting the global economy with food and energy shortages and severe supply chain disruptions, affecting various economies in different ways. In Egypt, the MENA region’s most populous nation, the effects were felt almost immediately. The country is the world’s largest grain importer, and approximately 80% of that grain comes from Russia and Ukraine. Those imports go toward state-supplied bread, which helps make the difference between subsistence and hunger for approximately 30% of the population. Heavily subsidized bread is inextricably linked to Egypt’s stability. As such, not only did this subsidy survive the sweeping economic reforms of 2016 but, in fact, the price of state-supplied bread (as opposed to that sold by private bakers) has not changed in over 35 years. In an effort to protect itself against internal economic turmoil, Egypt stockpiled grain supplies; but this was only ever a temporary hedge. Cairo had to struggle to find grain to feed its poor and, worse, had to shell out more of its dwindling foreign currency supplies to do so. Slowly but surely, the global downturn placed pressure on the straining seams of Egypt’s economy, exposing key structural weaknesses. Those weaknesses might have been disguised or overcome under normal circumstances, but 2022 brought to life every economist’s worst fear.

In an effort to boost growth, Egypt had for years spent heavily on public infrastructure; those projects provided employment in the short run and are intended to boost investment, but they also helped siphon foreign currency. Again, that might have been manageable if the global economic downturn hadn’t resulted in foreign investors behaving precisely to type: swiftly pulling their funds out of developing economies and re-investing in developed ones seen as safer. The situation became so dire earlier this year that Minister of Finance Mohamed Maait publicly declared that “Egypt could no longer rely on hot money,” noting that in four years, he’d had to manage three shocks to the economy as a result of this type of capital flight. In the first quarter of 2022 alone, Egypt lost around $20 billion in fleeing capital. Meanwhile, Egypt still had to pay out hard currency for its imports while struggling with rising external debt.

In March, Egypt began negotiating with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a new loan, which was finally announced almost nine months later: $3 billion under the Extended Fund Facility and another $1 billion under the Resilience and Sustainability Trust. That loan, however, was conditioned on three points: shrinking the country’s deficit gap, maintaining a flexible exchange rate, and opening up the country’s investment climate, generally understood to be a pointed commentary on the outsize role of the state in the economy. Egypt promptly devalued its currency, by 14.5% on Oct. 27, but it has since dipped even more sharply against the dollar, with serious consequences. The drastic shortage of foreign currency led to food and fodder imports being held up at the ports, further driving up prices of vital goods at home. The black market, for years dormant, reemerged and is currently trading at 30-32 Egyptian pounds against the U.S. dollar, fueling currency hoarding and driving up gold prices. Egypt’s non-oil sector has been contracting for nearly two full years, recently seeing its sharpest decline in almost two and a half years. The government has attempted to shield its citizens from the fallout, raising pensions and minimum wages and extending social safety networks like cash transfer programs. The hope is that the economy will weather this crunch the way that it did the 2016 devaluation, buoyed by an expected return of foreign direct investment.

Nor is the economy the only dark cloud on the horizon. Egypt, along with the rest of the region, is under severe threat from climate change. MENA is the most water stressed region in the world. Rainfall is projected to decline by 20-40% if average global temperatures rise by 2 degrees, an especially grim projection when one considers that almost 70% of the region’s agriculture is rain-fed. Africa, which contributes less than 3% to global greenhouse gas emissions, will suffer the most, seeing escalating water stress and hazards like droughts and devastating floods, all the while coping with rising populations. Rainfall patterns are being disrupted, lakes are drying up, and glaciers are disappearing, according to a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

There are, however, potential bright spots. While the world struggles with the fallout from fossil fuels, MENA countries have some of the highest wind and solar energy potentials in the world. Over 40 African countries have revised their national climate plans (Nationally Determined Contributions), making them more ambitious and competitive, while increasing commitments to climate adaptation and mitigation. And if last month’s COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, helped showcase anything, it was young, engaged, ambitious people keen on forging their own futures.

The only advantage to a really bad year is that it’s easier to hopefully do better the following one.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

PHOTO: A boy buys bread at a market in Cairo, Egypt, on March 9, 2022. Photo by Ahmed Gomaa/Xinhua via Getty Images.

TOP PHOTO: The Middle East and Europe are seen upside down on the public art sculpture The World Turned Upside Down by artist Mark Wallinger on 6th December 2022 in London, United Kingdom. Photo by Mike Kemp/In Pictures via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.